Last week I attended a lecture in which the speaker said, with a laugh, that according to Stephen Greenblatt and others Shakespeare left Stratford in order to get away from his wife. I bristled. Why, when it wasn’t relevant to the subject of the lecture, did he make a joke at Anne Hathaway’s expense?

As it happens, I’m currently reading Germaine Greer’s book Shakespeare’s Wife, and while she probably overstates her case, given the awful press that Anne has had over many years I agree it’s about time someone stood up for her. Most biographies of Shakespeare have lazily accepted the received prejudice against her without bothering to look deeper.

Greer has uncovered much material suggesting that married women were more than capable of running homes and businesses on their own, and towards the end of her book, “the intrepid author makes the absurd suggestion that Anne Shakespeare might have been involved in the First Folio project”, and she goes on to state “The idea that she might be entitled to some of the credit for the preservation of her husband’s work is apparently too ridiculous to contemplate, which is why we shall now contemplate it”.

So how did this prejudice start? Early accounts of Shakespeare’s life didn’t mention any disharmony, or suggest there was anything unusual in a husband working away from home. But the discovery of the will and its infamous legacy of the “second best bed” didn’t help, and neither did the marriage bond and baptism record which indicated that the wedding might have been rushed because Anne was pregnant. The already-known facts that Anne was several years older than William, and that the couple had only three children, only blackened her image even more.

Commentators are always happy to suggest that in Twelfth Night Orsino’s suggestion that a woman should marry a man older than herself is a swipe at Anne, without also noting that several of Shakespeare’s young heroines, Rosalind, Imogen and Helena in All’s Well That Ends Well are considerably more emotionally and possibly physically mature than their chosen partners.

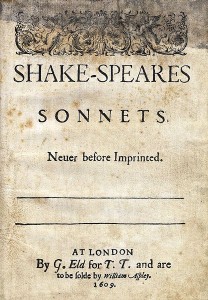

Then, of course, there’s the “evidence” in the Sonnets. No area of Shakespeare’s work has generated the speculation surrounding these 154 poems. Most serious editions, like Kathryn Duncan-Jones’s Arden, don’t countenance any personal interpretations, but questions still have to be asked about when and why they were written. Even such sensible commentators as Paul Edmondson and Stanley Wells have to admit that the “story” if there is one, is very complicated. Contemporary references that help to date the poems are sought because the story seems, in some sense, to have to be true.

The story that’s usually uncovered is of Shakespeare’s love for a young man, an affair with a dark lady, and sometimes a rival poet. But some sonnets don’t fit. Sonnet 145 is usually dismissed as an immature poem, and in the past some have even suggested that Shakespeare didn’t write it. It’s the one which puns on Anne’s maiden name, and is one of the tenderest of the poems. It ends:

“I hate” from hate away she threw

And saved my life, saying –“Not you”.

Another sonnet which is mentioned grudgingly if at all in biographical terms is Sonnet 33, where Shakespeare puns on the words sun/son. “My sun one early morn did shine”. Read in the light of other uses of the word “sun”, for example where Hamlet is “too much in the sun”, and in Henry VI part 3 where the sons of York see “three glorious suns” which prophesy the unity of their family, this poem makes sense if it’s seen to be about the death of Shakespeare’s own son.

Sonnet 135 and Sonnet 136 both pun on Shakespeare’s name: “My name is Will”. These personal poems are scattered throughout the sonnets. In trying to make sense of the sequence in which love is directed towards the boy or the dark lady, have interpreters ignored the fact that some of them could have been written to Anne? Reading them on their own, there’s no reason that Sonnet 57 couldn’t be addressed to her, and Sonnet 117, below, reads like an apology to a wife:

Accuse me thus: that I have scanted all

Wherein I should your great deserts repay;

Forgot upon your dearest love to call,

Whereto all bonds do tie me day by day;

That I have frequent been with unknown minds,

And given to time your own dear-purchased right;

That I have hoisted sail to all the winds

Which should transport me farthest from your sight.

Book both my wilfulness and errors down,

And on just proof surmise accumulate;

Bring me within the level of your frown,

But shoot not at me in your waken’d hate;

Since my appeal says I did strive to prove

The constancy and virtue of your love.

For all we know, one of the stories told by the sonnets is of Shakespeare’s love for his wife. It’s at least as good a story as the one which biographers have written over the past hundred and fifty years, and may be closer to the truth.

The new novel by Jude Morgan, “The Secret Life of William Shakespeare” presents a beautifully nuanced portrait of Anne and imagines a loving and supportive relationship between her and Will. It’s coming out in Britian in September but you can read the reviews, which have been overwhelmingly positive, on Amazon. Adele Geras, whose opinion on matters literary and historical I greatly respect, thought it was excellent – check her website for a review.

Thanks Sylvia, it’s about time someone stood up for Anne. I agree that Greer’s book is overstated, but there is no factual basis in the speculation that Shakespeare and his wife were estranged. Men had to leave their homes and work away, as they do today, but then it was much more difficult to visit often. Just because letters don’t exist doesn’t mean they didn’t write.

Hi Sylvia!

Thank you so much for your lovely article.

I am so happy that you brought up this subject. It really seems that all of these scholars who think Shakespeare’s was a loveless marriage are looking at the glass as half empty.

It also seems to me that all of the evidence to suggest that they did not love each other, whether it’s the will leaving her with the second-best bed, the so-called rushed marriage, no surviving letters between them, and so on, is really a lack of evidence.

I like to think that the absence of evidence does not mean that there is evidence of absence. I think that just because we do not know that Shakespeare loved his wife, does not mean they did not love each other. I am convinced that theirs was a strong and happy marriage.

By the way, if you have time, I recently posted a question about this exact subject on the LinkedIn Shakespeare Forum. I think you will find the responses entertaining, and I think you would be delighted to know that there was a strong consensus in defense of Anne Hathaway!

Thank you again, and I hope you have a wonderful day!

Cheers,

David Schajer

Unfortunately, I bristle at the mere mention of Germaine Greer; the kind of person who looks as if she eats young, female scholars for breakfast…! I find her insufferable and every single thing she writes or says is tainted beyond recall by her obsessive feminism- which is an anachronism in any case in relation to seventeenth century history. Of course women made significant contributions to culture, society and the economy in C17, everybody knows that without the assistance of Germaine Greer (!) and those contributions are worthy of greater recognition than being reduced to grist for a postmodern feminist mill.

…substitute c16 for c17 wherever it appears above…