It’s long been acknowledged that Shakespeare took a great interest in medicine and psychology, and this week the BBC picked up a new article written by Dr Kenneth Heaton indicating that doctors might do well to study Shakespeare to improve their understanding of the link between emotion and illness.

An abstract of the paper is to be found here. Dr Heaton uses examples from several of Shakespeare’s plays which feature symptoms like fatigue and dizziness, and concludes that “Shakespeare was exceptional in his use of sensory disturbances to express emotional upset”.

One symptom that Shakespeare mentions many times is sleeplessness, or sleep disturbance. In sonnet 27 he describes the experience most of us will recognise when our minds continue to race even when we’re tired:

Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed,

The dear repose for limbs with travel tired;

But then begins a journey in my head,

To work my mind, when body’s work’s expired:

For then my thoughts, from far where I abide,

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee,

And keep my drooping eyelids open wide,

Looking on darkness which the blind do see.

Here the experience is pleasant, but in sonnet 28 he writes about being tortured and oppressed by being “debarr’d the benefit of rest”:

But day doth daily draw my sorrows longer,

And night doth nightly make grief’s strength seem stronger.

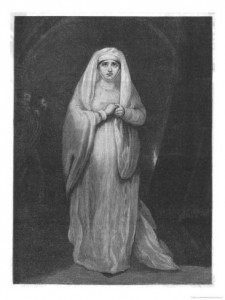

Shakespeare’s use of sleep disturbance to signal emotional trauma reaches its highest point in Macbeth, where Macbeth and his wife are both guilty of the crime of murder. Their symptoms range from “terrible dreams, that shake us nightly”, to sleeplessness: “you lack the season of all natures, sleep”, and Lady Macbeth’s sleepwalking, “a great perturbation in nature, to receive at once the benefit of sleep, and do the effects of watching”. She is also described as “not so sick…as she is troubled with thick-coming fancies, that keep her from her rest”.

As well as seeing apparitions, Macbeth hears warnings:

Methought, I heard a voice cry, “Sleep no more!

Macbeth does murther Sleep,”-the innocent Sleep;

Sleep, that knits up the ravell’d sleeve of care,

The death of each day’s life”…

Still it cried, “Sleep no more!” to all the house:

“Glamis hath murther’d Sleep, and therefore Cawdor

Shall sleep no more, Macbeth shall sleep no more!”

Macbeth isn’t one of the plays that Dr Heaton focuses on, perhaps because it’s so obvious, but an older article published by the same journal looks at the way that in this play Shakespeare uses the metaphor of Scotland as a sick body needing purging or surgery to cure it.

These articles come from Medical Humanities, a journal on the subject of medical ethics and the exploration of the relationship between medicine and the arts. Issues regularly contain poems, acknowledging, as Shakespeare so often does, the links between illness and emotion, and that health isn’t just the absence of disease.

Another article in the most recent issue, Plagued by kindness: contagious sympathy in Shakespearean drama, looks at the metaphor of infection in Shakespeare’s plays, comparing his treatment of the subject with contemporary plague pamphlets and medical tracts.

Shakespeare’s interest in illness, and the number of doctors who appear in the plays, is sometimes attributed to the fact that his son-in-law, John Hall, was a well-known doctor himself. Plague occurred everywhere, including Stratford-upon-Avon, and, in London Shakespeare could have encountered much mental illness, Bedlam already being a hospital for the insane.

It’s interesting that Shakespeare is thought able to teach medical students a thing or two about human psychology and the effects of emotions on our bodies. It’s an unusual reason for studying Shakespeare, but sounds as if it could be worth a try.

What can Doctors learn from Shakespeare? Hopefully, a little humanity!!! Having just emerged from a horrible weekend experience of Leeds A & E after being taken ill on the train and left without pain relief for 8 hours on the basis of their apparent belief that I was a local junkie hustling for drugs (!) rather than someone who was simply travelling through and simply wanted to get home- I can honestly say that Doctors are cold, arrogant, and so certain of their personal perfection that they will happily abuse and neglect the people in their ‘care’.

That said; I personally think that you would be hard pushed to persuade any Doctor to read Shakespeare- they have no interest in humanity, so why they should be at all interested in the HUMANITIES (!) is a mystery to me. 🙂

Sorry to hear about your recent experience, it certainly sounds as if the Doctor who wrote the article is right.

I was delighted to see this blog post; the child of physicians and now a Shakespearean at the University of Georgia, I regularly collaborate with colleagues at our new medical school to develop an integrated humanities curriculum for medical students, and I wrote my recent book, _Shakespeare’s Medical Language_ (Continuum, 2011), with several constituencies – professional Shakespeareans, literary-minded doctors, and “lay” readers of Shakespeare – in mind. I include present-day medical terms as well as historical and literary categories in my index so that physicians interested in Shakespeare’s characters and their bodily and mental health could easily look up ailments or aspects of the senses that interested them. I do in fact have quite a detailed discussion of dizziness or vertigo and the emotional triggers that Shakespeare associates with them (and was inspired to write about vertigo by a lovely, literary neurologist who asked me to “find out whether Shakespeare said anything about migraine auras”).