More than any other holiday time, Christmas has always been about food and drink. Thomas Tusser, an East Anglian farmer, wrote his verse calendar of the year Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry, published in 1557 and still full of delight in spite of his quirky and occasionally painful rhyming descriptions of rural life. For Christmas-time Tusser wrote a whole series of poems celebrating the birth of Christ and the importance of charity at this time of year. One ends:

What season then better, of all the whole yeere,

thy needie poore neighbour to comfort and cheere?

Another poem is headed: Christmas husbandlie fare and goes like this:

Good husband and huswife now cheefly be glad,

things handsom to have, as they ought to be had;

They both doo provide against Christmas doo come,

to welcome good neighbour, good cheere to have some.

Good bread and good drinke, a good fier in the hall,

brawne, pudding and souse, and good mustard withall.

Beefe, mutton, and porke, shred pies of the best,

pig, veale, goose and capon, and turkey well drest;

Cheese, apples and nuts, joly Carols to heare,

as then in the countrie is counted good cheare.

What cost to good husband is any of this?

good houshold provision onely it is.

Of other the like, I doo leave out a menie,

that costeth the husbandman never a penie.

For Tusser the plenty of the Christmas feast is the result of good husbandry, farmers having put aside enough of their produce to see them and their less fortunate neighbours through the holiday season.

About fifty years later Elinor Fettiplace, wife of Sir Richard Fettiplace from Appleton Manor in Oxfordshire wrote her “Receipt” or recipe book. As befits a higher-status home, her ingredients are more exotic and expensive. Guests are offered going-home presents of sweetmeats and fancy biscuits, and marchpane (marzipan), richly decorated, was the centre piece of the feast.

Even so, Hilary Spurling who edited Fettiplace’s book, commented that in the recipes you can detect “traces of the medieval origins of English cookery – all the standard ingredients (except the roast potato) of a conventional Christmas dinner”.

One item not on the menu for Tusser, but present in Fettiplace, is the plum pudding, rich in imported ingredients. This is Fettiplace’s recipe:

One item not on the menu for Tusser, but present in Fettiplace, is the plum pudding, rich in imported ingredients. This is Fettiplace’s recipe:

For a Christmas pudding:

Take twelve eggs and break them, then take crumbs of bread, and mace, and currants, and dates cut small, and some ox suet small minced and some saffron, put all these in a sheep’s maw and so boil it.

Spurling suggests it would take up to 6lb of fruit and would make enough pudding for 40 people. Rather than a sauce based on milk or cream which would not have been available at this time of year it would have been served with butter and sugar creamed with sack (sherry). Even without sugar the fruit would have made the pudding very sweet.

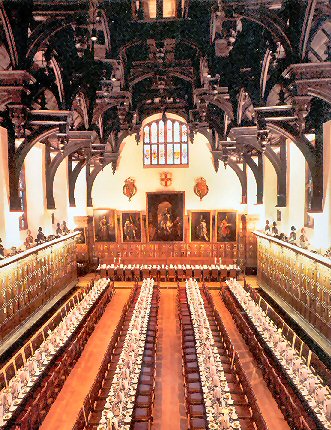

Going even further up the social scale, it is said that Queen Elizabeth herself made a Christmas pudding for the lawyers of the Middle Temple. The story goes that she gave them the twenty-nine- foot long Bench Table which still stands in Middle Temple Hall. Middle Temple Hall was renowned for its Christmas-time celebrations, with Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night being performed there in 1602. The table was made from an oak tree from Windsor Great Park whose planks had had been sailed down river especially for them, and the first pudding was mixed on this very table. A small amount of this pudding was saved to be mixed in the following year, and this tradition continued until 1966 when it died out until revived by the Queen Mother in 1971.

This tradition of things being handed on in n unbroken line is very reminiscent of the Yule log (and even the Olympic torch). The Yule log must have been more of a tree, as it burned throughout the twelve days of Christmas. At the end of the holiday period a piece was kept which was used to light the Yule log for the following year. Today the only Yule log most of us will get to see is a chocolate cake decorated with icing and a sprig of artificial holly!