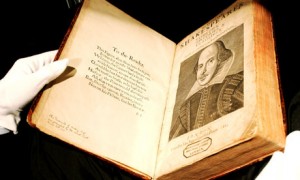

Shakespeare’s First Folio is back in the news again, with a documentary presented by actor Simon Russell Beale having been broadcast on 9 September. It’s part of the series The Secret Life of Books, a fascinating look at the process of creative writing. The whole series is available to watch again until 7 October. Other authors and their books put under the spotlight include Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway. Even if you’re not able to get the episodes on BBC’s IPlayer there are a number of clips available on the BBC page, including one in which Beale examines a copy of the Folio with the guidance of Professor Sonia Massai, and another in which he performs different versions of the “To be or not to be” speech from Hamlet.

As they point out, it’s the lack of original manuscripts that has made the 1623 First Folio so important to all those wanting to study Shakespeare, though it’s by no means surprising that his drafts and working copies have disappeared: hardly any theatrical manuscripts from the time have survived. Frustration at this situation drove scholars in the past to extreme lengths, including forgery. Simon Russell Beale examines three plays which he knows particularly well: Hamlet, King Lear and Timon of Athens, to work out what if anything can be deduced from studying the Folio texts. Timon is the only one of the three that exists only in the Folio, and indeed no record exists of the play even being performed in Shakespeare’s lifetime. Can we find within the Folio texts the beginning or middle of the writing process, or is the Folio simply the final product?

As part of his investigation he looks at the process of printing itself, and the difference between the quarto editions of individual plays as against the folio, talking with directors Nicholas Hytner and Sam Mendes about what happens to any text as the play is being rehearsed and performed.

Beale and Nicholas Hytner consider the idea that Timon of Athens is a draft rather than a finished text: it’s a play which is so unsatisfactory that it is still rarely performed. Was it written by a Shakespeare on the verge of a nervous breakdown? They consider the possibility that the inconsistencies were caused by the fact that the play was a collaboration between Shakespeare and Thomas Middleton, a playwright who specialised in bitter satire. Middleton is thought to have written much of the first part of the play, but as Beale notes, it’s the second part of the play, Shakespeare’s section, that poses the greatest number of problems, among with some great pieces of writing. Was Shakespeare supposed to come back and revise it? And why, then, didn’t he? Beale speculates that perhaps Shakespeare was, if not on the verge of a nervous breakdown, depressed himself.

Maybe Shakespeare moved on to another project, another play that shares some of the same dark features but which is far more successful, King Lear. Here Beale considers Shakespeares’s source material The True Chronicle History of King Lear and its relation to the finished play. Shakespeare changed the source play in many ways, most strikingly the end where Cordelia does not die, and Beale suggests that there must have been reasons why Shakespeare made such a radical and brutal change. Perhaps it’s due to the editing of the video, but it’s not made clear that there are a number of possible sources for King Lear, several of which do include the death of Cordelia, so Shakespeare may have been choosing from a number of alternatives rather than simply inventing something new. Beale and Massai conclude by agreeing that no matter how much individual ideas may vary, what makes Shakespeare so endlessly interesting is that his work is open to innumerable interpretations. Accompanying the series is a free app to download: just go to the BBC series page and follow the links.

To find out more about the Folio, here’s a link to pages from the British Library and the Folger Shakespeare Library. And if you want to look at Folios and Quartos online, the British Library’s Shakespeare in Quartos project digitised all the quartos they hold (click on The Texts to find individual copies). Several complete Folios have been digitised: one from the Bodleian Library in Oxford, and two on the Internet Shakespeare editions: one from Brandeis University and another from the University of New South Wales, and there’s a searchable First Folio from the University of Chicago. The Secret Life of Books is only available to download until 7 October so if you want to watch it you’ll need to act quickly.

Sylvia, What a great blog. I came across it looking for material on women directors at the RSC. I used your post ‘here come the girls’ for a piece I have written for a research blog called The Conversation: http://theconversation.com/uk – duly acknowledged and linked to, of course. It is wonderful to see the archives at the SCLA being used so creatively.

Thank you Kate! Always pleased to hear the blog is being useful.