Roland Emmerich, aiming to promote his film Anonymous, has now come up with a video giving 10 reasons why he believes that Shakespeare wasn’t Shakespeare. I’ve been trying to ignore the hype over this film, but I couldn’t resist answering these. If however you’re bored by the whole thing, look away now.

Roland Emmerich, aiming to promote his film Anonymous, has now come up with a video giving 10 reasons why he believes that Shakespeare wasn’t Shakespeare. I’ve been trying to ignore the hype over this film, but I couldn’t resist answering these. If however you’re bored by the whole thing, look away now.

1. Not a single manuscript in Shakespeare’s hand has ever been found. Why are none of his letters home still around?

You might just as well ask why there are no manuscripts of Marlowe’s plays, or why so few personal letters from 400 years ago have survived. The actor Edward Alleyn went on tour and wrote a lovely letter to his young wife that still exists, but any survival is a rarity.

2. Shakespeare’s parents were illiterate, and his daughters couldn’t read or write.

Unfortunately the ability to read doesn’t leave any mark on the historical record, so we don’t know if any of Shakespeare’s family could read. As for writing, John Shakespeare used a mark rather than a signature on documents, but there are records of people who could write putting the sign of the cross on documents. So we just don’t know, but for the record Emmerich is wrong about Susanna as one of her signatures has survived. What does this argument have to do with Shakespeare’s ability to write the plays?

3. Shakespeare writes obsessively about the aristocracy. Ben Jonson’s plays reflect the social class he came from, whereas Shakespeare mocks the lower classes by giving them names like Dull and Mistress Overdone. Would he be a traitor to his class?

Shakespeare wrote plays to be popular. Has Mr Emmerich never noticed the media’s interest in the current Royal Family? This only exists because the public are interested in those who rule them. For the class argument to work Jonson shouldn’t give any of his lower class characters funny names, yes? Pity then about Ferret, Nick Stuff, Trundle and Staggers in The New Inn for one. And Shakespeare often gives humble characters like the soldiers in Henry V’s army dignfied names, like Michael Williams, John Bates and Alexander Court. The names are for comic effect, Mr Emmerich. Marlowe, the son of a cobbler, wrote a play about the monarchy called Edward II, and there were several plays on the subject of Richard III, not just Shakespeare’s.

4. Only a few, poorly-executed signatures by Shakespeare exist.

4. Only a few, poorly-executed signatures by Shakespeare exist.

The few authenticated signatures are all on legal documents. Three on the will written a month before he died, the others on legal documents where space was cramped. Part of the manuscript of the play Sir Thomas More (see left) may well be in Shakespeare’s handwriting, but its authenticity is still in doubt: academics don’t agree. Incidentally Marlowe’s only signature is the sole surviving example of his handwriting, and it’s spelt Marley. So Marlowe couldn’t spell his name either!

5. Shakespeare’s plays and poems don’t reflect his own life, unlike Ben Jonson who wrote a poem on the death of his son and John Lennon who wrote a song about his mother.

This is the “writers write about their own lives” argument. Has Mr Emmerich never heard of imagination? Where does he think Mary Shelley got Frankenstein from, let alone the screenwriters for Godzilla and Independence Day, both films he directed.

6. There’s no record of Shakespeare going to school, but the writer knew subjects like medicine, law, astrology, and he had a huge vocabulary.

There’s no record of any boy attending the Grammar School in Stratford until 1740, although the names of the schoolmasters and their rate of pay are known. Several Stratford boys of Shakespeare’s age acquired a good education: Richard Field became a printer in London, and William Smith, the son of a mercer, went to Oxford. As for all that knowledge, why shouldn’t a young man with an enquiring mind learn an awful lot about these subjects between the ages of 18 and 25? On vocabulary, the English language was expanding all the time, and Shakespeare himself coined several thousand new words.

7. Shakespeare retired in his 40s and never wrote again.

It’s now thought that Shakespeare collaborated on his last play in 1613-14, only 2-3 years before he died. Emmerich says that he can’t compare himself with Shakespeare then cheerfully goes on to do so, saying he couldn’t imagine himself giving up film-making, so how could Shakespeare give up writing? What sort of evidence is this? Perhaps he should revisit this question in twenty years time.

