Recently the Huffington Post published an article written by a teenager about how Shakespeare should be taught, specifically to ten-year olds. She remembered her own experience “when I moved up to secondary school I was thrown into the deep end; baffled with sentences that didn’t make sense, characters who moaned endlessly at an empty, starless nights, and story lines that concluded with every character dying at the end.” At fourteen “the way I was introduced to Shakespeare was not dry, boring or strenuous; I was helped along the way using a variety of methods: from hands-on active engagement, to learning monologues off by heart.”

Alix Long, the author of the piece, goes on: “Maybe it is not the actual language in Shakespeare’s plays that makes it hard for children to be interested in the story. Perhaps it is the way that we teach Shakespeare that causes the confusion, the difficulty, the anxiety”.

She examines several approaches that can be seen to work. Brendan Kelso’s books Playing With Plays “aim to amuse, inspire and actively engage children and adults alike”, using humour, energetic language and some of Shakespeare’s original words. Ian Campbell, working at the Shakespeare by the Sea Festival in Canada put on a Shakespeare production specially for kids, for free, getting a terrific response from the children. And Debra Williamson takes Shakespeare back into the classroom, using resources that help introduce young children to Shakespeare. “I think your question to me really is the answer….you have to know your students, and within that group, find material that interests and engages them. My students loved choosing their own plays, creating their costumes, and feeling free…to showcase their … newfound love of Shakespeare.”

Enjoyment plus learning is always a successful combination. As Tranio suggests to his master in The Taming of the Shrew “No profit grows where is no pleasure ta’en:/ In brief, sir, study what you most affect”.

Alix Long concludes: “I think those words can speak for themselves. If only we can eradicate the idioms ‘hard’, ‘confusing’ and ‘difficult’ from the language of students studying Shakespeare, then we can really start to change the way Shakespeare is taught, appreciated and understood by children, teenagers and adults in schools and wider society.”

Now she’s not saying anything particularly new, but it’s interesting that a teenager is already concerned enough to try to find an answer to the issue of why Shakespeare, which seems to be appreciated so readily by children, is still so badly taught.

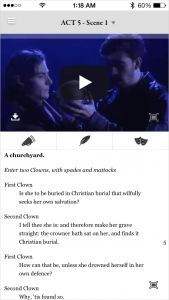

Even though she has probably been exposed to digital media from an early age, she does not consider any method of engaging with Shakespeare that uses computers, smartphones, digital cameras or tablets. I’ve just been sent details of an app, Shakespeare at Play, that aims to bring people Shakespeare’s plays as they are meant to be experienced. Through the app the user watches a video of every scene, staged simply, simultaneously reading the text. It’s a simple idea using technology to help those who struggle with the words alone, and there are sample on the website.

The newly published book Shakespeare and the Digital World is much concerned with education, whether it’s teachers and students, publication or theatre companies trying to engage with audiences. The section of the book looking specifically at education examines work being carried out at undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

The newly published book Shakespeare and the Digital World is much concerned with education, whether it’s teachers and students, publication or theatre companies trying to engage with audiences. The section of the book looking specifically at education examines work being carried out at undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

Sheila Cavanagh and Kevin Quarmby have undertaken a transatlantic experiment. “Captivated by the idea of offering students in…class the opportunity to offer practitioner-based text and theatre exercises through videoconferencing, these instructors set up jointly-led classroom sessions, with Quarmby interacting with Cavanagh’s…undergraduates from his office in London.” Students entered into a kind of rehearsal situation in which they work through a scene with Quarmby via Skype, with sometimes unexpected results.

Erin Sullivan writes about the attempts that have been made at the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford to “align” online teaching for distance learners with that for those actually there. “Some of the best things about our community are decidedly analogue – impromptu research conversations in the garden, weekly play-readings of lesser-known Renaissance plays and seminars on Shakespeare’s life and works”. Reading and lectures are easily adapted, but seminars are difficult to replicate. Written conversations have been tried, but without the unselfconscious spontaneity of a group discussion “there is more premeditation, planning and single-mindedness in their answers”.

This is no bad thing in itself: in his essay Pete Kirwan considers the value of blogging “as a means of enabling self-reflection, critical awareness and intellectual independence among students”. The solitary activity of blogging, then, has its place, but is only one element of the educational experience.

Shakespeare and the Digital World doesn’t set out to solve the problem of introducing Shakespeare to ten-year olds, but the analytical thinking, asking as Erin Sullivan does questions about the kinds of knowledge they want to help students acquire, how to develop this knowledge, and how to show it has been done, can be applied at any level.

Finally on the subject of education, the University of Warwick’s Massive Open Online Course Shakespeare and his World is to be re-run from 29 September 2014. I took it first time round and found it enjoyable, engaging and informative and I’d recommend it for any life-long learners wanting a different approach to the subject.

Your ideas for teaching Shalespeare are great. The general population in the US perceives it as too hard. Being open to the poetry/language, seeing/hearing the play on the stage or film makes it come alive , you hear the jokes and understand the intrigues. I think Shakespeare is the ultimate team teaching vehicle…art, history, language all take part. My experience in high school was a trip to a Shakespeare festival each fall to see the play we would study that semester. Memorable.