Hung be the heavens with black, yield day to night!

Comets, importing change of times and states,

Brandish your crystal tresses in the sky,

And with them scourge the bad revolting stars

That have consented unto Henry’s death!

King Henry the Fifth, too famous to live long!

England ne’er lost a king of so much worth.

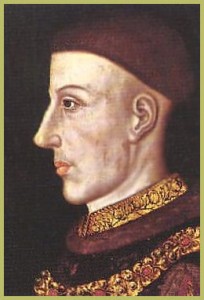

At the beginning of Henry VI Part 1, the Duke of Bedford, the brother of Henry V, speaks these lines at Henry’s funeral. This service took place in Westminster Abbey 590 years ago today on 7 November 1422. Henry had died in France in August and his body was brought back to England with great ceremony. Four horses drew the chariot bearing his coffin into the Abbey right up to the choir screen and it took nine years for his magnificent tomb with its chantry chapel to be completed.

On the inscription on his tomb Henry was referred to as the “hammer of the Gauls”. He was a great national hero who would have been remembered even without Shakespeare’s play. Part of his funeral “achievements”, a saddle, helm, sword and shield, were for centuries on display above the chantry and were only removed to the Abbey’s Museum in 1972. It’s tempting to think that Shakespeare must have seen them, with the tomb having been viewed by visitors to the Abbey for over 150 years. The British Museum’s exhibition Shakespeare: staging the world puts them back on display among other items that would have been familiar to Shakespeare’s contemporaries.

The arms on display here may have been purely ceremonial, but they are still powerful objects. Faded and damaged, they are among the most touching in the exhibition. It’s almost impossible to imagine how they appeared at the time of Henry’s burial, and astonishing that such fragile items, kept in such a public place, have survived.

Arms were traditionally displayed after successful battles. The Chorus in Act 5 of Henry V says that the people hoped to see the carrying of “His bruised helmet and his bended sword /Before him through the city” on Henry’s return after his victory at the battle of Agincourt. In Shakespeare’s play Richard III Richard Duke of York refers to arms being put on show as symbols of victory.

Now are our brows bound with victorious wreaths;

Our bruised arms hung up for monuments.

With hindsight we and Shakespeare see Henry’s death as the beginning of the end. Within only a few lines of Bedford’s speech noting that comets are predictions of doom a messenger arrives with news that many of England’s territories in France have been lost, not because of supernatural intervention or French deceit, but because of a lack of resolve by those in power:

No treachery; but want of men and money.

Amongst the soldiers this is muttered,

That here you maintain several factions,

And whilst a field should be dispatch’d and fought,

You are disputing of your generals.

These disputes provide the basis for the Wars of the Roses which only ended with Richard III’s death.

The contrast between the grief that met Henry V’s death and his elaborate funeral and what happened to Richard III after his defeat at the Battle of Bosworth could not be more stark. The location of the church in which Richard had been buried, Greyfriars in Leicester, disappeared, but the much-publicised recent excavation of a car park has confirmed where it was and it’s possible that his grave has been found.

DNA tests on the bones will not yield results for another couple of months, but there is already much debate about where they should be re-interred should they prove to be Richard’s. There are calls for a state funeral in Westminster Abbey, for his return to his centre of power in York, while the official line favours a reburial in Leicester. There has even been a jokey suggestion that he should be buried in Worksop because it’s midway between Leicester and York. This excitement is only partly because of the desire to give a resting place to a maligned king. Richard’s grave would also be a tourist attraction and provide a significant boost to the local economy.

It’s ironic that although Shakespeare has been blamed for Richard’s reputation (though he only followed the official version of history), it is Shakespeare’s fictional portrait of a compelling but psychopathic monarch that has created the interest in the real man’s final resting place.

I’m rooting for York…!:). We already have the Richard III Museum, which could be usefully expanded with the revenue that this would bring and after all, he was Richard of York.

I’m with you! If identification is conclusive it would be good for him to return to the place with which he was most closely associated.

I think it should be York . He was after all the last of the house of York. In 1483 Richard planned a chantry foundation of 100 priests in the Minster so probably intended to be buried there himself (can’t find the exact source for this but it’s mentioned in DNB and the VCH). However I suppose he may have changed his mind with later events – his wife Anne Neville who died in March 1485 is buried in Westminster Abbey and his 10 year old son Edward who had died in 1484 is buried at Sheriff Hutton (part of the Neville estates).

As he was an anointed king, I do hope some dignity is accorded to the decision if they do reach certain or probable identification.