Projects involving Shakespeare have, as ever, been coming thick and fast over the last couple of months. There are a tremendous variety of books, websites, and films (some still requiring help to get made).

Projects involving Shakespeare have, as ever, been coming thick and fast over the last couple of months. There are a tremendous variety of books, websites, and films (some still requiring help to get made).

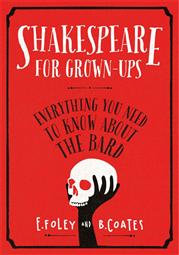

First up is a book I’ve really enjoyed exploring, E Foley and B Coates’ book Shakespeare for Grown-ups: Everything you need to know about the Bard. The style is approachable and fun without being patronising and it’s well-designed, with illustrations that are useful rather than glossy. Each play is summarised in a single sentence, no mean feat in itself, and the most popular get a section to themselves that includes Key Themes (for The Tempest these are Power, the Supernatural and Colonisation), and Key symbols to look out for (the Moon in A Midsummer Night’s Dream). There is information about other artists’ responses to The Tempest, lists of doomed lovers in the Romeo and Juliet chapter, and references to Shakespeare’s anachronisms in that for Antony and Cleopatra. With sections on Shakespeare’s most redoubtable women and Shakespeare’s best minor characters it’s the sort of book I can imagine dipping into time and again. All the basics are here too: a chapter on Shakespeare’s life, another on his language, and one on the poems. Further fascinating facts for the Shakespeare fan is just what it says, with information about collaboration, a suggested chronology for the plays, some great quotes arranged by subject, and a Shakespearian quiz. And, heavens be praised, there is a really full index. I don’t know quite how they’ve managed to cram so much great stuff into just over 300 pages, but I would say well done!

The next one is a book I haven’t actually seen, but one that sounds both inspiring and entertaining. From the publisher’s blurb:

The next one is a book I haven’t actually seen, but one that sounds both inspiring and entertaining. From the publisher’s blurb:

“Teaching Will: What Shakespeare and 10 Kids Gave Me That Hollywood Couldn’t is about struggling actress Mel Ryane’s work to introduce the Bard to an underserved Los Angeles public elementary school. Every week Mel encounters unexpected comedy and drama as she and the children struggle toward staging a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

In the schoolyard, Mel finds herself embroiled in jealousy and betrayal worthy of Shakespeare’s plots. Fits of laughter alternate with wiping noses as she and the kids discover a surprising truth: they need each other if they want to face an audience and triumph. Teaching Will is an uplifting story of empowerment for dreamers and realists alike.”

Now on to some versions of Shakespeare’s plays:

Rob Myles has created a video that looks at the wooing of Katharina in a fresh way. His short film is entitled Katharina the Curst: “Our mission was ‘Reinventing Shakespeare’, so we retold Taming of The Shrew as a historical action romantic comedy set in Viking-era York.

Paradoxically, taking the story further back in time allowed us to reposition Katharina in a manner more palatable to modern audiences. In a time when Viking women could own property, divorce husbands and go into battle, such a life would seem hugely appealing to a Katharina raised in the Christian culture of the time. ”

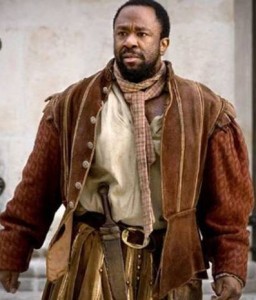

This next one is a feature film looking for funding, with a Kickstarter campaign in full swing. It’s being run an American filmmaker, Devin E Haqq. Based on Julius Caesar, it will be called Ambition’s Debt, to be filmed in New York and set in a post-apocalyptic world. Here is Devin’s description of what he hopes to achieve:

“I want to change the face of what Shakespeare is “supposed” to look like by telling this story in a way that’s fresh and relevant and captures the diversity of our unique democratic society. My hope is, that by bringing Shakespeare’s words into this modern context, we will…encourage young audiences to think critically about the society in which they live.”

There’s more information on the Kickstarter page: if you want to help him make the film, you can make a donation there.

Back in London, a new novel by a German author called Root Leeb is just about to be published, entitled Hero. It’s the story of a dying man and his relationships with his children, The publishers describe how

Back in London, a new novel by a German author called Root Leeb is just about to be published, entitled Hero. It’s the story of a dying man and his relationships with his children, The publishers describe how

“Leeb draws on the father-daughter constellation of King Lear in a family with many different parent-child relationships which makes for a very interesting story of not only family dynamics, but also how the patriarch of this family takes an eye-to-eye approach to his own death.”

Ready Set Go Theatre Company from New York are presenting Romeo and Juliet “through a unique 10 episode web series”. All episodes are available at the website above. It’s described as a “gritty,daring adaption” set in New York City, adapted for screen by John Robert Hurley, it’s their second Shakespeare web series. In order to “make the classics available to a new generation of theatre and film enthusiasts, …focused on making Shakespeare a vital part of the modern classroom. R & J (the web series) will have lesson plans included for every episode, and teachers will have all the information available for free when they contact RSG.” A trailer is available.

For an unusual take on Hamlet, Darrien Murphy is producing a film Hamlet’s Mouse-trap. Here is his description:

“The film was inspired by Hamlet, (hence the name) and is written in the Shakespearean tradition. “Hamlet’s Mouse-trap” is about a contemporary Romanov descendant who, consumed by grief over the murder of her mother, sets out to discover the perpetrators who killed her, whilst also experiencing a spiritual struggle about the costs of what she seeks.”

Finally, Juliet’s Nurse, by Lois Leveen. “It’s a novel imagining the 14 years leading up to the events in Romeo and Juliet, from the point-of-view of that unforgettably ribald/comic/tragic character, Angelica.” Leveen “writes literary historical fiction as a way to “teach” readers beyond academia; this novel draws on research in medieval and Renaissance Italian history, as well as Shakespeare’s play… it’s intended for general audiences who will be drawn in by the characters and story line (and hopefully go back to read the play once they are done with the novel).”

Finally, Juliet’s Nurse, by Lois Leveen. “It’s a novel imagining the 14 years leading up to the events in Romeo and Juliet, from the point-of-view of that unforgettably ribald/comic/tragic character, Angelica.” Leveen “writes literary historical fiction as a way to “teach” readers beyond academia; this novel draws on research in medieval and Renaissance Italian history, as well as Shakespeare’s play… it’s intended for general audiences who will be drawn in by the characters and story line (and hopefully go back to read the play once they are done with the novel).”

I hope you enjoy exploring just some of these great Shakespeare-related projects coming our way!