Last week Stratford’s Shakespeare Club was lucky enough to be given a look into internationally-renowned director Michael Attenborough’s views of Shakespeare.

Last week Stratford’s Shakespeare Club was lucky enough to be given a look into internationally-renowned director Michael Attenborough’s views of Shakespeare.

Attenborough is currently Artistic Director of the Almeida Theatre in London, though he is resigning from that post after ten years or so in the spring.

He’s shown himself to be an extremely able administrator during that time, but his reason for leaving is that he wants to concentrate on directing, and one of his opening remarks was that he would be interested in directing for the RSC again. (Yes please!) For ten years he was associated with the RSC, first as Resident Director and Executive Producer, later becoming Principal Associate Director of the Company.

He began by talking about this period, and how when he first worked with the RSC he avoided directing Shakespeare until he knew how he wanted to do it. The non-Shakespeare plays he directed included The Changeling at the Swan, and premieres of After Easter and The Herbal Bed at The Other Place. His first Shakespeare with the company was the 1997 production of Romeo and Juliet with Ray Fearon and Zoe Waites in the Swan Theatre which went on international tour and led to the 1999 production of Othello in the Royal Shakespeare Theatre with the same two leads. Later he directed Henry IV parts 1 and 2 in the Swan with Des Barrit playing Falstaff for the first time.

He suggested that even without Shakespeare we would still be fascinated by the writing of the Elizabethan and Jacobean period. Shakespeare was one among many outstanding creative writers, and Attenborough suggested that it was the uncertainty of the times which led to this richness. Questions were being asked about the authority of the monarchy, about religion, and with the possibility of people from humble backgrounds changing their lives. The overriding question was “What does it mean to be a man?”, a question Shakespeare explores over and over again, most memorably in Hamlet.

Theatre was a new phenomenon, providing places where these questions could be investigated in public, and drama evolved so that opposing views could be set out and discussed. Blank verse captured the energy of human speech and the writers used it to create easily-remembered speeches in which actors could move from thought to thought. Earlier plays gave people certainty: the plays of Shakespeare’s time dealt in uncertainly. Attenborough’s phrase was “man is the unity of opposites”. He took Falstaff as his example: a man who is full of contradictions and extremes, a real human being.

It was clear his great love is for working with actors in the rehearsal room, and in particular working on Shakespeare’s words. At the start of Henry IV Part 2 the audiences is commanded to “Open your ears”. He suggested we should look for the “opposites”, what John Barton calls the “antithesis” in speeches and situations. When Hamlet asks “To be or not to be, that is the question”, the question is not answered, but the play happens around it.

He described the work of the director as directing the energy of the actors. In Shakespeare when a character speaks he is given the best possible words available to that character to get what they want. Something is always at stake, no matter how trivial the speech seems. The actor’s job is to ask themselves “What do I want and why have I chosen these particular words?”. Ownership of the words is the key, so there is no gap between the character and the words.

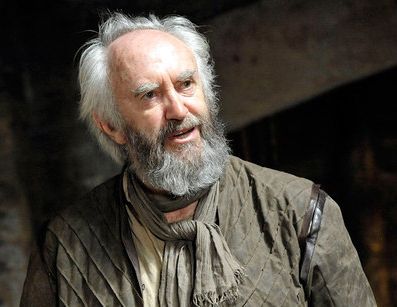

He has most recently directed Jonathan Pryce’s King Lear at the Almeida. After speaking for an hour (entirely without notes) he left us with the suggestion that later on we should look at one speech from King Lear that exemplifies the idea of opposites. It’s not a major speech, and can get overlooked among the turbulence of the first major scene of the play. It’s the King of France’s speech towards the end of Act 1 Scene 1 when he accepts Cordelia despite her father’s rejection, and the Duke of Burgundy’s refusal to marry her without a dowry:

Fairest Cordelia, that art most rich, being poor;

Most choice, forsaken; and most lov’d, despis’d!

Thee and thy virtues here I seize upon.

Be it lawful I take up what’s cast away.

Gods, gods! ’tis strange that from their cold’st neglect

My love should kindle to inflam’d respect.

Thy dow’rless daughter, King, thrown to my chance,

Is queen of us, of ours, and our fair France.

Not all the dukes in wat’rish Burgundy

Can buy this unpriz’d precious maid of me.

Bid them farewell, Cordelia, though unkind.

Thou losest here, a better where to find.

Sylvia, it’s great to hear a director talking about words. So many actors speak Shakespeare in lines (rushing to get to the end of each one) rather than in words (relishing the sound & meaning of each, and distributing emphasis appropriately), when one of the wonderful things about verse like Shakespeare’s is the ability of individual words to create dramatic tension and expand the field of meaning through opposites & multiple senses!