It’s hardly surprising that Shakespeare’s play The Tempest has been used as the basis for science fiction. A ship and its crew are wrecked on a distant, mysterious island, populated only by a man with magical powers, several strange creatures who act as his servants, and his daughter. The ship’s crew break up into several groups who interact with the island’s inhabitants, upsetting the status quo and threatening to overthrow the magician. This story of how people relate to and govern each other could and has been easily relocated from the strange and exotic island to a host of fictional settings.

The British Library’s new exhibition, Out of this World, is an ambitious look at the history of science fiction, tracing its roots back Shakespeare’s period and even beyond, to books not normally categorized as science fiction like Thomas More’s Utopia.

The Culture Show’s programme traced this history, including a discussion of the first work of science fiction in English, The Man in the Moon, from 1638. Interviews with curators pointed out that like much other art, science fiction is rarely about what it appears to be on the surface. The best science fiction wrestles with the place of the individual in society.

I don’t know if the exhibition includes any references to Shakespeare, but this theme certainly finds expression in The Tempest. On his arrival on the island Prospero has set himself up as the ruler of the island, turning its existing inhabitants into his servants. Caliban complains

I am all the subjects that you have,

Which first was mine own King: and here you sty me

In this hard rock, whiles you do keep from me

The rest o’th’island.

Among the shipwrecked courtiers is Gonzalo, who dreams of another kind of government. “Had I plantation of this isle … and were the King on’t, what would I do?”, he asks. He suggests a commonwealth where all would be equal:

Riches, poverty,

And use of service, none; contract, succession,

Bourn, bound of land, tilth, vineyard, none.…

All things in common Nature should produce

Without sweat or endeavour: treason, felony,

Sword, pike, knife, gun or need of any engine,

Would I not have.

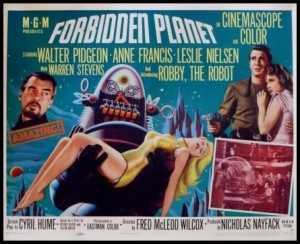

The science fiction film Forbidden Planet was released in 1956, loosely based on The Tempest. The Ariel parallel, Robby the Robot, was the first movie robot to become a hero in his own right. There was no Caliban in the film but an evil force “The Id”, was created by the writer Irving Block because “There are real monsters and demons inside each one of us, without our knowing”, a sentiment which forms the basis of Macbeth.

Shakespeare’s plays are almost all given an unfamiliar setting, in either a far-off country or a safely distant period of English history. This enabled Shakespeare to write safely about current political concerns, but contemporary parallels were not lost on his audiences. In 1601 the Earl of Essex paid for Shakespeare’s company to perform the play Richard II, in which the king is deposed, hoping that the performance would rally support for the Earl’s rebellion against Queen Elizabeth. The play is comfortably set well in the past, but the connection was inescapable. The Queen is said to have responded “I am Richard II, know ye not that?”

The theme of the individual in society is discussed in another of Shakespeare’s most political plays, Hamlet, and sure enough the play is raised in science fiction. The television series Star Trek has made repeated use of Shakespeare’s plays and produced many spin-offs included the wonderfully tongue in cheek translation of Hamlet into “the original Klingon”. Shakespeare and science fiction was also the subject of a post written in 2010 as part of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust’s Blogging Shakespeare.

Interesting blog, Sylvia. I’m familiar with the Freudian Id/Caliban, super-ego/Ariel and ego/Prospero analysis of The Tempest but I’m not sure I agree that the monsters inside us ‘forms the basis of Macbeth.’ It certainly forms the basis of Freud’s view of Macbeth but Freud has dominated Shakespeare for so long, the obligatory Oedipal kiss in Hamlet, repressed sexual desire between Lear and Cordelia, etc. that it’s refreshing to see new productions from young directors who want to explore different approaches to the text.

Andrew, it’s great that people who are much better-read than me comment on my posts! My ideas of Macbeth’s motivation principally come from productions which have, inevitably, been influenced by Freud (which I haven’t actually read). But although Freud might have articulated the idea of the subconscious I don’t believe he invented it, and Kenneth Muir’s intro to the Arden Edition quotes two contemporary sources, James I, who wrote that the devil allures persons “even by these three passions that are within ourselves”, and George Giffard suggested that the power of divels “is in the hearts of men, as to harden the heart, to blind the eyes of the mind, and… to inflame them unto wrath, malice, envie, and cruell murthers”. And at 1.3.133 Macbeth, in an aside, talks of murder before we even meet Lady Macbeth, but the question of who’s responsible for Macbeth’s actions is one that will be argued over for as long as people read and perform the play! Thanks so much for your comments and please keep them coming.

It was brilliant that the R.S.C were able to bring the best of two TV science fiction characters, Patrick Stewart from Star Trek and David Tenant from Dr. Who, together to star in the recent production of Hamlet.

I always feel sorry for poor old Caliban, but he gets his island back eventually. It was typical of most European colonists to assume control of any new land and treat the indigenous inhabitants as servants.

With Gonzalo’s speech Shakespeare returns to a theme of rural simplicity, living off the land as in the Forest of Arden such as in the days of old “Robin Hood”.

While societies become more complicated there is an increased need for this kind of simplicity, hence the popularity of TV programmes such as “Country File” or “Lambing Live”.

As Joni Mitchell sang … “we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden”.

The link between Shakespeare and science fiction seems particularly strong for some reason though I suppose you could say the same for detective fiction… .The idea that there was a golden age always seems to be connected with rural simplicity ignoring the harsh realities of such a life.

I shouldn’t really comment twice but just as a follow-up to Richard above, I agree that, in the post-colonial performance tradition of The Tempest, Caliban gets the island back at the end but it’s not in the text. Although he’s born on the island his mother, Sycorax, was as much of an exile as Prospero and Miranda and in Derek Jarman’s film of The Tempest Caliban is as happy to get off the place as they are! I didn’t see Rupert Goold’s production but, from what I’ve read of it, it sounds closer to Jarman’s view of the island as a lonely, barren place no-one would chose to live rather than the colonised paradise of more conventional contemporary readings.

Thanks for commenting, great to hear from you again. I agree we shouldn’t be too quick to assume that the island is some kind of paradise as you can play it both ways. In Act 2 Scene 1, Sebastian, Antonio and Adrian find the island is uninhabitable, whereas Gonzalo thinks “here is everything advantageous to life”. Why does Shakespeare contradict himself?

About Caliban’s feelings, well he does say “This island’s mine” which I’ve always thought suggests he’d like it back! There’s a wonderful illustration of the final image at the end of Herbert Beerbohm Tree’s production of the play in 1906 showing the ship sailing off into the sunset while Tree, as Caliban, sits on a rock watching it disappear, though whether he was sorry or delighted to see them go I don’t know!