This week I have been attending the British Shakespeare Association’s conference at the University of Stirling. What follows is the text of my paper:

This week I have been attending the British Shakespeare Association’s conference at the University of Stirling. What follows is the text of my paper:

The idea for my project Listening to the Audience began when, at an international Shakespeare conference in 2012, I noticed how many of the people presenting papers referred to their personal memories of theatre productions (mostly by the RSC) as inspiration for their ideas. After the conference most of those memories would be lost, leaving only the “official” records, the reviews produced by professional writers, for people to consult in the future.

In his foreword to the book Shakespeare, Memory and Performance, Stanley Wells explains how performances we never saw, like those of Sarah Siddons, “reverberate in our imaginations” because of what people have written. But “these performances have passed through the transfiguring power of the imaginations…of those who witnessed them”. The writer, or the academic, is using his experience to create a subjective, selective work of art just as a painter does.

Wells is talking largely about critics from past centuries, but his point applies to modern writers who are just as subjective, and just as likely to be “interested in coining a flashy phrase rather than recording objective truth”. In fact this subjectivity can be an advantage. He writes: ” We should gain no impression of the impact of the performances…if they did not…tell us…something of the emotional and intellectual impact that they had upon their creators and which is the fundamental source of the value we place upon theatre”.

These published opinions have authority because theirs are the only voices heard. But I wanted to record the opinions of people who were not professional reviewers, but were just members of the audience. I had worked for decades with the RSC’s archives and met hundreds of people who had vivid memories. Were they not valid too?

Initially I thought I would be making it possible to fill in gaps in the record: some productions did not receive many reviews, and video only became routine in the 1980s. I expected to ask about specific moments in early productions. I very quickly found that I wanted to record some practitioners: many retired theatre professionals live locally and they are all getting older. And I looked around for other projects with similar aims.

The main one was the British Library’s Theatre Archive project, which records people talking about the period 1945-1968 when censorship was removed.

I already knew about the Stratford Society’s Oral History recordings that had interviewed a range of people about their lives and work in Stratford.

I discovered Helen Freshwater’s 2009 book Theatre and Audience, which looks at theatre’s ability to influence, illustrated by examples of performances with active audience involvement.

During 2012 the BBC Listening Project began to be broadcast on Radio 4, conversations of ordinary people talking about something important to them.

Locally in Stratford this has spawned the new Stratford Listening Project, a community project aimed at bringing people together to discuss the past, encouraging creativity through artwork, soundscapes and song.

This project linked up with the existing Warwickshire Reminiscence Action Project that stresses the social and health benefits of reminiscence, removing social isolation, bringing history alive, and improving self-esteem and confidence. It’s a project that works with the NHS, often including people with dementia.

The RSC itself has recorded VoxPop interviews immediately after performances under the title What the Audience Thinks.

And just recently I’ve found out about an organisation of theatre professionals and academics, the British Theatre Consortium who have just completed an AHRC project under its Cultural Value programme. “Theatre Spectatorship and Value Attribution”, looking at audience engagement, and interviewing audiences up to a year after the performance, which will be reporting soon.

The projects I’ve listed approach memories in very different ways, from being therapy for the very old to providing material for school history lessons. Some are seen as being of value for the listener as much as the interviewee, some are purely archival.

In the introduction to his edited book Shakespeare, Memory and Performance, Peter Holland notes that memory has become a fashionable academic topic, moving across boundaries from the humanities and social sciences to the scientific study of the brain and medicine where health can be improved through a combination of physical, mental and social wellbeing.

The neuroscientist James McGough, in his recent book Memory and Emotion, “explores how memories are made and preserved; why some experiences fade and disappear with time; how stress hormones affect the consolidation of memory…and what studies of extraordinary memories and disorders tell us about the workings of the brain”.

Erin Sullivan has recently noted that “No fewer than four major international centres of the study of the history of emotions have emerged in about as many years” in London, Germany and Australia. She calls this an “emotional onslaught”.

The Queen Mary Centre for the History of the Emotions defines its purpose “to provide a focus for interactions between social and cultural historians of the emotions on the one hand, and historians of science and medicine on the other. It also seeks to contribute both to policy debates and to popular understandings of all aspects of the history of emotions”.

The Australian Centre states “Emotions power performance”, and examines how “emotions were performed and expressed through art, music and theatre…and connects them with a modern audience”.

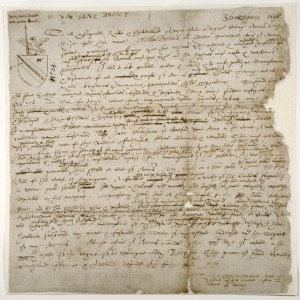

I’ve become very interested in the link between performance, emotion and memory. Certainly the idea that we remember best events that are the most emotional is not new. Francis Bacon, in The New Organon, published in 1620, wrote “memory is assisted by anything that makes an impression on a powerful passion, inspiring fear, for example, or wonder, shame or joy.”

Audiences respond emotionally to theatre, and Shakespeare’s plays provoke the full range of emotions listed by Bacon. Hamlet hopes the play performed before Claudius will provoke him to proclaim his malefaction, and Thomas Heywood, in An Apology for Actors, 1612, tells as fact the stories of people who did just that.

In my recordings, I can’t say I’ve found anyone who responded to performance quite that strongly, but here are three clips of memories of Shakespeare in performance at the theatre in Stratford.

This woman was 17 or 18 when she saw David Warner’s Hamlet in 1965.

What I like about her recording is that she remembered almost nothing except David Warner, and couldn’t even describe his performance in any detail. What she did remember was her response – knitting herself a red scarf and wearing it to the show. And she admits that the performance might not have been very good – but that wasn’t important.

This woman recalls Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V in 1984, and Michael Sheen’s some 10 years later. She was 34 at the time.

Notice that she admits her memories might be inaccurate, might be hindsight. And when she talks about Kenneth Branagh and Michael Sheen, she paraphrases their thoughts as Henry, interpreting their actions in her own mind.

This man recalls Peggy Ashcroft playing Cleopatra in 1953, 61 years ago, yet as you will hear, it’s fresh in his mind. He was 18.

He can still “see” Peggy Ashcroft erotically rolling on a tiger skin rug – what an impression it made on his 18-year old mind. But he knows he’s probably exaggerating. He also can clearly “hear” her voice, mimicking “Can Fulvia die?”.

“Emotion powers performance”. I started wanting to supplement the official record, to lessen the authority of the reviewer in favour of the democratic views of the audience. I am still interested in specific detail, but after reading about memory, and interviewing people, I’ve found that it’s the emotion they remember – that may or may not link to a particular event. Details may be misremembered, but that’s not important. For an emotionally powerful performance you need to generate intensity, to allow the audience to focus, great plays, and great performances.

These three recordings are about great performances, though to be fair two of the three did also recall other people in the production. But I’ve yet to hear much about the sets, though costumes are often remembered. The other thing that is stressed is the speaking of the verse.

Stanley Wells suggested that we place value on theatre because of its emotional and intellectual impact. What is different about theatre that makes this more likely than watching films or TV? Is it powerful because it’s live, because it’s shared?

And modern research into health indicates that the value of emotional experiences may have much more long-term impact and value. Theatre offers audiences a safe way of experiencing emotion, so for theatre to have real value, maybe it needs to provide big memorable experiences. You can hear in the voices of those interviewees how they enjoy the process of revisiting their memories. Does the act of remembering a performance, years later, benefit our physical and emotional well-being, and if so, does this mean that theatre really is good for us?