8, Shakespeare set a third of his plays in Italy and refers to Italian cities in great detail.

I wondered when this would come up, and it’s just not true. That third has to include Cymbeline, where the only Italian thing in the two scenes set in Rome are some personal names, several plays set in Ancient Rome based heavily on historical resources, and Two Gentlemen of Verona in which Valentine travels from Verona to Milan by sea (both are inland). English servants seem to abound in these Italian cities and there’s even a horse called Dobbin in Venice. Italy was a fashionable location for plays, not just Shakespeare’s: Women beware Women, The Revenger’s Tragedy and Volpone were all set there, and John Florio could have supplied Shakespeare with details of Venice just as he did for Ben Jonson.

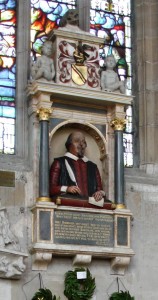

9. Shakespeare’s monument shows a grain dealer.

Another old chestnut. Emmerich shows the illustration of the bust in Holy Trinity Church from Dugdale’s 1656 Antiquities of Warwickshire, in which Shakespeare’s hands are on the cushion before him, and neither paper nor quill are present. It’s been pointed out many times that Dugdale’s engraving is inaccurate, and there’s another early illustration to prove it. Mr Emmerich, why didn’t you show us the rest of the entry in Dugdale? Then we would have seen the English and Latin inscriptions on the monument which refer to Shakespeare as a writer, celebrating “all that he has writ” and calling him “A Virgil in art”. Not how you would describe a tradesman.

10. The will doesn’t mention books or manuscripts, so he didn’t own any.

Shakespeare didn’t necessarily own his own manuscripts, as they would have been the property of the theatre for which they were written. But any books and papers which he did own would probably have been mentioned in the inventory taken to London by Shakespeare’s executor, John Hall, now lost. Historians who have studied wills of the period haven’t found anything suspicious in it, though the mention of the second best bed is eccentric – but presumably even Mr Emmerich wouldn’t try to suggest this had anything to do with the authorship.

I’d be prepared to accept Anonymous as “just a film” if it wasn’t for the fact that Education packs have been prepared to send out to schools, and if videos like the one I’ve linked to weren’t so snide and sneering. Everybody who worked with Shakespeare or knew him, and all their descendants, knew that Shakespeare was genuine. Nobody has ever uncovered any evidence at all that anyone else wrote the plays. Shakespeare’s friends and colleagues wrote that they put the First Folio together to honour him, and his family erected the church bust for him. There’s no reason to doubt the integrity of either. If you want to find out more, the SBT’s Sixty Minutes with Shakespeare is a good place to start, and the Shakespeare Authorship Page is full of tremendously detailed information.

Bravo, Sylvia! :). However, I wouldn’t get so upset about it- remember that Emmerich is simply striving for box office figures in order to recoup the costs of movie-making and exploiting controversy in order to achieve that end. :). I don’t think that history will pay a great deal of attention to him- and in the meantime there is no harm in opening things up for debate in the nations’ schools. 🙂

However, I do dispute your suggestion that Shakespeare made no reference to the death of Hamnet in his writings; the ‘lost twin’ theme that underpins Twelfth Night springs to mind, also Constance’s grief for the death of Arthur in King John:

‘Grief fills the room up of my absent child,

Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me,

Puts on his pretty looks, repeats his words,

Remembers me of all his gracious parts,

Stuffs out his vacant garments with his form;

Then, have I reason to be fond of grief?’

I agree Constance’s speech about the loss of a child could well be a reference to the death of Hamnet – I steered clear, because the whole Oxfordian argument is built on parallels between Oxford’s life and the plays. It is “just a film” but the unpleasant little video which I link to shows Emmerich launching a series of explosions on Shakespeare, ie the intention is to demolish him than encouraging people to take an interest in the plays.

…school children should be presented with both sides of the debate so that they can make up their own minds.

I echo Lucy’s comment totally. This is a clear point by point rebuttal of Emmerich which could be elaborated ten times over and deals with fact, not speculation and wishful thinking. If Emmerich wants Oxford to have written the plays, perhaps he can explain why so many of the rural scenes and characters are clearly grounded in midland England? If, as I suspect he would argue that Oxford knew tenants on his estates and could talk to them, his royal/ courtly argument against Shakespeare promptly collapses for the same reasons

Just recently someone suggested that those who suggest Shakespeare was a nobleman should explain how said nobleman knew about gravedigging. The same could be said about many other jobs: tapster, shepherd, gardener, and most notably, actor and man of the theatre.

