At the beginning of last week I started hearing rumours that a set of the four Shakespeare folios (complete works published in the seventeenth century) was to be sold. A spokesman from the Library attempted to justify the decision: “We already own other copies of the folios, and we want to raise money in order to be able to increase other areas of the historic collections”, and the Library’s Director, Christopher Pressler, explained that the folios were “essentially duplicates” of others in the Library.

The extreme reactions caused by this announcement caught the owners, the University of London’s Senate House Library, by surprise. High profile academic Sir Brian Vickers, a visiting professor at University College London declared “to sell them is an act of stupidity of the highest order. These are invaluable documents for research purposes.” and Sir Richard Eyre, former Director of the National theatre, said the sale would be “indefensible”. The Shakespeare bulletin board SHAKSPER featured the story several times, including a long letter from Professor Henry Woudhuysen written in response to a letter from Mr Pressler asking for support. An online petition was also launched.

By Friday the University had backtracked, Professor Sir Adrian Smith, the Vice-Chancellor of the University, admitting that the decision to cancel the sale was caused by the overwhelmingly bad publicity.

But why did this sale, not apparently so very different from previous ones, generate such a vitriolic reaction?

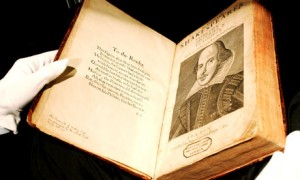

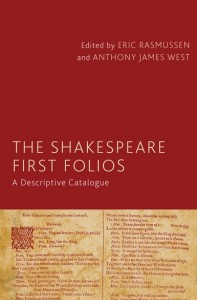

By describing them as essentially duplicates the Library seemed to be ignorant of the fact that each copy of the First Folio has been extensively documented in several censuses. Probably the most famous book in the English language, each one is different from the other 200 or so. In the case of the Durham Folio which was stolen in the 1990s then turned up at the Folger Shakespeare Library some ten years later, it was possible to prove which copy it was by using the information contained in one of the censuses even without its binding and pages containing obvious identification marks. First Folios are extreme examples as when they became desirable it became common to take sections from several damaged copies and combine them together to make a “complete” copy. But to an extent all early printed books show the same features, as individual pages were corrected during the printing process.

By describing them as essentially duplicates the Library seemed to be ignorant of the fact that each copy of the First Folio has been extensively documented in several censuses. Probably the most famous book in the English language, each one is different from the other 200 or so. In the case of the Durham Folio which was stolen in the 1990s then turned up at the Folger Shakespeare Library some ten years later, it was possible to prove which copy it was by using the information contained in one of the censuses even without its binding and pages containing obvious identification marks. First Folios are extreme examples as when they became desirable it became common to take sections from several damaged copies and combine them together to make a “complete” copy. But to an extent all early printed books show the same features, as individual pages were corrected during the printing process.

There was also the issue of the terms on which the University had been given the volumes. They form part of a massive bequest of several thousand volumes from philanthropist Sir Louis Sterling in the 1950s, His magnificent collection was intended to be seen as a fabulous addition to the University’s research collections as a whole, in perpetuity. As was quickly pointed out future donors are unlikely to give their treasured collections to organisations which decide to sell them off after only fifty years or so. The Arts Council made a statement to Channel 4 News: “It is of great importance that the public retain trust in museums, libraries and galleries to look after the collections held in their name. We are concerned that trust in these institutions may be undermined if disposals from collections are seen to be driven by financial considerations.”

Rationalising collections, that is removing items that are deemed irrelevant to the organisation caring for them, has become common. Taking care of collections is an expensive business, including many documentation processes, providing suitable storage conditions and ways of making them available to users, including digitisation. Moving a collection from a place where it is almost unknown to somewhere it will be frequently consulted is positive, but many rationalisations are made solely for financial reasons, as here.

A few years ago, in 2006, the Dr Williams Library, an independent theological library located in Bloomsbury, London, sold its copy of the First Folio. Their reason? Selling this iconic object, which was not strictly related to the rest of their collections, would raise enough money to ensure access to their core collections. It was a particularly fine copy that had been in the Library for many years. apart from a general sense of regret, I don’t remember any criticism in spite of a huge amount of pre-publicity.

Unlike Dr Williams library, Senate House Library, part of the University of London, one of the most important academic institutions in the UK, couldn’t claim the books were irrelevant. Indeed, this research library is expected to protect national heritage, of which the Shakespeare folios are probably the most obvious symbol.

We seem to have moved beyond the idea that the book is dead, that once something is available electronically nobody wants the physical item. Even modern novels are still being bought, given, kept and valued, and older books have a quality of their own.

This isn’t to say that Libraries aren’t having to change. Jerry Brotton, writing in the Guardian on 5 September, notes that the reason behind the Senate House decision is the crisis in Library funding. Students are able to access information and texts through the internet and research libraries are having to justify their existence. Ironically although students can’t access digitally the Folios which were to be sold they can compare several copies which have been digitised and he calls for Senate House to draw more attention to these unique volumes by digitising them to a high standard and providing an exhibition of the originals to celebrate the 2016 Quatercentenary of Shakespeare’s death. It could be that there’s no such thing as bad publicity after all.