The current television series The White Queen has been criticised for its historical inaccuracies, its glossy costumes and out-of-period settings. I haven’t read the books by Philippa Gregory, so can’t tell how much of this relates to them and how much is just the TV series. But Gregory has been given two documentaries to explain, like a theatre programme might, her premise that the women she portrays are at least as interesting as the men, and maybe more, using the only weapons they could: cunning and patience.

The period covered by the series, roughly the 1460s to 1485, is familiar to most of us only through Shakespeare’s plays. And as is endlessly pointed out, the history Shakespeare gives us is not “true”. The notes and introductions to the editions of Henry VI Part 3 and Richard III which I have are mostly taken up by pointing out Shakespeare’s historical inaccuracies. Not only does Shakespeare rely on sources which promote the official Tudor view of the period, but he also twists facts, telescopes events and omits details. The success of his plays does not depend on facts, but on their compelling, irresistible drama.

Gregory’s White Queen is the wife of Richard’s eldest brother Edward, Elizabeth Woodville, fiercely protective of her children for whom she fights against the scheming nobles. All three of the most important women in the series; Elizabeth, Anne Neville and Margaret Beaufort are motivated by ambition for their families as much as for themselves.

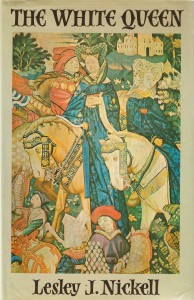

But hers isn’t the only fictionalised version of the story, and I have a copy of an earlier novel, also called The White Queen, that tells the story of Anne Neville. It’s written by Lesley Nickell, who I met in 1979 a year after she had achieved the considerable feat of getting her novel published by Bodley Head. Like Gregory, Nickell challenges the Shakespearean view of Richard, Duke of Gloucester as a vicious monster, making him a hero and his marriage to Anne Neville a love match. Nickell’s Anne is a helpless pawn, whereas Gregory’s Anne is spunkier, but otherwise the stories are similar. As Nickell, who sadly died earlier this year, points out in a note to her book, “[Anne’s] life is not well documented, except as an adjunct to other people’s schemes or actions. No evidence remains of her own opinion of the career which was thrust upon her”. In other words, it’s anybody’s guess, and writers from Shakespeare onwards have been free to imagine her thoughts and feelings.

But hers isn’t the only fictionalised version of the story, and I have a copy of an earlier novel, also called The White Queen, that tells the story of Anne Neville. It’s written by Lesley Nickell, who I met in 1979 a year after she had achieved the considerable feat of getting her novel published by Bodley Head. Like Gregory, Nickell challenges the Shakespearean view of Richard, Duke of Gloucester as a vicious monster, making him a hero and his marriage to Anne Neville a love match. Nickell’s Anne is a helpless pawn, whereas Gregory’s Anne is spunkier, but otherwise the stories are similar. As Nickell, who sadly died earlier this year, points out in a note to her book, “[Anne’s] life is not well documented, except as an adjunct to other people’s schemes or actions. No evidence remains of her own opinion of the career which was thrust upon her”. In other words, it’s anybody’s guess, and writers from Shakespeare onwards have been free to imagine her thoughts and feelings.

It’s now accepted that Shakespeare, in following the official Tudor version of history, blackened Richard’s name. The Richard III Society was founded to search for the truth and Josephine Tey’s novel The Daughter of Time, published in the 1950s, has probably been the most influential book on the subject. For both Gregory and Nickell, the real rotter is George, Duke of Clarence who betrays his brother Edward and imprisons Anne in order to control her inheritance. Clarence, condemned to die, in Gregory’s version chooses to be drowned in a butt of malmsey wine. I thought the butt of malmsey was just a story, made up years later, so could have easily have been omitted, but Gregory seems to need to find an explanation to counter Shakespeare’s famous scene.

There’s also a nod to Richard’s physical deformity, the hunched back signalling evil, which we have been told was invented by the chroniclers. In the TV series, when Richard and Anne go to bed for the first time, the camera lingers on his umblemished back. Gregory’s book was published before the recent discovery of Richard’s skeleton in Leicester which to everybody’s surprise showed that Richard did indeed have a severe curvature of the spine.

The real revelation of the series, though, is Margaret Beaufort. She doesn’t figure directly in Shakespeare’s plays, Queen Elizabeth referring to her “proud arrogance”. Stanley defends his wife:

I do beseech you, either not believe

The envious slanders of her false accusers,

Or if she be accus’d on true report,

Bear with her weakness, which I think proceeds

From wayward sickness, and no grounded malice.

But what a woman Gregory makes of the mother of the future Henry VII! Clever, devout, several-times married and used to being snubbed she will do anything to ensure her son inherits the crown. She tries to do what Shakespeare’s Richard III does, framing her “face to all occasions”. Like him in Henry VI Part 3, she does

but dream on sovereignty;

Like one that stands upon a promontory

And spies a far-off shore where he would tread,

Wishing his foot were equal with his eye;

And chides the sea, that sunders him from thence.

At the end of episode 7 her husband gives her the news that her son has been reinstated with his title, Earl of Richmond, but that his prospects of becoming King are slim. “Your Henry’s going to have to walk past five coffins to get to the throne and I don’t know how he’s going to manage that. Do you?” With Margaret’s serious face in close-up, then seen from above, she crosses herself and, staring at sea of burning candles, blows out the nearest one and the screen goes black.

I was reminded by the lines further on in that same speech of Richard’s,

And yet I know not how to get the crown,

For many lives stand between me and home:

And I, – like one lost in a thorny wood,…

Torment myself to catch the English crown:

And from that torment will I free myself,

Or hew my way out with a bloody axe.

Is Margaret Beaufort, I wonder, going to prove as ambitious and deceitful as Shakespeare’s Richard III?

Thank you for including Lesley’s ‘The White Queen’ in your blog. Such a shame that Gregory subsequently hijacked the title. I find I can only watch the tv series in company as I get too cross with the inaccuracies: not so much factual for, as you say, Shakespeare played fast and loose with the facts, but with the basic setting/costume errors, for which there is no excuse these days.

I agree with Mairi. However, from the BBC’s point of view they aren’t pitching to costume/architectural historians but to the general public- and if it encourages an interest in- and desire to learn about- history then surely this is more important? People can establish the details for themselves if their interest continues :).

Blackadder, for example, is astoundingly inaccurate in every possible way – but I am not ashamed to admit that, alongside Hever Castle and the raising of the Mary Rose, it helped to establish a childhood interest in English, European and particularly Tudor history which in time became a serious one

Televisual interpretations should not be dismissed so readily. After all, we do not know how many children will be inspired to pick up a history book, probably for the first time, because of programmes like ‘The White Queen’.