The Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, has just opened a new exhibition on the subject of heraldry, entitled Symbols of Honour: Heraldry and Family History in Shakespeare’s England.

We think of coats of arms as belonging only to the most noble and royal families, and to organisations, but in Shakespeare’s time, according to Nigel Ramsay, co-curator of the exhibition, it was a “flourishing, live world”, and coats of arms could be awarded to “up and coming merchants and gentry, people lower down the social scale”, just like Shakespeare.

The Folger Shakespeare Library has in its collection much that does not directly link to Shakespeare, including more than a hundred heraldic manuscripts. These have not often been examined, but among them is ” the oldest copy in the world of the first English book of genealogies, Pedigrees of some Noble Families, from no later than 1525″.

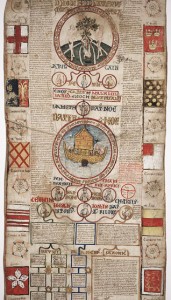

As well as drawing on its own holdings, the Library has borrowed items from other sources. The pedigree scroll of Edward IV, from the Free Library of Philadelphia,is, according to Ramsay, “one of the most splendid pedigree rolls there is.” It dates back to the 1460s, and has “a late medieval form of beauty: crude, vigorous, and bright,” he says. “And it belonged to a king. It’s very rare to be able to say that.”

From London, the College of Arms has lent its three drafts of the Shakespeare Coat of Arms. Two of these were on display in the Searching for Shakespeare exhibition held at the National Portrait Gallery in 2006. Both were produced by the Garter King-of-Arms, Sir William Dethick in 1595, and its thought the fee paid almost certainly by William, though in the name of his father John, was between £10 and £20, a substantial amount of money. The grant was confirmed in 1596. The third document dates from three years later when a further application was made to quarter the Arden arms with the Shakespeare arms, though this seems never to have been used.

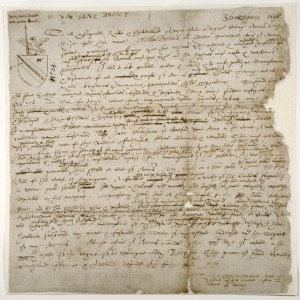

The other document relating directly to Shakespeare (which was also in Searching for Shakespeare) is one that is in the Folger’s collection, dating back to 1602. It is the York Herald (Ralph Brooke)’s complaint against William Dethick. Brooke was critical of Dethick’s laxity in granting coats of arms to people who were not of sufficiently high social standing. This is the famous document in which “Shakespear ye Player” is dismissively written under a sketch of the coat of arms. By this time John Shakespeare was dead and William was the head of the family. Brooke did not single the Shakespeares out: he complained about twenty-three cases including “Dunyan Clarke a plasterer” and “Smith an innkeeper in Huntingdon”. In response Dethick argued that the grant to Shakespeare was justified because John had been a man “of good substance and habilitie”, as well as being a Justice of the Peace and his wife had come from the distinguished Arden family.

There’s a real human side to the items in the exhibition. Heather Wolfe, the other co-curator, has enjoyed examining these “working papers that show the heralds as human beings. I’m excited about any manuscript that gives you a sense of the personalities”. The Heralds appear to have been a strong-minded group, among whom disagreements were not uncommon. For an insight into William Dethick see the blog post by Nigel Ramsay on The Collation, entitled William Dethick and the Shakespeare Grants of Arms.

As well as the exhibition itself there is a magnificent section on the subject on the Folger’s website, including an image gallery and insights from the curators (from which I have lifted some of the quotations in this post). I do recommend taking a look at the site if you’re at all interested in finding out more. The exhibition is on from July 1 to October 26, and is free. It’s supported by events including, on 17 July, a free talk by Kathryn Will entitled Shakespeare’s Coat of Arms and the Early Modern Heraldry Wars.

Pingback: Folger Teaching Shakespeare Institute 2014, Part One | huffenglish.com