A few days ago I was in a car travelling along a main road near Stratford-upon-Avon when a bird shot across the road then continued to fly alongside it at the bottom of the hedgerow, at the same speed as the car, perhaps 40mph. It was a real Earthflight moment without the need for microlites, gliders or silent drones. This magical view of the bird in flight went on for about 10 seconds, and was all the more special because it was a wild male sparrowhawk.

A few days ago I was in a car travelling along a main road near Stratford-upon-Avon when a bird shot across the road then continued to fly alongside it at the bottom of the hedgerow, at the same speed as the car, perhaps 40mph. It was a real Earthflight moment without the need for microlites, gliders or silent drones. This magical view of the bird in flight went on for about 10 seconds, and was all the more special because it was a wild male sparrowhawk.

Sparrowhawks are some of our smallest and commonest birds of prey. It’s some years now since I had another encounter with a female sparrowhawk which was found, dead, but quite perfect, at the bottom of our suburban garden. It had probably broken its neck while chasing a small garden bird. It was a rare privilege to be able to see it close up: the deadliness of its long, sharp talons and curved beak, the barred wing feathers which act as camouflage in woodland where the birds normally hunt.

These birds were common in Shakespeare’s day when like other birds of prey, they were kept for hunting. Hawking was a popular pastime, and different birds were flown by different ranks in society. The following list in the Boke of St Albans, dating from around 1486 is probably not meant to be taken literally, but suggests the suitability of birds for people of all ranks from rulers right down to knaves.

An eagle for an Emperor, a gyrfalcon for a King,

a peregrine for a prince, a saker for a knight,

a Merlin for a Lady, a goshawk for a yeoman,

a sparrowhawk for a priest, a musket for a holy water clerk,

a kestrel for a knave.

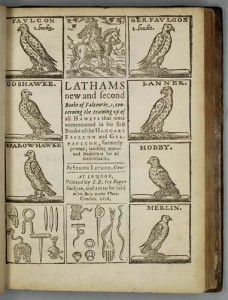

Many of these birds are illustrated on the title page of Latham’s 1615 Book of Falconrie. If you’re interested in stunning bird photography, take a look at the RSPB’s website.

Here’s a link to an article about the history of hawking by Richard Grassby and another to a page of Shakespeare references to the sport.

The Royal Shakespeare Company is about to mount a new production of The Taming of the Shrew, a play in which Shakespeare makes a connection between a man’s attempt to tame his wife and the training of a hawk. It’s not by any means his only reference to the sport, but it is the most obvious. There have been calls in recent years for the play not to be performed, so distasteful does this seem to us, but in many of the contemporary stories of wife-taming, the husband usually administered violent beatings. Petruchio’s attempt “to kill a wife with kindness” is comparatively mild, because it was well known that training a bird of prey could not by done by cruel means.

My falcon now is sharp and passing empty,

And till she stoop she must not be full-gorg’d,

For then she never looks upon her lure.

Another way I have to man my haggard,

To make her come and know her keeper’s call.

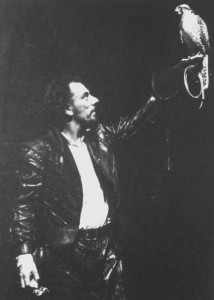

In the 1982 RSC production Alun Armstrong, playing Petruchio, made sure nobody missed the point by delivering this speech while carrying a hooded bird of prey on his wrist. A murmur went round the auditorium as the audience realised the bird was real. As he gently removed the bird’s hood allowing it the freedom to look around everybody held their breath, an unforgettable theatrical moment.

Interesting; have been enthralled by falconry since I was small. 🙂 However; the shrew will tend to be hunted by the falcon , rather than tamed- so in terms of metaphor it might be worth rethinking the above. 🙂

Pingback: Portia’s Casket | Voices News for January 11 | The Shakespeare Standard

I used to love watching the falconry when I worked at Mary Arden’s House, and learnt a lot. It was interesting to see that having one of our birds up in the air would attract wild raptors. Steve Wright was brilliant at keeping visitors interested and excited, even French teenagers.

Sparrowhawks are amazing birds and it’s not surprising that so many of them die from broken necks, they really do live in the fast lane. If catching prey means flying at full speed into a brick wall, they will do it.

I saw that production- I fell for Alun Armstrong on the spot…

That would have been an interesting production to see. I’ve just discovered this blog and, as a Shakespeare buff but first and foremost a slave to falconry, am delighted to see these references.

Certainly the list in the Boke of St. Albans was not meant to be taken literally (I’ve spent much of my adult life trying to debunk this myth as a student and falconry historian!) but shows the depth of symbolism the sport held. Since certain species require certain types of terrain to be flown properly, it was, and is, the case that you fly the hawk which you can do full justice in terms of land to fly over and quarry availability. In much of Britain the goshawk would have been most suitable as it can be flown in enclosed country at mixed quarry (indeed the “Boke” is solely concerned with their training, and that of sparrowhawks, which must be significant when one considers how few people were literate when it was printed). By contrast the large falcons needed much more open space and were flown in ways which necessitated, for the most part, them being followed on horseback. However, the list you mention was effectively social imagery – an eagle is all but useless, despite its size, for falconry in all but the most restricted conditions – so does this say something of the Emperor? The rankings of falcons and hawks, classified according to contemporary views, also represents an analogy of the feudal system – though has little practical value. One must have a fairly detailed knowledge of the various species and their characteristics to appreciate this, which of course few of us do in modern times.

Incidentally, the sparrowhawk you saw whilst driving was using you as a “beater!” This has been observed many times. The “spar” realises that as your car passes down the lane, it disturbs suitable tasty small birds, and so matches its speed, as far as possible, to yours to mask its approach. If anything breaks cover, the hawk flips over the hedge and has a good chance of securing its next meal – or else lands on a post and resumes “still hunting” for potential prey until another four wheeled assistant comes along. A great example of adaptability to a man-made environment, and one which gives many people a rare chance to see a wild accipiter hunting.