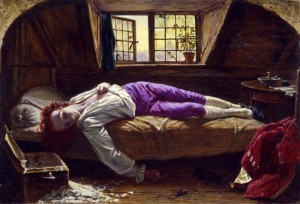

Henry Wallis isn’t one of the best-known of the Pre-Raphaelite painters, barely getting a mention in books about Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Millais, Holman Hunt et al, but one of his paintings is universally-known and classed as a masterpiece. The Death of Chatterton was painted in 1855-6 and represents the suicide by poisoning of the 17-year old promising poet in 1770. The painting is full of immaculately-painted detail of not just the man but the dingy room in which he is imagined to have died. Poets such as Shelley, Wordsworth and Coleridge helped to secure Chatterton’s reputation, and the poet George Meredith modelled for Wallis’s painting.

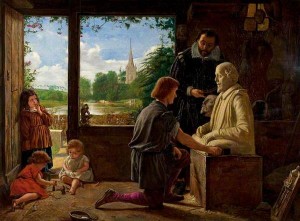

Henry Wallis (1830-1916) was an elusive figure, but the BBC Your Paintings website brings together several of his paintings. I was already familiar with the one owned by the RSC: A Sculptor’s Workshop in Stratford-upon-Avon, 1617. It’s painted with the same attention to detail, but it’s an even more imaginative, fanciful composition. It was painted in 1857, and plays with the idea of the creation of Shakespeare’s memorial bust. The sculptor kneels in front of it while Ben Jonson holds the so-called Kesselstadt death mask which had been discovered in Mainz in 1849. Has the sculptor has got Shakespeare’s features wrong? Through the window of the workshop the River Avon and Holy Trinity Church are visible: the view can still to be seen from the Theatre Gardens today. I’ve always liked the way it asks a question about the authenticity of the many Shakespeare portraits and perhaps suggests that Shakespeare’s appearance isn’t really what matters.

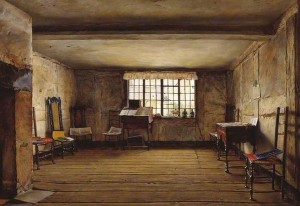

This isn’t the only painting by Wallis with a Shakespeare theme. He obviously visited Stratford around 1853 when he had just completed his studies in Paris. Two more of the pictures he worked on in Stratford are on the BBC Your Paintings site. The Room in which Shakespeare was Born is astonishingly realistic, its details confirmed by other images that show some of the same furniture and the frilly pelmet over the window. This blog post, from Tate Britain where the painting is kept, comments that you can see every nail in the bare wooden floor. Like the painting of Chatterton, the room is lifeless and dingy, and on the same visit Wallis also painted The Font in which Shakespeare was Christened. Although I have not tracked this down, it seems that this too depicts a place empty of the genius which once inhabited it.

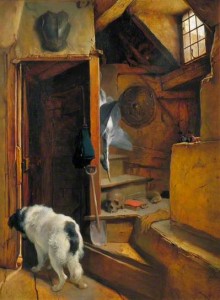

Painted at around the same time is Shakespeare’s House, Stratford-upon-Avon. This is now at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and shows a corner of the house with a wooden staircase leading upstairs. Unlike the painting of the Birthroom, though, this one includes a number of symbolic objects: a skull and spade representing Hamlet, a book, a glove (a reminder of the profession of Shakespeare’s father), a shield and breastplate perhaps representing Macbeth. Most noticeable though is a dog, on the alert for his master approaching the other side of the door.

The painting is well-documented. It belonged to John Forster, chairman of the London committee of the Royal Shakespearian Club and friend of Charles Dickens. He helped to secure the Birthplace for the nation in 1847 and visited the house several times. Correspondence reveals that the painting was changed by Sir Edwin Landseer. This is an extract of Forster’s letter to Landseer, reproduced when the painting was exhibited in 1867:

The picture in its first state – then an ancient stone staircase wonderfully painted by Mr H Wallis, the painter subsequently of the Death of Chatterton, – was purchased by me fourteen or fifteen years ago. You had often said, as you saw it in my dining-room, that you’d like some day to put something from your own hand into it; and last summer, generously indulging my earnest wish to possess some memorial of our thirty years of uninterrupted friendship, you desired me to send this particular picture to you. That the staircase as represented had been copied from Shakespeare’s House at Stratford-on-Avon, you did not then know, or had forgotten… Finding, when the picture reached you, whose house it was the staircase belonged to, it had been your fancy to bring about us memorials of the marvellous man himself, – his dog waiting for him at the door, as to imply his own immediate neighbourhood; and objects so connecting themselves with his pursuits, and even pointing at the origin of familiar lines and fancies, as almost to indicate and identify the Play with which his brain might have been busy at the time.”

Landseer’s additions apart, the painting is interesting as it shows a quiet corner of the building in the period between its purchase for the nation in 1847 and its restoration about 10 years later. The house had been neglected and the work, based on a careful survey in 1857, intended “to remove with a careful hand all those excrescences which are decidedly the result of modern innovation, to uphold with jealous care all that now exists of undoubted antiquity, not to destroy any portion about whose character the slightest doubt does now exist”. Landseer’s additions may not have contributed to the accuracy of the painting, but like Forster I agree that Landseer breathed spirited life into Wallis’s representation of this “cradle of genius”.