Although all sport is competitive, many of those which feature in the modern Olympics began as a way of training for warfare. Shakespeare brings several of them into his plays, including wrestling, archery and fencing.

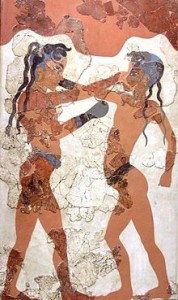

Self-defence sports wrestling and boxing date back to the days of the Greek Olympics. Bare-knuckle boxing was a somewhat more refined version of hand to hand fighting made respectable in the 1840s with the Queensberry rules. Wrestling has always been more popular, less controlled, with a high risk of injury. In As You Like It, the hero Orlando fights with and defeats the Duke’s wrestler, a man who has a fearsome reputation for breaking the ribs of his opponents and coming close to killing them. The clown Touchstone comments on the roughness of the competition: “It is the first time that ever I heard breaking of ribs was sport for ladies”.

Many sports were seen as more suitable for the gentry. In his 1570 book The Scholemaster, Roger Ascham suggests a whole list of recreations: “to ride comely, to run fair at the tilt or ring, to play at all weapons, to shoot fair in bow or surely in gun …and all pastimes generally which be joined with labour, used in open place and on the daylight, containing… some fit exercise for war”.

Gervase Markham, writing in Countrey Contentments, said that the “most manly and warlike” of recreations is “the hunting of wild beasts”. In As You Like It the banished Duke, living in the forest, recognises that he and his followers are the invaders:

And yet it irks me, the poor dappled fools,

Being native burghers of this desert city,

Should in their own confines with forked heads

Have their round haunches gor’d.

Olympic equestrian events began as methods of training horses for battle, and several relate to hunting, in itself originating as ways of acquiring skills for war. Even some of the events on the track, like throwing the javelin, started life this way.

Archery features in several plays, from the relatively genteel leisure pursuit practised by the Princess of France in Love’s Labour’s Lost to the use of longbows at the Battle of Agincourt in Henry V where the archers won the battle for the English. It was rendered obsolete by the increasing use of firearms. William Harrison, in his 1587 Description of England states that archery was by then merely a pastime rather than a training for battle: “our strong shooting is decayed and laid in bed”.

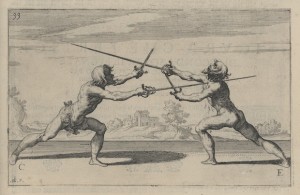

It’s swordplay, though, that is most in evidence in Shakespeare’s works. In Romeo and Juliet, the young men of Verona know well the language and techniques of fashionable swordfighting. Mercutio accuses Tybalt of being “a duellist, a gentleman of the very first house, of the first and second cause. Ah, the immortal passado, the punto reverso, the hay!”

While fighting with personal weapons was common, rehearsing battles by jousting had fallen out of favour. John Stow in his Survey of London, comments that “The marching forth of citizens’ sons, and other young men on horseback, with disarmed lances and shields, there to practise feats of war, man against man, hath long been left off”.

Foils were originally developed as practice swords to train men for combat, and it was fencing, the refined version of swordfighting, that survived and remains an Olympic sport.

The best example is in Hamlet, where the Prince and Laertes fence against each other. Instead of a mere competition, Laertes and Claudius plan to turn it into murder. One of the foils will have an “unbated” point, which will also be poisoned.

I’ll touch my point

With this contagion, that, if I gall him slightly,

It may be death.

Fencing was a sport for the gentry, but in order to be convincing, stage actors would have had to have learned some skills. There were several fencing masters in London who could have taught them like the Italian Vincentio Saviolo. There’s a fascinating page on the history of fencing here.

Fencing was a sport for the gentry, but in order to be convincing, stage actors would have had to have learned some skills. There were several fencing masters in London who could have taught them like the Italian Vincentio Saviolo. There’s a fascinating page on the history of fencing here.

If you’d like find out more, the Wallace Collection in London is currently holding an exhibition entitled The Noble Art of the Sword: Fashion and Fencing in Renaissance Europe, until mid-September. The curator of the exhibition, Tobias Capwell, was interviewed on Radio 4’s Midweek on 1 August, and a summary and link to listen again is here.

As you say, Sylvia, Shakespeare had, at best, an ambivalent attitude towards sport and most sporting occasions in his plays turn out badly for someone. John Dugdale made a similar point in The Guardian last week: http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/booksblog/2012/jul/27/london-2012-shakespeare-olympic-champion