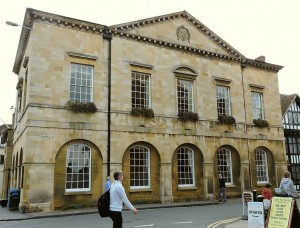

Standing at the busy junction of Sheep Street, Chapel Street, Ely Street and High Street is Stratford’s Town Hall. From the outside it’s a dignified building built of Cotswold stone and facing towards the High Street, in a niche, is the statue of Shakespeare that was presented by David Garrick at the time of his Jubilee in September 1769.

There has been a Town Hall on this spot since 1633. The original building consisted of a covered market area at ground level with a room above that could be used for functions. In 1642 it was being used as a munitions store by Parliamentary forces when it exploded. It was repaired in 1661 but was mostly neglected and by 1767 it was “in a dangerous and ruinous state”, and a decision was made to rebuild it, re-using as much of the original material as possible.

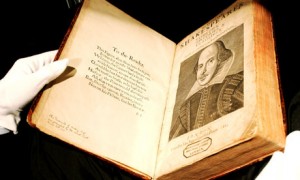

This first building had the distinction of being the venue for the first recorded performance of a Shakespeare play in Stratford when on Tuesday 9 September 1746 John Ward’s touring company performed Othello, in aid of the bust of Shakespeare in the church which was “through length of years and other accidents become much impair’d and decay’d” “The receipts arising from which Representation were to be solely appropriated to the repairing the Original Monument aforesaid”. In the sole surviving playbill for this historic performance the words “in the Town Hall” have been added by hand.

The new building followed the plan of the first, but it was to be built in finer fashion. The idea of inviting a David Garrick to contribute came from lawyer Francis Wheler, “in order to flatter Mr Garrick into some such hansom present… it wou’d not be at all amiss if the Corporation were to propose to make Mr Garrick an Honourary Burgess of Stratford”. From this suggestion came the three-day Garrick Jubilee though the Town Hall, the starting point for the festivities, was hardly used apart from public breakfasts on each day. The statue of Shakespeare remained in the specially-built pavilion and was hoisted into position at some point later, though there is no record of this. The final event of the Jubilee, a ball, did occur in the Town Hall, when the highlight of the evening was the dancing of Garrick’s wife.

The decoration of the hall was remarked on: “neatly and magnificently decorated with Festoons and Ornaments in Stucco, with the Harp string etc very curiously expressed in Basso-Relievo”. Within the hall were several paintings including Gainsborough’s portrait of Garrick, one arm nonchalantly draped round a pillar on which stood a head-and-shoulders statue of Shakespeare.

After the Garrick Jubilee the Hall was used for many regular social functions. For many years it was referred to as Shakespeare’s Hall, a reminder of Garrick’s grand Jubilee. After the formation of the Shakespeare Club at the Falcon Inn in 1824 it was only two years before they needed to move to the Town Hall for their annual dinner, which 225 gentlemen attended. These were boozy affairs with dozens of toasts, speeches and songs being sung. The dinner continued to be held on Shakespeare’s birthday until 1879 when the evening began to be marked by a performance at the new Memorial Theatre.

Over the years alterations became necessary. Social events such as hunt balls were becoming more elaborate, and magnificent celebrations were being planned for the 1864 Shakespeare tercentenary which included events at the Town Hall. There was no plan to alter the upper room “said to be the finest in Warwickshire”. With the open area on the ground floor not really needed as a market the answer was obvious. This area was enclosed, and a new entrance and grand staircase was built.

From 1868 the Town Council moved its meetings into the newly-created rooms on the ground floor, and at the same time the boards giving the names of mayors and town clerks which are still a major feature were created.

In the twentieth century the upper room was also used for the Birthday luncheon attended by diplomats and other representatives of national and international organisations, until it outgrew the space. The Hall continued to be the venue for a variety of local activities, including dances. It was after one of these in December 1946 that a fire broke out in the room. Many items relating to the traditions of the Town Council were saved, but the upper floor was gutted and the roof collapsed. The painting of Garrick was destroyed. Ironically it had only been put back a year before after being removed for safety during the war.

Huge efforts were made to rebuild the Town Hall, making it even better than before. The chandeliers were replaced and it was possible to cast new plaster sconces from the one which survived the fire. These were some of the room’s most attractive decorative features (they can be seen between the windows), and the opportunity was taken to include a different face on each one. Not surprisingly both Shakespeare and Garrick were chosen.

The Town Hall is not regularly open to the public, but the rooms are increasingly being used for events. They don’t allow 226 people to dine there nowadays, but I was lucky enough to attend a dinner there earlier this year that gave me time to reflect on the Shakespeare Club meetings and dinners, and even performances of Shakespeare’s plays, that have been held in this historic spot.

I’m indebted for many of the details in this post to Mairi Macdonald’s pamphlet The Town Hall, Stratford-upon-Avon, published by the Stratford-upon-Avon Society in 1986.

There is more information about the Town Hall on the Town Council’s website.