I’ve just been enjoying Dr Jami Rogers’ new article The Shakespearean Glass Ceiling: the State of Colorblind Casting in Contemporary British Theatre, which appears in Shakespeare Bulletin Vol 31 no 3, pp 405-430. As well as providing a fascinating analysis of changes in the casting of black and Asian actors over the last 30 years, she considers how far we have come and how far there is still to go.

One of the starting points of her essay is the surprising statement by Mark Lawson, writing on the planning for the TV series The Hollow Crown, that “It’s also a relief to hear that next year’s BBC Shakespeare season, under the control of director Sam Mendes, will feature colorblind casting – now standard in the theatre”. She notes that this statement unintentionally gives weight to the status quo in which there are in fact “relatively few black, Asian or mixed-race actors in total…with even fewer attaining leading role status”, the glass ceiling of her title.

A complicating factor is that of definitions. What is meant by colorblind casting, integrated casting, or cross-casting, all terms widely used in this context? Rogers traces the ideal back to the American director Joe Papp, who in 1948 wrote that “In the best tradition of theater and democracy, there [should be] no discrimination against fellow human beings”. In Helen Epstein’s biography Joe Papp: an American life, Ellen Holly reported that talent should be “the sole casting criterion”, with “skin color…a completely irrelevant issue”.

The danger of Lawson’s comment is that it encourages complacency, and the Guardian’s Lyn Gardner was closer to the mark when she wrote in June “After all, only when black, east Asian and other minority actors get a crack at roles that weren’t written specifically for non-white actors, but which are just fantastically good parts, will we be able to celebrate the untapped talent and have a theatre that genuinely reflects the world we live in”.

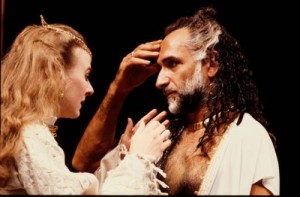

Othello is the most obvious role for a black or Asian actor in Shakespeare, and the last white actor to “black up” in Stratford-upon-Avon in this role was Donald Sinden in 1979. In 1989 the RSC felt the need to mark a change, with Willard White dubbed the RSC’s first black Othello. This could only be claimed because back in 1959 when Paul Robeson took the role the theatre was then called the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre. The awkwardness of the situation was signalled by,between Sinden and White, Ben Kingsley being cast. He’s half-Indian, and was rumoured to have been sent on holiday to boost his tan so he could play the role without additional make-up (though I have also heard that he did, perhaps as the tan faded). The fuss about Kingsley in 1985 may have been the deciding factor in the RSC’s decision never to cast anyone other than a black actor in the role.

As highlighted by Lyn Gardner, though, the issue is of black and Asian actors playing roles normally taken by white actors. In 2000-2001, Michael Boyd directed the Henry VI/Richard III cycle at the Swan Theatre with the first ever black English king, David Oyelowo as Henry VI, and another black actor playing Warwick. When the plays were revived in 2006-8 at the Courtyard Theatre, these two roles were again played by black actors, Chuk Iwuji playing the king. Instead of being true colorblind casting, it was clearly part of the director’s concept to cast non-white actors in these roles, though to give Boyd his due he succeeded in drawing attention to the issue.

Directors’ concepts can work in other ways. In 2012 Gregory Doran’s Julius Caesar defined itself by setting the play in East Africa, with a cast of black British actors. In the same year the RSC staged an all-Asian production of Much Ado About Nothing. Even though neither tackled the issue of colorblind casting as such these two productions proved that there is no shortage of black and Asian actors more than capable of taking on Shakespeare’s toughest roles.

Maybe it was the casting of these plays that, later in the year, got Gregory Doran in trouble when it came to the version of the Chinese play The Orphan of Zhao. Only three of the seventeen actors were of Asian descent, none of them the lead, and Chinese and South-East Asian actors and their representatives demanded an apology from the RSC. They in turn defended themselves by pointing out that some Asian actors had turned down roles in the production.

Racial stereotyping and the setting of quotas are more worrying issues, and in her essay Rogers notes the continuing trend for the requisite proportion of black members of the RSC to be routinely cast as servants or in subservient roles such as Patroclus in Troilus and Cressida and Lucetta in The Two Gentlemen of Verona.

For myself, I want to see excellent performances, not just of leading roles but of minor parts too. And for Shakespeare, that relates to speaking. The language is complex and requires clarity of delivery and understanding of meaning, but we still see and hear actors of all races who don’t manage to make themselves heard or understood. The black Julius Caesar was notable for being beautifully-spoken and completely audible even though all the actors adopted East-African accents. But perhaps I’d better keep off the subject of mumbling, at least for now.

At As You Like It at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre this week, I found myself examining not just the ethnic origins of the actors on stage, but also the audience. It would be refreshing to find that the audience is also 10-15% black and Asian, but in spite of Asian tourists being on the increase, theatre audiences remain overwhelmingly white. Pressure to increase the proportion of black and Asian actors rarely comes from the audience, normally originating within the theatrical professions. But maybe it’s time for audiences to put pressure on theatres to swing the balance.

Years ago – Spring 1989(?), I attended a discussion on colour-and gender blind casting at the Shakespeare Institute, part of the RSC Festival, I think – a black actress, I’m not sure of her name, bemoaned the fact that she’d never be cast as Ophelia, to which Simon Russell Beale responded, ‘Well, let’s face it, I’ll never be cast as Hamlet!’

You never know!

Best wishes.

Dear Liz

Thanks for your comment. Definitely time for a black Ophelia I’d say!

I know of two: Bill Alexander cast Rakie Ayola as Ophelia at the Birmingham Rep – I think that was in the production with Richard McCabe. Alexander seems to have cast her in major roles at the Rep. Here’s her CV: http://gordonandfrench.co.uk/artists-profile-stage.php?ArtistID=73

Nick Hytner cast Ruth Negga as Ophelia in Rory Kinnear’s Hamlet in 2010 as well. There may be others, but that’s all I’ve uncovered so far.

Thanks so much for this information!

Plus Gugu Mbatha-Raw in Jude Law’s Hamlet at the Donmar in 2009.