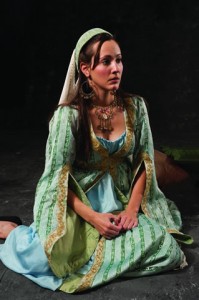

The Merry Wives of Windsor is set in the depth of winter, the season Shakespeare associates with eating, drinking, telling stories, singing, and practical jokes. It’s also one of the few plays for which Shakespeare invented the plot, and he drew on popular myth for the climax of the play. Mistress Page explains:

There is an old tale goes that Herne the hunter,

Sometime a keeper here in Windsor forest,

Doth all the winter-time, at still midnight,

Walk round about an oak, with great ragg’d horns;

And there he blasts the tree and takes the cattle

And makes milch-kine yield blood and shakes a chain

In a most hideous and dreadful manner:

You have heard of such a spirit, and well you know

The superstitious idle-headed eld

Received and did deliver to our age

This tale of Herne the hunter for a truth.

Herne was thought to have lived in the time of Richard II, and the ancient tree became known as Herne’s Oak, a place where “many …do fear /In deep of night to walk”. Playing a trick on Falstaff, the wives suggest that he disguise himself by wearing a stag’s horns strapped to his head and meet there at dead of night for their long-delayed assignation. For more on the Smirke painting, follow this link.

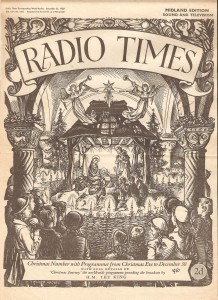

In the final scene of the play the residents of Windsor arrange for Falstaff’s humiliation to be complete: local children dress up as fairies and dance around the oak pinching Falstaff as they go. Mistress Page:

Let them from forth a sawpit rush at once

With some diffused song; upon their sight

We two in great amazedness will fly:

Then let them all encircle him about

And, fairy-like, to-pinch the unclean knight,

And ask him why, that hour of fairy revel,

In their so sacred paths he dares to tread

In shape profane.

Mistress Ford continues:

And till he tell the truth,

Let the supposed fairies pinch him sound

And burn him with their tapers.

The locals don’t get it all their own way, as Anne Page uses the opportunity to elope with the man of her choice instead of either of the suitors chosen by her parents, but the play ends with the victory of the Wives and their husbands over Falstaff, the interloper.

Not least because of the popularity of Shakespeare’s play, Herne’s Oak, in Fairies’ Dell, Windsor, attracted visitors in the eighteenth century. There must have been some confusion about the identity of this tree, because when gales blew it down in 1863 it was claimed by some that this was in fact a tree planted later to replace the original tree which had been felled in the 1790s.

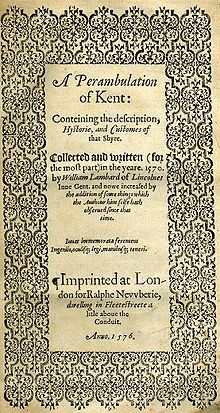

William Perry, Wood Carver to the Queen, investigated and in 1867 published a book, titled A Treatise on the Identity of Herne’s Oak Inferring the Maiden Tree to Have Been the Real One. He had compared the account appearing in Samuel Ireland’s 1791 Picturesque Views of the Thames, and documents on the Park, as well as making site visits before concluding that the blown-down tree was the original one. Perry wasn’t unbiased though. He had been given pieces of the tree from which to make souvenirs, so its authenticity was important, and the argument is reminiscent of the discussion about objects made from Shakespeare’s Mulberry Tree in New Place Gardens, Stratford, which had been cut down about a century before.

It’s now popularly thought that the original tree was felled as a result of George III wanting to replace some of the old, unsightly trees with young ones. The trees seem to be fated, because following the 1863 storm another was planted which in its own turn blew down in 1906. Like most legends, it’s hard to know how much of it is true: the Falstaff story though comes straight from Shakespeare’s imagination.