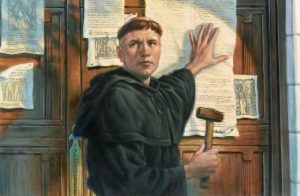

It’s one of the most famous of images: a simply dressed monk takes a hammer and nails, the symbols of the crucifixion of Christ, and fixes a large document to the wooden door of a church. The date was 31 October 1517, the monk was Martin Luther, and the document was his Ninety-five Theses or Disputation on the Power of Indulgences. The story goes that this act of revolutionary defiance began what came to be known as the Reformation when the Roman Catholic Church in Europe began to break up. Luther fixed his sights on the corruption of the overwhelmingly powerful Church, instead preaching the importance of individual faith and responsibility.

Like most of the best stories, though, it’s not true. On 31 October 1517 Luther took the much less public course of writing to Albert of Brandenburg, the Archbishop of Mainz, hoping to provoke a discussion about reforming the Church from the inside. If the rather academic document was ever nailed to the church door this happened later, but came to be seen as a symbol for what followed. The now-common pictures of Luther and his document only became popular in the nineteenth century. This post from The many-headed monster blog records that the Protestant Martyr’s Memorial in Exeter includes a bronze panel showing “Exeter’s Luther”, Thomas Benet, affixing papers to the door of the city’s Cathedral, an event which actually did happen. Benet, inspired by Luther, wrote his own thoughts about Church corruption, for which he was condemned for heresy and executed in 1532. It took until 1909 for this monument to be erected. A more recent copying of this symbolic gesture took place in 1966 when Martin Luther King nailed a set of demands for racial justice to the door of Chicago’s City Hall. Peter Marshall has written a fascinating piece on the history of this symbol here.

What, though, did Luther have to do with Shakespeare? In England the Reformation was adopted only in the reign of Henry VIII, when the Pope refused to annul his marriage. In 1534 Henry declared himself the head of the Church in England and dissolved the monasteries, confiscating their wealth. The ruins of places like Tintern Abbey are melancholy and picturesque, but it’s hard now to imagine how great the impact of their closing must have been. Religious establishments had a strong social function in addition to their overwhelming spiritual importance.

Across the country change took decades. Stratford-upon-Avon’s Guild of the Holy Cross was abolished, its governmental responsibilities taken on by a new Borough Council in 1553, and the school was refounded. Shakespeare’s father John was among the first to become involved in this new Establishment, rising to become one of the principal burgesses and bailiff. The Council oversaw changes to the Guild Chapel, protestantizing it by whitewashing the frescoes. This removal of decoration in churches was supposed to do away with superstition and the worship of idolatrous images, but also symbolically signalled a new order.

Shakespeare’s parents lived through some of the worst upheavals, but even under the relative stability of Queen Elizabeth’s long reign England was still a dangerous and uncertain place. When he came to write his own plays, Shakespeare knew it paid to tread carefully, especially when it came to telling a version of a true story. In his only play that deals with the period of the Reformation, Henry VIII, no blame attaches to the King. Rather than discussing religious dogma the play is mostly a series of personal tragedies. Cardinal Wolsey, disliked by all for his arrogance and power, is brought down by greed and his underhand communications with the Pope. He intended to prevent Henry from marrying Anne Boleyn, “A spleeny Lutheran”, destined to be the mother of Queen Elizabeth. Here Archbishop Gardiner warns of the strife that could erupt in England as in Saxony following the religious upheavals there:

Commotions, uproars, with a general taint

Of the whole state, as of late days our neighbours,

The upper Germany, can dearly witness,

Yet freshly pitied in our memories.

This weekend, on 3 and 4 November 2017, a two-day conference is taking place at the National Archives in Kew focusing on research into the Reformation that has been carried out using records from the National Archives themselves. Entitled “Reformation on the Record” it will feature more than 30 speakers from academic institutions across the UK and to quote their publicity “It is our intention to create a network of scholars and postgraduates researching the Reformation using our documents, and to develop the profile of The National Archives as a hub for Reformation studies.” A Facebook research group has already been set up and there are some great educational resources in place.