What is the ideal theatre, or stage, for Shakespeare? It’s a question that theatre people have been addressing for centuries. Shakespeare didn’t write exclusively for the Globe, and even though it was purpose-built by Shakespeare’s company in 1599 I don’t suppose it was regarded as perfect. Shakespeare had other spaces in his mind: the indoor Blackfriars, venues like Middle Temple Hall and halls in royal palaces.

Shakespeare’s Globe has always aimed to have an indoor theatre, and the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse is currently under construction. When it opens in early 2014 it’ll give the opportunity “to investigate indoor theatre practice and to stage Jacobean plays in their intended atmosphere”. Controversially, it will be candlelit. It won’t be an exact replica of the Blackfriars because as with the Globe, nobody has the plans.

It’s interesting to see how much ideas about theatre spaces have changed in recent decades. In 1932 the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre was opened with the hope that it would be the best theatre for Shakespeare in the world.

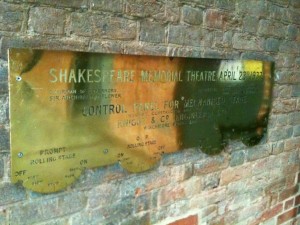

Attached to the wall just round the corner from the dock doors that allow sets onto the backstage area of the Royal Shakespeare Theatre is a brightly-polished brass plate. It is in part a commemorative plaque for the theatre itself, but when it was in its original location in the wings it was also functional: it controlled the theatre’s state of the art mechanised stage.

Attached to the wall just round the corner from the dock doors that allow sets onto the backstage area of the Royal Shakespeare Theatre is a brightly-polished brass plate. It is in part a commemorative plaque for the theatre itself, but when it was in its original location in the wings it was also functional: it controlled the theatre’s state of the art mechanised stage.

The architect and engineers wanted to create an emphatically different atmosphere from existing theatres. The barrier in Victorian theatres was seen to be that elaborate scene changes meant long breaks between scenes and often the rearrangement of the order of scenes. It was in order to create swifter, even seamless changes of scene while retaining the spectacle, that the innovations were made to the SMT’s stage.

There had been experiments, led by William Poel, with simpler staging closer to Shakespeare’s, but the Director Bridges-Adams insisted on having a theatre with a proscenium arch and the potential for elaborate scenery, though it would also allow a range of styles and types of performance. Reading statements from the time of the opening in 1932, it’s apparent that the builders of the theatre were mightily proud of the mechanical achievements of the new building.

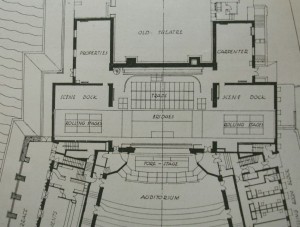

As shown on the brass plate, the mechanised stage consisted of two parts: the rolling stages and bridges. The rolling stages could be set up, one on each side of the stage, with a different set on each. Each was on wooden sleepers and rolled on rails, powered by electric winches. The Architect and Building News described the effect:

“a complete scene may be set in advance and rolled on in place of the preceding scene, the time being occupied for a complete change being about 25 seconds. Each rolling stage is equipped with traps, and …the two rolling stages may be coupled together to form one continuous stage”.

The two bridges enabled sets the width of the stage to be raised or lowered from below to the stage level or above it. At the back of the stage was hung a massive cyclorama, a plaster surface onto which different colours and effects could be projected, and which could be brought forward 20 feet. And there was a traditional fly tower from which elements of set could be brought down.

But the theatre did not get off to a good start. In her book The Royal Shakespeare Company: a history of ten decades Sally Beauman describes the theatre’s opening as an unremitting disaster, including the mechanised stage. But many of the problems were caused by planning failures rather than the theatre itself. Even on that first day, but not while the press of the world were there to see it (they left at the first interval of Henry IV part 1), the rolling stages scored a success when, joined together, they were used for the coronation procession at the end of Henry IV part 2.

The actors were said to have had difficulty making themselves heard, but later in the season the same actors appeared in a triumphant production of The Merchant of Venice directed by the flamboyant Russian director Theodor Komisarjevsky who used every trick the theatre was capable of. The stage became a star, the scene changes from Venice to Belmont and back again being entertaining in themselves and helping the actors by setting a mood for the scenes.

There were of course difficulties. Technical hitches meant the stages often stuck, though this is not exactly a phenomenon unknown to other theatres. The rolling stages behind the proscenium arch ensured that much of the acting took place upstage, increasing the gap between the actors and audiences. This distance was actually increased by the sizeable forestage.

It couldn’t be said that the audience had been forgotten: the view of the stage was unobstructed, the acoustics had been tested scientifically, and the seats were comfortable. But the control plate in theStratfordtheatre is perhaps a reminder that what the audience really needs is a human connection rather than the latest technical wizardry. Fortunately this is not likely to be an issue in the intimate new theatre, seating only 350, that’s currently being built in London.