It’s hard, indeed impossible, for us to imagine what it would be like to live without a clear idea of the world outside our own immediate locality. But many people of Shakespeare’s period might never have seen what we would call a proper map. Laurence Nowell’s map of the British Isles was published in 1564, and Christopher Saxton’s map of Warwickshire appeared in 1576. And these maps, as well as earlier manuscript maps, would have been seen by only a fraction of the population.

Shakespeare, obviously, was familiar with maps. In Henry IV Part 1 the rebels look over a map and discuss how they will divide land between themselves, and in the same vein, in King Lear, the map begins the very real fracturing of the country that follows its division. Onstage it’s quite common for the map to be torn apart as the play progresses, and as the inner world of the characters falls apart. Then of course there is the lovely section of The Comedy of Errors where one of the characters is described as “spherical, like a globe”, and two characters proceed to bawdily “find out countries in her”.

Maps were seen as factual, so symbolically honest. In Henry VI Part 2, the king exclaims:

Ah, uncle Humphrey! in thy face I see

The map of honour, truth and loyalty

But maps were mostly about power, not about travel. Queen Elizabeth 1, in the Ditchley Portrait, stands with her feet firmly planted on a map of her kingdom. Nowell’s map was made not to help people move around the country, but on the command of Elizabeth’s first minister, William Cecil, who is supposed to have carried a small version with him at all times.

Some clues about how people communicated are to be found on this site, a history of the postal service that includes a map of the network of post roads during Shakespeare’s lifetime and describes the structure that ensured the delivery of items sent by post.

Maps became common enough for jokes to be made about them: in Twelfth Night, Malvolio is said to:

smile his

face into more lines than is in the new map with the

augmentation of the Indies:

a reference to Mercator’s map of around 1592.

Our modern obsession with maps has resulted in many online resources, and the rest of this post is going to expand on some of those which I’ve recently discovered and been intrigued by. The most comprehensive is Old Maps Online, a collaborative project that does what it says on the tin. It’s easily searchable through a map of the world, and includes a timeline. There’s a review of the site here.

Another treasure-trove of map images, which provided several of those reproduced here, is the Library of Congress. Both these projects demonstrate through maps the development of scientific knowledge about the world during Shakespeare’s time, when the ancient Ptolemaic system, in which the earth was at the centre of the universe, gave way to Copernicus’s discovery that the planets revolve around the sun.

If you’re interested in finding out more about early maps you might like to check out the British Library’s map project in which members of the public can link old maps with online ones by a process called Georeferencing.

And here’s a project I heard about just as I was writing this piece. Tate Gallery’s Art Maps project aims to get people to help locate exactly where paintings were made. The website claims:

It also will allow people to record and share their memories and emotional or creative responses to the places associated with the artworks in ways that will generate learning experiences and create new communities.

Sounds fascinating, do take a look.

For those of you who like a mystery, you might like this story about the Vinland map. This manuscript map appeared to show that the Vikings had discovered America before Columbus. It was found in the 1950s and in 1965 experts dated it to around 1440. It’s authenticity has always been in question, but what is particularly pleasing about this story is that it’s an amateur researcher who has done some sleuthing, following up early records of the documents of which this is a part, and found no mention. It looks like the Vinland map is a clever fake.

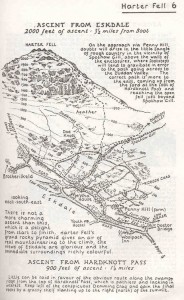

While we’re thinking about handmade maps, the Guardian recently ran a piece on why hand-drawn maps are back in the picture. With their personal associations, they warm our hearts just as any other recollection of a favourite place. My favourites are the delicate walking maps, part of Alfred Wainwright’s multi-volume Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells, each one a perfect combination of the aesthetic and the practical, and a labour of love.

And this link is to a new book telling the story of our infatuation with maps from Ptolemy onwards. Will people ever have the same feelings for a sat nav? I somehow doubt it.

Many thanks for posting this blog on one of my favourite subjects. In the 17 th century it was the Dutch who were the greatest map makers turning them into huge works of art, indeed one of Vermeer’s paintings shows a large and detailed map on the wall of his interior.