The World Shakespeare Festival, which has just begun, is already opening our eyes to performances of Shakespeare from some of the most remote corners of the world. Nothing does more to prove that Shakespeare is the world’s dramatist than productions which originate in places where Shakespeare is, you would think, not on the cultural menu, and these productions often demonstrate the persistence and bravery of those involved.

The World Shakespeare Festival, which has just begun, is already opening our eyes to performances of Shakespeare from some of the most remote corners of the world. Nothing does more to prove that Shakespeare is the world’s dramatist than productions which originate in places where Shakespeare is, you would think, not on the cultural menu, and these productions often demonstrate the persistence and bravery of those involved.

At the Swan Theatre in Stratford you’ll find Romeo and Juliet in Baghdad, set in modern Iraq where the usual feud between the Montagues and Capulets becomes the sectarian division between Sunni and Shia. The cycle of violence and revenge is fuelled by intervention from outside forces, which may make some of this production uncomfortable viewing.

But most of these zingy productions are happening as part of the Globe to Globe Festival in London. Here will be The Two Gentlemen of Verona from Zimbabwe, and Cymbeline by the South Sudan Theatre Company. The Republic of South Sudan became the world’s newest country in April 2011 after 50 years of violent struggle. Cymbeline‘s a play which examines the nationalistic desire of a small country to liberate itself from external powers. The resulting adaptation draws on local traditions to create a show that resonates with the politics and celebrates the traditions of South Sudan.

But the most unlikely company visiting the Globe must be Roy-e-Sabs, from Afghanistan. They have been described as “a theatrical miracle”. In 2005 they performed Love’s Labour’s Lost in war-ravaged Kabul. Controversially, men and women acted together, the women sometimes not wearing headscarves, and lovers held hands, all of which had been strictly forbidden. It’s truly amazing that this group are now bringing a new production of The Comedy of Errors to London.

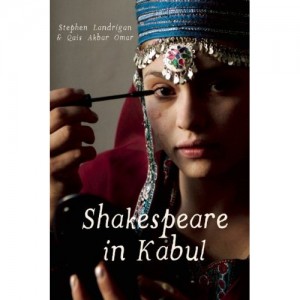

The story of the 2005 production of Love’s Labour’s Lost that took place in Kabul is told in a new book, Shakespeare in Kabul. On 26 April the authors, Stephen Landrigan and Qais Akbar Omar, are talking at the Shakespeare Centre in Stratford-upon-Avon as part of the Stratford Literary Festival. It’s a fascinating story, beginning with the difficulties of translating the play, and the problems of finding actors since theatre is not part of Afghanistan’s culture. Unexpected barriers were encountered: some of the actors could barely read, for instance. Several of the actors had been wounded themselves, or had seen relatives killed. And they had to overcome the fact that a woman on stage is still thought no better than a prostitute. The play was adapted and directed by the French actress Corinne Jaber for a local audience and taking their sensibilities into account, so the young men, played as nobles of Kabul, disguised themselves as itinerant Indian dancers rather than Russians.

The story of the 2005 production of Love’s Labour’s Lost that took place in Kabul is told in a new book, Shakespeare in Kabul. On 26 April the authors, Stephen Landrigan and Qais Akbar Omar, are talking at the Shakespeare Centre in Stratford-upon-Avon as part of the Stratford Literary Festival. It’s a fascinating story, beginning with the difficulties of translating the play, and the problems of finding actors since theatre is not part of Afghanistan’s culture. Unexpected barriers were encountered: some of the actors could barely read, for instance. Several of the actors had been wounded themselves, or had seen relatives killed. And they had to overcome the fact that a woman on stage is still thought no better than a prostitute. The play was adapted and directed by the French actress Corinne Jaber for a local audience and taking their sensibilities into account, so the young men, played as nobles of Kabul, disguised themselves as itinerant Indian dancers rather than Russians.

But the major hurdle was the political situation. There can be no country in the world with a more troubled history than Afghanistan. In 2005 there was a feeling of optimism: “the future held no limits, the actors believed”.

The production was received with rave reviews from foreign journalists and the cheers of local audiences. But just as in the play, the end was tinged with sorrow. Recently that hope for the future of Afghanistan has turned to fear of what may happen when the peacekeepers depart. Love’s Labour’s Lost ends with the possibility that a resolution will be found in time, and this hope can still be seen with the visit of the company to London with another Shakespeare play. Perhaps the choice is significant: The Comedy of Errors is a play in which the happiness promised in Love’s Labour’s Lost becomes a reality, all disputes ended and families reunited.

Reactions to all of these productions will form part of the new project Shakespeare’s Global Communities. Look out for its official launch.

I’m so glad you’ve written this post Sylvia. It’s striking and sad that, 400 years after the Elizabethans considered acting an unsuitable job for a woman, it is still the same in Afghanistan.

Woman’s Hour did a piece on the Globe’s Afghan Comedy of Errors on Tuesday. Rehearsals took place in India because of the risks in Kabul but the piece is on a reporter going to Kabul to talk to Corinne Jaber and some of the participants during the early auditions.

Corinne Jaber has reset the play in contemporary Afghanistan – she talked about how the family ties and cultural codes in the play have a meaning there today. She couldn’t advertise auditions so actresses had to be sought by word of mouth. The reporter said that actresses told her that they were harassed, insulted and even received death threats because of their work. One of the actresses spoke about how the play resonates for her – she said she felt the story had been written specifically for Afghanistan and that the scene where Adriana is waiting for her husband to come home was written for an Afghan woman. Shakespeare “seemed to understand me as a woman better than I do myself”. You can listen to the piece again at http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01gg7cl#p00rfjjv (scroll down towards the bottom of the page and click on Chapter 2).

I hope the audiences at the Globe next month appreciate what it has taken to stage the play. Who says Shakespeare is just a dead poet!

Thanks for your message with this additional information. I agree, this production should have special resonance when it’s performed at the Globe.

Pingback: Carnivalesque #84 « Conversion Narratives in Early Modern Europe

Great post! Do you, by chance, know if there are any other documentaries (like Shakespeare from Kabul) about any of the other troupes that are taking part in the festival?

I’m afraid I’ve not heard of any programmes about the rest of the Globe to Globe festival. I would think Shakespeare’s Globe would know: they have a library and archive so you might try asking them.