That’s entertainment. Why is anyone getting his/her knickers in a twist?

Enjoy the film, and continue enjoying your Shakespeare. They are mutually relatively exclusive.

Sylvia, many thanks for taking the trouble to rebut just some of historical inaccuracies. I was annoyed about it until I saw the film but it is so laughably wrong that now I don’t feel so bad. They can’t even get the right King Richard for the Essex plot!

Just for the record, more than one biographer thought that Mary Arden was literate and we know that Susanna could write. As for Ben Jonson they seem to conveniently forget the huge number of masques he wrote for the court, Jonson was much more of a court writer than Shakespeare who was a King’s player.

Thanks for your comments. I thought the portrayal of Jonson was one of the strangest thing in this strange film, though liked the actor’s performance very much.

Even as an Oxfordian, I would say you’re right with most of your comments, except 3 and 5. I was appealed but sceptical about the Oxfordian theory for a long time. What convinced me was not one of the Oxfordian manifests but Greenblatt’s Will in the World and Jonathan Bate’s Soul of the Age.

I was somehow hoping that they could give me some strong arguments to believe in the Stratfordian’s authorship but what they offered were hundreds of bits and pieces with only peripheral relevance to the work of Shakespeare.

In Anna Karenina you could say even without knowing that Lewin is the character closest to the author even if also other characters are drawn wonderfully.

The same thing you can say about Hamlet. To me there can be no doubt that this character is closer to the author than any other characters not only in this play but maybe in all Shakespeare.

And what do you see: a narcissistic but brillant aristocrat, someone exactly like Oxford.

Thanks for your comment!

I’ve already pointed out that the class argument doesn’t hold water, and although it’s a compliment to Shakespeare that people imagine he must be writing literally from experience, he only ever writes about himself in a very oblique way.

Emmerich says that Shakespeare doesn’t write a poem about his son’s death as Jonson does, but there are two passages which touch on the subject, as I’ve said, obliquely. In King John, Constance’s speech beginning:

Grief fills the room up of my absent child,

Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me,…

And sonnet 33 contains the lines:

Even so my sun one early morn did shine

With all triumphant splendour on my brow;

But out, alack! he was but one hour mine;

The region cloud hath mask’d him from me now.

Shakespeare uses the sun/son wordplay in Henry VI Part 3 “Dazzle mine eyes, or do I see three suns?” and Richard III “Made glorious summer by this son of York”.

You might find this post interesting http://www.abc.net.au/unleashed/3660878.html, and you should look at the Shakespeare Authorship page http://shakespeareauthorship.com/. James Shapiro’s Contested Will is a very good book by an outstanding scholar.

Thanks for your recommendations. I know Shapiro’s book and the authorship website as well as the books by Stephen Greenblatt and Jonathan Bate.

But they all disappointed me exactly for this reason: they come up with hundreds little peripheral snippets, like your quotes on the son references, but fail to present any vital connection between life and work as you can find it with every other great artist.

I think I know Shakespeares works a little and I can tell that the sudden loss of a child doesn’t play a vital role in any play. On the contrary, whenever Shakespeare deals with a loss of a close person, in Hamlet, Winter’s Tale, King Lear and, if you want, Julius Caesar, it’s highly ambiguous, always intermingled with guilt, the reaction rather narcissistic than a compassionate.

If Shakespeare’s work would be a objective and pure artistic view on mankind and the world then I could belive that anybody, also a gentleman of Stratford, could have made it up.

But that’s not the case. There is a “integrity”, as the great Harold Goddard says, in Shakespeare’s work, a coherence of ideas, characters and subjects. Some aspects like narcisissm and jealousy are much more prominent than others. Some character features and constellations appear again and again.

The better I know Shakespeare’s plays the more I realize that they aren’t well-made plays at all, as you would expect from a professional writer, but highly idiosyncratic and self-involved experiments of a extremly narcissistic personality.

So if you want to convince me of the Stratford man’s authorship you have to give me something better than a few son/sun puns.