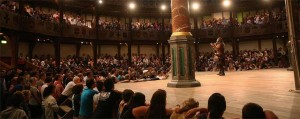

A couple of weeks ago Gregory Doran, the new Artistic Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, was “In conversation” with Michael Dobson, the head of the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon. The session was recorded on video and is now generously available on YouTube. In addition to talking about his early influences he inevitably spoke about his plans for the RSC under his Directorship. One subject that came up was the idea of “Company” or “Ensemble”, and Doran suggested that these words can mean very different things to different people.

A couple of weeks ago Gregory Doran, the new Artistic Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, was “In conversation” with Michael Dobson, the head of the Shakespeare Institute in Stratford-upon-Avon. The session was recorded on video and is now generously available on YouTube. In addition to talking about his early influences he inevitably spoke about his plans for the RSC under his Directorship. One subject that came up was the idea of “Company” or “Ensemble”, and Doran suggested that these words can mean very different things to different people.

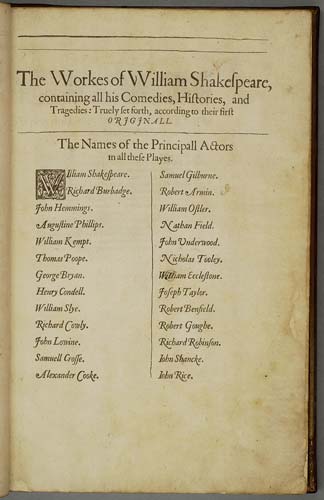

The first professional acting troupes formed companies under the protection of a nobleman whose name they took, such as Lord Strange’s Men. The “Names of the Principall Actors in all these Playes” are given their own page in Shakespeare’s First Folio, acknowledging the importance of actors to the plays. Their names have a particular magic: these men and boys were the first to create Shakespeare’s characters, and in some cases, like Richard Burbage’s, the roles were written for them. Shakespeare’s acting company wasn’t static, and both William Kempe and Robert Armin are named on the list. We know Kempe played the comic lead Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing, but when he left The Chamberlain’s Men he was superseded by Armin, a more subtle and musical actor for whom Feste in Twelfth Night and the Fool in King Lear were written. It’s interesting to think that if this change of personnel hadn’t happened, Shakespeare’s plays might have been quite different.

The closest-knit companies have usually been those that tour together, like the Crummles Company which Charles Dickens created in his novel The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, though Dickens uncovers the petty squabbles and jealousies created by the familiarity of the group. In Shakespeare’s play Hamlet the touring actors are a small, closely-knit group “the tragedians of the city”, that Hamlet has seen performing together many times.

By the late nineteenth century, most companies operated under the control of an actor-manager who took both most of the artistic decisions and the best parts. The most powerful was Henry Irving who led the Lyceum Theatre in London from 1878 to 1901, performing most of the leading roles. The reason for this was not simply vanity, but economic. Then as now, audiences came to see star performers, making it difficult for younger actors to progress.

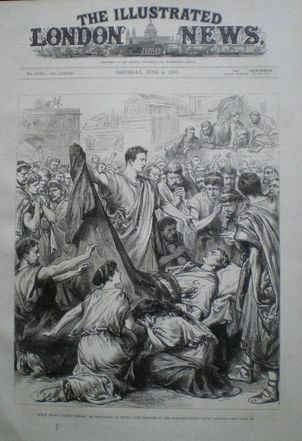

But in 1881 another way of performing was demonstrated to London theatregoers. The German Saxe-Meiningen Players visited Drury Lane Theatreand their performance of Julius Caesar created a sensation. The Duke of Saxe-Meiningen’s theory was that all the actors should be drilled by a director, including the hundreds of supernumeraries (extras) who made up the Roman mob. Both Charles Edward Flower, the founder of the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford, and the young actor Frank Benson, went to see them perform. Flower wrote up his impressions in a hand-written essay on acting;

“It … carried everyone by storm in Julius Caesar. The acting throughout was of the first order, not only Brutus, Cassius and Antony, were acted by men of great power but all the other parts down to the smallest were well and intelligently played.”

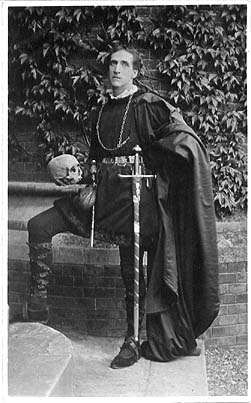

It would be several years before Benson and Flower were to meet, but seeing the Saxe-Meiningen company increased Flower’s ambitions for the newly-opened Memorial Theatre and when Benson was engaged to run the Festivals he must have hoped that something similar would develop.

For several years Benson indicated that he worked on Meiningen principles, but although he operated a semi-permanent ensemble there was never any question of who would play the lead. Actors in his company would sing:

The Meiningen system is nothing but rot;

Good-bye, poor actor, good-bye,

For Benson’s parts are the best of the lot;

Good-bye, fond actor, good-bye.

Gregory Doran explained that his view of ensemble is somewhat different from Michael Boyd’s. Boyd has done much to bring the whole organisation together. But Doran’s opinion is that Shakespeare wrote hierarchically, with actors taking particular types of parts, and it’s unlikely that the leading actors would have taken minor roles. Doran’s idea of ensemble doesn’t exclude bringing in leading actors for short seasons as he will with David Tennant playing Richard II next winter.

What then of the idea of a semi-permanent ensemble? Doran seems to believe if you provide the right environment it may happen. He said “you can’t cast an ensemble, you can only grow an ensemble”. If you want to spot this section on the recording it’s about 44 minutes in. Doran leads workshops with each company as they comes in, to help improve skills. And Doran’s working methods are designed to allow all the actors working on a play to feel a sense of ownership: for the first week of rehearsals the cast read the play around the table, getting a sense of the whole work rather than just their own parts. Interesting times ahead!