Shakespeare is now so universally known, his reputation so unassailable, we naturally wonder how he was received during his own lifetime. Did his contemporaries realise that he would be remembered and celebrated centuries afterwards?

Shakespeare is now so universally known, his reputation so unassailable, we naturally wonder how he was received during his own lifetime. Did his contemporaries realise that he would be remembered and celebrated centuries afterwards?

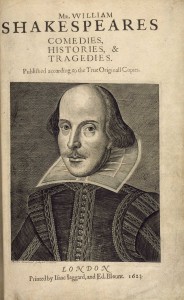

This was the question, subtitled “What did they make of him then?” that Roger Pringle strove to answer at last week’s meeting of the Stratford Shakespeare Club. He looked specifically at the period up to 1623 when Shakespeare’s collected plays were published posthumously in the First Folio.

It’s commonly assumed that his contemporaries, although they acknowledged his talent, didn’t recognise his true value, regarding him as one fine writer among many. This assessment may be an attempt to redress the balance which usually undervalues his fellow-writers such as Marlowe, Jonson, Webster, Fletcher and many others. It has been said that even without Shakespeare the period of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries would still be known as the greatest flowering of English writing in history.

Roger Pringle looked at the wide range of evidence available to try to assess how Shakespeare was viewed in comparison with his contemporaries. Some of the assessments were unflattering, like the first reference we have, Robert Greene’s scathing attack on the “upstart crow”, an actor who thinks himself as good as the university writers. It’s obviously the result of professional jealousy, but also gives us some insight into how Shakespeare was being perceived right at the beginning of his writing career.

Later assessments of his personality were more flattering: by this time Shakespeare himself was successful and in a position of some power himself, but the adjectives that tend to be used are “honest”, “sweet” and “gentle”.

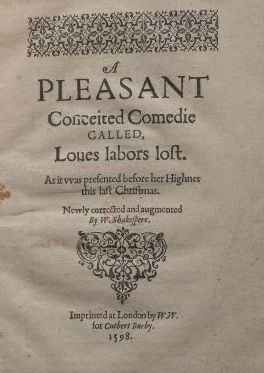

The title page of the quarto for Love’s Labour’s Lost, the first play to recognise Shakespeare as author

Pringle examined the record of publications to demonstrate the relative popularity of Shakespeare’s work. Half of Shakespeare’s plays were published in cheap quarto editions, several of them in more than one edition. It was the printer, not the author, that published the plays so they would only have been printed if they were expected to make a profit. By 1616 forty-five editions of Shakespeare’s plays had been published, no other writer getting near this number. His growing reputation can be judged by the fact that his name began appearing on the title page of his plays in 1598, and of the 29 subsequent publications 21 were under his name. And publishers began falsely attributing work to Shakespeare because his name sold, as can be seen in The Passionate Pilgrim in 1599.

His most popular publication was the love poem Venus and Adonis, published eight times in his lifetime, while The Rape of Lucrece was published six times. In the Cambridge University Parnassus Plays one character says he will sleep with Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis under his pillow.

In terms of performance, Shakespeare’s plays were popular with the crowds who visited the open-air playhouses, law students at the Inns of Court, both the Universities (Oxford and Cambridge) and at court. This popularity went right to the top. In 1605 The Merchant of Venice was performed before the King who enjoyed it so much he commanded a repeat performance. And Shakespeare’s popularity lasted over twenty years, an extraordinary record.

Pringle also examined how influential Shakespeare had been on his peers. Was he, like Falstaff, not only witty in himself but the cause of wit in other men? He referred to conscious borrowings such as Marston’s quoting of Richard III’s line “A horse, a horse”, and to the number of quotations used in anthologies. In these Shakespeare is quoted more times than other writers. Some, like Marston above, were paying intentional compliments to Shakespeare, others were probably unconscious, showing how quickly his phrases became absorbed into everyday speech.

He reserved the clearest indications of Shakespeare’s value till last. Ben Jonson’s 80-line tribute in the First Folio illustrates how highly Shakespeare was regarded. Pringle describes this as “one of the finest occasional poems in the language”, and it’s full of memorable phrases such as “Soul of the age”, “Shine forth, thou star of poets”, “He was not of an age, but for all time!”, “Sweet Swan of Avon”. But more than just praising, Jonson confirms that Shakespeare was a good actor, that he was a likeable man, that he was a better writer than his contemporaries, and admired by both Queen Elizabeth and King James. He can’t resist a back-handed compliment with the line about Shakespeare having “small Latin, and less Greek”, but Jonson’s sincerity can’t be doubted. It may be that Jonson was unusually perceptive, but Roger Pringle’s conclusion was that even during his lifetime Shakespeare’s contemporaries were aware that he was something special.

Thank you for another intriguing post Sylvia. As the post concerns reputation, I hope my comments are relevant. I confess I’m only just starting to explore the Parnassus plays, and I expect that the points I raise have been made more cogently by others already. Nevertheless, the character Gullio – presumably a conflation of Gull and Gulielmus (William Shakespeare) – is a grand buffoon. Given that his dramatic role is to excite laughter, shouldn’t we take everything he says with, at the very least, a grain of salt, or – for maximum irony – as the opposite of what is sensible? It is he who says “O sweet Mr. Shakspeare! I’le have his picture in my study at the courte”. Gullio (like Greene’s depiction of Shakespeare) is a literary ignoramus and a plagiariser. He is wholly concerned with a false, aspirational presentation of himself – “I stood stroking up my haire, which became me very admirably…”. And of all the pantheon of Elizabethan poets, his hero is William Shakespeare. Shouldn’t be asking why the author/s chose Shakespeare for this questionable honour? If Shakespeare was unquestionably the greatest writer of the age, wouldn’t this be a rather “flat” choice for a comic writer? Wouldn’t the author/s choose for their literary buffoon, a second-rate writer as a hero – someone well-known known by the audience to be suspect? I’ve often seen this piece cited as evidence of Shakespeare’s reputation as a writer. Indeed it does seem to cast light on his reputation, but I can’t see how it’s a favourable light? What am I missing? Best wishes – Bruce.

Thanks for your comment! It’s difficult to know how, and how seriously, to take the Parnassus plays. I think the most signficant thing is not whether it’s meant to be flattering or critical, but the fact that Shakespeare is well-enough known to be the subject of a student joke, and that the audience would get the reference to him and his poem Venus and Adonis.