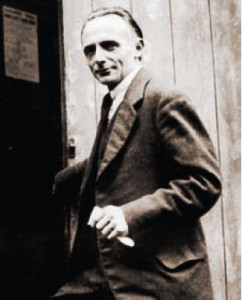

Jeremy Irons is one of our most distinctive and charismatic actors, who has distinguished himself in a whole range of films and TV series. In recent years he’s helped to bring new audiences to Shakespeare with his depiction of Henry IV in the TV mini-series The Hollow Crown, and presented a programme on the Henry IV and Henry V plays in the Shakespeare Uncovered series. In this clip he performs the “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown” speech from Henry IV Part 2.

In a 2013 interview with the Toronto Globe and Mail Irons talked about his work, and the characters he chooses to play, “people who are covering pain, from childhood, relationships, whatever it may be, and getting on with it,” he says. “I’m attracted to characters who are covering. I’m not interested in characters who wear their hearts on their sleeves. I like the tension. I think of my characters as an advent calendar. The life is inside all those closed windows. Scene by scene you open and allow the audience to see in, just a little bit, and then you move on. That’s what I like to do.”

It’s easy to see why he agreed to play Shakespeare’s guilt-ridden, disappointed Henry IV.

Here too is a clip of him talking about the series, and another clip talking to him while on set filming The Hollow Crown.

He’s also been seen on our TV screens in the series The Borgias, and played Antonio in the 2004 film of The Merchant of Venice with Al Pacino as Shylock. He has one of the most distinctive of voices and one of his best-known film roles was as Scar in the animated movie The Lion King, and apparently has provided voiceovers for several Disney World attractions.

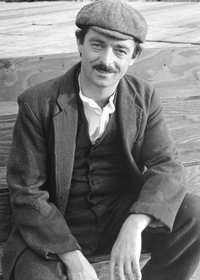

He made his name in 1981 when he starred in the film of The French Lieutenant’s Woman opposite Meryl Streep, as well as appearing as one of the leading characters, Charles Ryder in the TV adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. Within a year he was an established star. There’s a full biography on Wikipedia listing his many film and tv credits, and his numerous awards. He was nominated for a Screen Actors Guild Awards for Best Actor for his role as Henry IV and has won BAFTAs and Golden Globe Awards.

He’s less well known for stage work, but in his early career he mixed TV work with theatre. He’s an accomplished musician, playing a variety of instruments: he did some busking before his career took off. One of his first successes was playing Judas in the musical Godspell that starred David Essex from 1971. I saw him in 1977 at the Piccadilly Theatre in London playing Harry Thunder in the RSC’s revival of John O’Keeffe’s joyous comedy Wild Oats, in a terrific cast that included Lewis Fiander as Rover, Norman Rodway, Zoe Wanamaker, Joe Melia and Lisa Harrow.

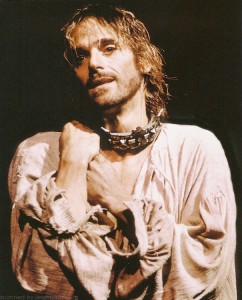

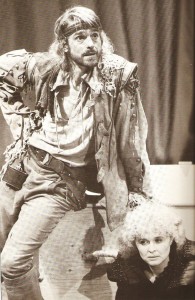

Then in 1986 he came to the RSC to play three roles: Richard II, Leontes in The Winter’s Tale, and Willmore in Aphra Behn’s The Rover.

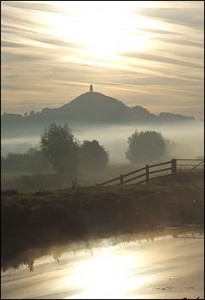

I thought the one that showed him at his best was The Rover, a swashbuckling comedy in which he played opposite his real-life wife Sinead Cusack as well as the young Imogen Stubbs. Eric Shorter wrote “He sails through the amorous havoc and futility….with a beguiling swagger and a sense of ironical humour”, and Irving Wardle likened him to “an accident-prone Errol Flynn”. During the summer he and Sinead Cusack performed at Stratford-upon-Avon Poetry Festival with a programme called Country Houses (obviously relating to Brideshead Revisited). I remember it being a tour de force, with Irons in particular making full use of his glorious voice, an impressive range of different accents and a terrific sense of humour.

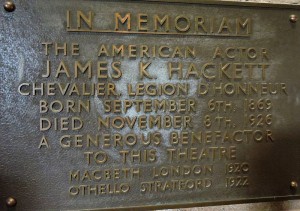

Jeremy Irons is the President of the Stratford Shakespeare Club for the 2014-5 season, the Presidential Evening being on 11 November 2014 when he will be hosted by Roger Pringle who devised and directed the Poetry Festival programme mentioned above. The event is to be ticketed: members are guaranteed places and any tickets not taken will be available to buy on the night. It should be a wonderful evening. Details of membership are on the Club’s website