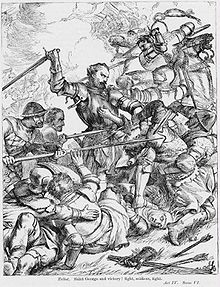

According to the messenger who gives the news in the first scene of Henry VI Part 1, Lord Talbot was captured by the French during a battle that took place on 10 August.

The tenth of August last this dreadful lord,

Retiring from the siege of Orleans,

Having full scarce six thousand in his troop.

By three and twenty thousand of the French

Was round encompassed and set upon….

More than three hours the fight continued;

Where valiant Talbot above human thought

Enacted wonders with his sword and lance:

Hundreds he sent to hell, and none durst stand him;

Here, there, and every where, enraged he flew:

The French exclaim’d, the devil was in arms;

All the whole army stood agazed on him:

His soldiers spying his undaunted spirit

A Talbot! a Talbot! cried out amain

And rush’d into the bowels of the battle.

And yet it is known that the battle of Patay, where Talbot was taken prisoner, took place on 18 June. Not only that, but the messenger bringing this news does so immediately following the funeral of Henry V, which happened in 1422, whereas the Battle was not until 1429. It’s another example of how Shakespeare changed events to suit himself, though it doesn’t explain why he changed the date and month. Was it just the fact that “The tenth of August” fits better in blank verse than “The eighteenth of June”?

It’s thought that Henry VI Part 1 was written after what we now know as Henry VI Parts 2 and 3, and Shakespeare certainly plotted it carefully in order to present the story that he wants to tell. Andrew Cairncross, in the Arden Shakespeare edition of the play describes how “he constantly inverts historical order, compresses, expands, repeats, anticipates, transfers events and characters, omits, invents imaginary scenes and characters, and all for dramatic purposes”.

The play tells how England lost its territories in France, and much of it pits the English military leader Lord Talbot, the Earl of Shrewsbury, against the “maid of France” Joan la Pucelle. Talbot is characterised as the last of the medieval heroes, an audacious soldier unswervingly loyal to his king while most of the English nobles are quarrelling amongst themselves, and Joan’s power is the result of witchcraft and lies.

Shakespeare used Edward Hall’s book The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Famelies of Lancastre and Yorke, published in 1548, as one of his sources. Describing his death, he writes of Talbot’s reputation:

At this battle … ended his life John Talbot … first earl of Shrewsbury, after that he with much fame, more glory, and most victory had for his prince and country, by the space of xxiiii years and more, valiantly made war, and served the king in the parts beyond the sea…. This man was to the French people, a very scourge and a daily terror, in so much that as his person was fearful, and terrible to his adversaries present: so his name and fame was spiteful and dreadful to the common people.

Shakespeare reorganises the facts with terrific panache. In the play, Talbot and his son die at the end of Act 4, Joan la Pucelle is condemned in Act 5 Scene 4, and the Duke of Suffolk is sent to France to fetch Margaret who is to marry Henry VI only in Act 5 Scene 5.

In fact Talbot and his son were killed in Castillon in 1453, Joan had been executed in 1431 and Suffolk fetched Margaret from France in 1445-6. Shakespeare’s close plotting, rearranging the events of history to create a clear sequence of events, made it one of his great early successes. And Talbot was a popular hero. Thomas Nashe, in Pierce Pennilesse, commented on the play in performance:

“How would it have joyed brave Talbot, the terror of the French, to think that after he had lain two hundred years in his tomb, he should triumph again on the stage and have his bones new embalmed with the tears of ten thousand spectators at least (and several times), who, in the tragedian that represents his person, imagine they behold him fresh bleeding.”

Talbot’s death seems to mark the end of the age of chivalry. Viewed like this, no wonder Shakespeare placed it before the taunting of Joan la Pucelle by the English lords and her attempts to save herself by lying . Amongst themselves, the nobles lament:

Have we not lost most part of all the towns,

By treason, falsehood, and by treachery,

Our great progenitors had conquered?

… I foresee with grief

The utter loss of all the realm of France.

A prediction which Shakespeare’s audiences had already seen fulfilled on stage, and which was also matched by historical fact.

Hi Sylvia. Thanks for this post. Have you seen the annotated edition of Halle’s Chronicles at Lancaster University? In the 1950’s, Keen and Lubbock analysed the annotations which correspond closely to Shakespeare’s use of the text. At least one uses language that occurs in Shakespeare but not in Hall (i.e. defacing the blood). We believe the handwriting is Sir Henry Neville’s. Perhaps nothing, but another annotation translates the standard English word “Comet” as “Cometa” – the Latin used (habitually) by scientists/astronomers. Sir Henry studied astronomy at Oxford under Henry Savile. Best wishes Bruce.

The lionisation of Talbot in Shakespeare may also be significant. When he was 9, he mother re-married Thomas Neville – Lord Furnivall – who was a major influence in his life. Talbot married Maude Neville. The date of 10 August may be a confusion with the date of the murder of his son, Sir Christoper , with a lance at the age of 23 by one of his own men, at Cawce, County Salop.

Thanks a lot. So much more to learn about English history and how it relates to Shakespeare’s plays. Always read these posts with avid interest.