Christmas Day is always a time for looking back at the year that’s ending and forward with hope.

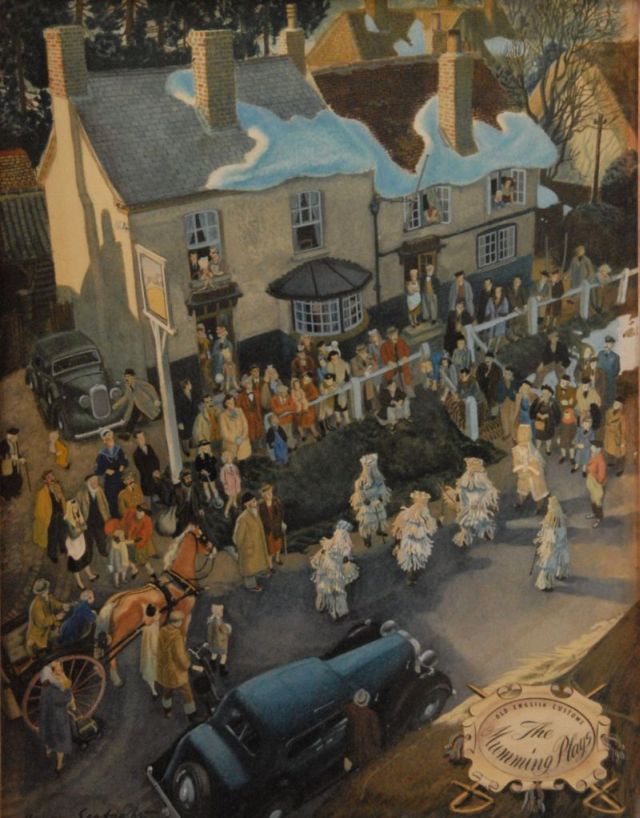

I’ve known this picture of Christmas celebrations in an English village all my life as it used to hang in my parents’ dining room. It was created by artist Henry Seabright as part of an advertising campaign for tyre manufacturer Dunlop, for which my father worked. The title is English Country Customs: the Mumming plays.

At first sight it seems to be a sentimental image of Merry Old England. It shows a group of mummers performing outside a village pub on Christmas day watched by a crowd, including people in party hats inside the pub.

But if you look more closely, it’s not just a rural idyll. Among the villagers are uniformed representatives of the three armed forces. It includes people of all classes from the beggar to the lady of the manor in her fur stole. They are of all ages: a toddler runs at the feet of an old lady with her stick. The picture must date to the late 1940s or early 1950s, and shows a country in a state of change. The warmth and plenty of the pub might be a hope of what was to come. The car, a symbol of the future, is parked unglamorously next to a horse and cart. As advertisements go, it’s very subtle: the word Dunlop appears only on the spare tyre on the back of the car.

Mumming plays are still performed in some parts of England. These folk plays originated in medieval times, but few were written down until the early years of the twentieth century. My father owned a book containing many of these plays. They are very primitive dramas and although every village’s version evolved over the centuries there is a recognisable pattern. After an induction promising a fine performance, two protagonists appear and once they have boasted of their bravery, fight a duel. One of them is wounded or killed, and a doctor is called who revives the fallen man. The performance usually ended with a song during which a collection was held. You can find more information at the English Folk Dance and Song Society.

Shakespeare knew these plays. His only, rather disparaging, reference is in the most unlikely of plays, Coriolanus (set in ancient Rome). The senator Menenius insults the people’s tribunes who “make faces like mummers”.

In the play from Great Wolford, Warwickshire, Father Christmas sets the scene:

In comes I old Father Christmas

In comes I to make the fun.

My hair is short my beard is long

And me hat’s tied on with a leathern thong.

A room a room brave gallants all

Give us all room to rhyme

And we’ll show you some good activity

This merry Christmas time.

Activity of age activity of youth.

The book, The Mummers’ Play, was published posthumously by friends and former colleagues of Reginald Tiddy, a lecturer in English and Classical Literature at Oxford University who died on active service in France. In a strange coincidence Tiddy died in 1916, 300 years after Shakespeare, and his book was published in 1923, 300 years after Shakespeare’s Folio had been published, also by his friends and former colleagues.

The picture’s a reminder of tradition, the present realities of war and the importance of social cohesion, while the Mumming plays are about life, death and renewal. Both celebrate the turning of the year, the remembrance of the past and optimism for the future.