This week’s TV programme Countryfile was guest edited by the Prince of Wales, giving him the opportunity to explore issues about the countryside and farming that are close to his heart.

The prince is also a great lover of Shakespeare, who often wrote about the connection between the rulers of the land and those who work it. Shakespeare reminds us that kings are human too: on the night before Agincourt Henry V, in disguise, speaks to one of his soldiers. “I think the king is but a man, as I am: the violet smells to him as it doth to me:…” And when Richard II realises he has been abandoned by his allies, he lets the facade slip:

I live with bread like you, feel want,

Taste grief, need friends: subjected thus,

How can you say to me, I am a king?

At times of crisis Shakespeare’s kings often long for a simple life. Henry VI escapes from the height of battle:

O God! methinks it were a happy life,

To be no better than a homely swain;

To sit upon a hill, as I do now,

To carve out dials quaintly, point by point,

Thereby to see the minutes how they run,

How many make the hour full complete;

How many hours bring about the day; …

When this is known, then to divide the times: …

So many days my ewes have been with young;

So many weeks ere the poor fools will ean:

So many years ere I shall shear the fleece: …

Ah, what a life were this! how sweet! how lovely!

Gives not the hawthorn-bush a sweeter shade

To shepherds looking on their silly sheep,

Than doth a rich embroider’d canopy

To kings that fear their subjects’ treachery?

In King John, young Prince Arthur is an unwilling pawn in a power game being played by his elders:

…By my christendom,

So I were out of prison and kept sheep,

I should be as merry as the day is long.

References to the humble sheep have always abounded: in Greek legend, Jason sought the Golden Fleece, referred to in The Merchant of Venice, and everyone was familiar with the image of Christ as the Good Shepherd and the nativity story of the shepherds, the first to see the star that signalled his birth.

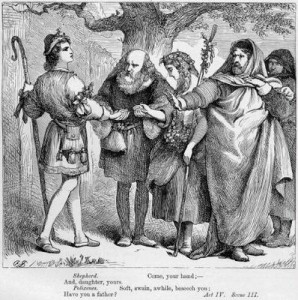

In Shakespeare’s own time poet Edmund Spenser popularised the literary convention of pastoral in The Shepheardes Calendar. He describes himself as a shepherd, spending his time playing music, in contemplation and writing poetry. Although Shakespeare plays with this convention in As You Like It, most of his references are much more down to earth. Corin, the shepherd, explains the practicalities of being a shepherd to Touchstone, the courtier:

Those that are good manners at the court are as ridiculous in the country as the behaviour of the country is most mockable at the court. You told me you salute not

at the court, but you kiss your hands; that courtesy would be uncleanly if courtiers were shepherds…. Besides, our hands are hard….And they are often tarr’d over with the surgery of our sheep; and would you have us kiss tar? The courtier’s hands are perfum’d with civet.

Both Shakespeare’s parents were from farming families, and Stratford’s prosperity depended on agriculture. There’s still a Sheep Street in the town, and the Shakespeares had shepherds living across the road in Henley Street. Shakespeare’s father, although primarily a glover, was also a significant dealer in sheep. To the south of Stratford lie the Cotswold Hills, one of the most important wool-producing areas in the country with their own breed of sheep. Shakespeare knew the practicalities of the trade: in Henry IV Part 2 Silence and Shallow discuss the price of sheep, and the Young Shepherd in The Winter’s Tale tries to calculate the value of his fleeces:

Let me see: every ‘leven wether tods; every tod

yields pound and odd shilling; fifteen hundred

shorn. What comes the wool to?

The most obvious references to sheep come in the sheep-shearing scenes in The Winter’s Tale and in the scenes in the Forest of Arden in As You Like It, but there’s also an extremely unfunny exchange about sheep and shepherds in The Two Gentlemen of Verona and in Henry VIII the king and his followers enter in disguise dressed as shepherds. Joan of Arc too is a shepherd’s daughter.

References to sheep, lambs, fleeces, wool and shepherds are to be found in almost all of Shakespeare’s plays and poems, almost whenever he needs an image of vulnerability. Before the mood darkens in The Winter’s Tale Polixenes remembers when he and Leontes were boys:

We were as twinn’d lambs that did frisk i’ the sun,

And bleat the one at the other: what we changed

Was innocence for innocence.

My favourite quotation, though, is the shepherd Corin’s simple but dignified statement of his philosophy:

Sir, I am a true labourer: I earn that I eat, get that I

wear; owe no man hate, envy no man’s happiness; glad of other

men’s good, content with my harm; and the greatest of my pride is

to see my ewes graze and my lambs suck.

Personally, I would happily see the POW abandon the privileges of monarchy to live as his ‘subjects’ do…! 🙂 rather than playing at it for the benefit of national television…