22 November is Saint Cecilia’s day, when we should be celebrating music in all its forms, yet on Tuesday morning BBC Radio 4’s Today programme broadcast a piece criticising the fact that only a small minority of people attend ballet, opera and classical music events despite sixty years of Arts Council England funding for the arts. It suggested that ACE has failed to bring “great art to everyone”.

22 November is Saint Cecilia’s day, when we should be celebrating music in all its forms, yet on Tuesday morning BBC Radio 4’s Today programme broadcast a piece criticising the fact that only a small minority of people attend ballet, opera and classical music events despite sixty years of Arts Council England funding for the arts. It suggested that ACE has failed to bring “great art to everyone”.

Almost immediately a deluge of tweets was launched, and before the end of the day Guardian online had produced two pieces refuting these claims, here and here. The Today piece went for the easy targets while failing to mention the rest of the work supported by ACE. Theatre companies, galleries, museums and libraries all strive to make the arts in all forms to new audiences. In the past year or so the Arts Council has had to make massive cuts and 200 organisations have completely lost funding, but the BBC’s piece was less about the effect of these cuts than an attack on the support to elitist art without an acknowledgement of the work done to broaden access to the arts in hard times.

Those involved in music and dance already felt themselves under attack, as the Education Secretary, Michael Gove, recently announced that arts subjects will be excluded from the new English baccalaureate. It’s feared these subjects will find themselves excluded from schools when not part of the required curriculum. Unless students are introduced to the arts at school they may never become audiences later in life. The campaign is being led by major figures in the arts, and if you’d like to support it, follow this link.

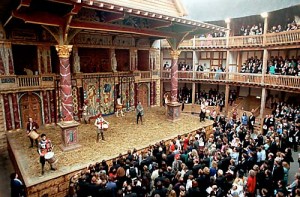

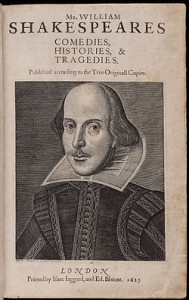

I don’t wish to enter the ongoing debate about subsidy and the arts, but Shakespeare is supported by Arts Council England, the Royal Shakespeare Company receiving substantial funding from ACE for both the transformation of its theatres and ongoing artistic work. The National Theatre is the regular stager of Shakespeare that is also a major recipient of ACE funding. Shakespeare’s Globe shows what can be done without regular funding since the building was completed in the 1990s. All three organisations have active education departments that aim to connect young people with Shakespeare, theatre or both.

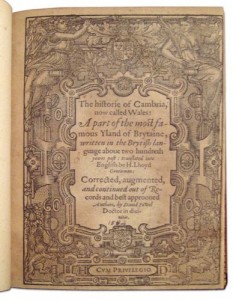

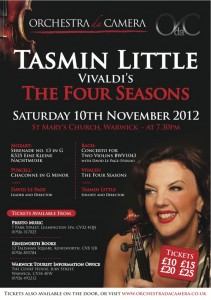

The value of the arts, in particular music, has been championed for centuries. A book entitled The Praise of Musicke, published in 1586, claims that music “encourages chastity, moveth pittie, allayeth anger, restoreth madmen to their wits, cures diseases, and driveth away evil spirits”.

Shakespeare’s love of music is obvious from the number of occasions when he uses it to set a mood or to reflect the action of the play. Even when Richard II is in prison, in the scene before his death, he hears music:

Keep time: how sour sweet music is,

When time is broke and no proportion kept!

So is it in the music of men’s lives.

And here have I the daintiness of ear

To cheque time broke in a disorder’d string;…

This music mads me; let it sound no more;

For though it have holp madmen to their wits,

In me it seems it will make wise men mad.

Yet blessing on his heart that gives it me!

For ’tis a sign of love; and love to Richard

Is a strange brooch in this all-hating world.

A couple of projects have recently been announced linking Shakespeare’s work with popular music. In Glasgow Hip-Hop Shakespeare is exploring cultural parallels between Shakespeare and hip-hop artists, using Hamlet, Othello and Romeo and Juliet to look at issues of responsibility and relationships. It’s a good example of how the arts can provide experiences that enrich people’s lives.

And a new musical is in preparation that is based on the story of Romeo and Juliet, using the music of songwriter Jeff Buckley.

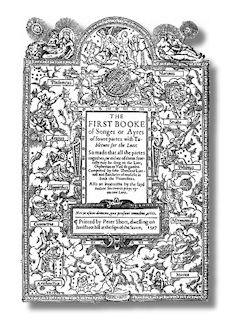

Finally, I’ve just spotted this clip on YouTube of Sting performing a song by Dowland to the “lascivious pleasing of a lute”. It won’t be to everyone’s taste, but I found it refreshing to hear music of the period sung in a modern style, and shows that music of Shakespeare’s period still has a place.