In the theatre gardens in Stratford-upon-Avon is a silver birch tree planted in memory of Vivien Leigh, one of several dedicated to people who have worked at the theatres. At its base is a stone tablet, with her dates of birth and death (1913-1967) and the Shakespearean phrase “a lass unparalleled”. Over Christmas somebody has placed an artificial red poinsettia there, and it’s lovely that somebody still remembers her stage career.

Vivien Leigh became an international star in 1939 with the film of Gone With the Wind for which she was awarded the Oscar for Best Actress. She and Olivier married the year after. They became the most famous acting couple of the era, and for many it was Leigh who was the bigger attraction.

She appeared in Stratford for just one season, in 1955 when she played a varied threesome: Viola in John Gielgud’s production of Twelfth Night, Lady Macbeth in a production directed by Glen Byam Shaw, and Lavinia in Peter Brook’s Titus Andronicus. Olivier too was in all three: playing Malvolio, Macbeth and Titus.

It was by far the biggest theatrical event in its history: the couple were like royalty, and Leigh’s cocktail parties became legendary. According to Sally Beauman’s book on the RSC “The box-office was immediately besieged for tickets: 500,000 applications arrived for the 80,000 seats available in the opening weeks of the season.” Neither actor had recently played in Shakespeare, but they had worked together in Antony and Cleopatra in London and New York during the Festival of Britain year, 1951. Here is a short sound recording from this production.

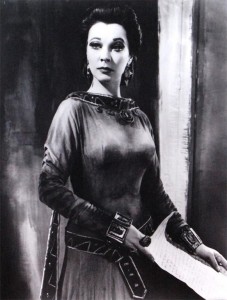

The season was a guaranteed commercial success, but critically it would have been difficult to be anything other than an anti-climax after the amazing pre-publicity. The season opened with Twelfth Night, by most accounts somewhat disappointingly. Macbeth, the third of the five plays in the season, was the one everybody was really waiting for, a chance to see this famous pair playing as a couple. Olivier had already played Macbeth at the Old Vic in the 1930s. His masterful performance this time dominated the play and the reviews, but in the photographs, it’s Leigh who draws the eye. Her costumes were created by leading designers, in particular the figure-hugging green dress she wore as Lady Macbeth, and her great friend, the photographer Angus McBean brought all his skills to bear.

The final play in the season was maverick director Peter Brook’s production of Titus Andronicus. It was the first time this unplayable play had been performed in Stratford. Some years earlier a production in London had been greeted with laughter. Brook spent months preparing for the production, taking total control over the set and costume design, and the music, as well as directing. Sally Beauman again: “With every means at his disposal Brook played on the nerve-endings of his audience, but he played subtly;…there was no visible gore; when Lavinia’s hands had been chopped off she came on to harp music, her wrists spouting not blood but long red velvet ribbons…certainly audiences did not laugh, though many among them fainted.” All the critics wrote about Olivier, ignoring the fact that Lavinia is an impossibly difficult part, having to express the agony of her situation with no words, and no hands.

In other places Leigh had successfully played complex roles: Scarlett O’Hara, Cleopatra, Blanche DuBois (for which she won another Oscar). Suffering from recurrent bouts of tuberculosis, as well as a variety of mental illness that made her appear unreliable and difficult, and her marriage in trouble, Stratford probably did not see the best of Vivien Leigh.

Director George Cukor called her “a consummate actress, hampered by beauty”, and many people commented on the difficulty she had in being taken seriously. She was known to work ferociously hard. Gielgud suggested her problem was “timidity”, “she hardly dares at all and is terrified of overreaching her technique and doing anything that she has not killed the spontaneity of by overpractice”. Influential theatre critic Ken Tynan’s belittling of her, while consistently praising Olivier, was very damaging to her confidence. It was only after her death that he admitted he had been wrong, particularly about her Lady Macbeth.

In 2013 her personal archive was sold to the Victoria and Albert Museum. It contains thousands of items including diaries and scrapbooks. The British Library also contains many of her letters within the Laurence Olivier archive. Work on these archives is already allowing new assessments to be made of this glamorous but troubled woman. On 9 February one such event is to be held: a lecture is to be given by the University of Exeter’s Dr Lisa Stead, at Henley Business School, entitled ‘Vivien Leigh as Creative Labourer: Archives, Gender and Visibility’. For anyone wanting to know more about Vivien Leigh, Kendra Bean’s site is a treasure-trove.

The phrase on the stone comes from the very end of Antony and Cleopatra, when Charmian describes her dead mistress. The lines are appropriate:

Now boast thee, death, in thy possession lies

A lass unparallel’d. Downy windows, close;

And golden Phoebus never be beheld

Of eyes again so royal!

Update: on 29 January 2015 it was announced that the catalogue of the Vivien Leigh Archive is now available online. Here’s the link: http://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/theatre-and-performance-2/the-vivien-leigh-archive

I think that Vivien Leigh was the greatest actress tying WITH ELIZABETH TAYLOR. I would have given anything to see her perform on THE stage.

Thanks for your comment Sarah. They were both very compelling actresses, though quite different!