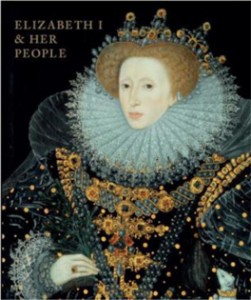

The new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, Elizabeth I and her people, puts on display a glorious collection of portraits of Elizabethans, supported by objects, manuscripts and books that provide some background to the world in which these people lived.

The new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, Elizabeth I and her people, puts on display a glorious collection of portraits of Elizabethans, supported by objects, manuscripts and books that provide some background to the world in which these people lived.

As well as famous paintings of Elizabeth and her courtiers, the publicity for the exhibition claims that “Visitors will also come face to face with lesser-known Elizabethans including butchers, goldsmiths, brewers, merchants, writers and artists”

Although, obviously, ordinary people were unlikely to be the main focus of portraits, I was hoping to glimpse some of these ordinary citizens. So I felt a little disappointed to find that most of the sitters for the paintings, if not actually noble by birth, came from a privileged background, and the paintings set out to celebrate the status and wealth of the sitter. At the end of the exhibition an original set of clothes worn for seafaring is displayed, alongside a statement that the labouring poor are rarely recorded. The plain, worn clothes are in stark contrast to the fabulous costumes worn by the sitters in the portraits.

Even in the painting of an unknown child and his nurse, although of lower social status than the gorgeously-dressed infant, the immaculate black costume and elaborate ruff show she is no common wet-nurse. Ordinary people also appear in the painting of the Fete at Bermondsey, where country people dance as the formal procession takes place. It’s still a genteel affair though, especially compared with the paintings of the Flemish artist Bruegel.

This is though no reason not to enjoy the exhibition, which does bring together paintings of less well-known representatives of the professional classes.

I particularly liked the painting of Edward Lister (1556-1620), whose painting is owned by the Royal College of Physicians. Here’s a link to some information about it. He held the post of physician-in-ordinary to both Elizabeth 1 and James 1, so he was no ordinary doctor. Coming from a family of distinguished physicians in Yorkshire he was educated at Eton and King’s College Cambridge. The portrait bears no obvious links to his profession, and Lister looks like a real person.

The same can’t be said of the portrait of a soldier, thought to be Cuthbert Vaughan (1519-1563), painted around 1560. This man with overflowing beard and stern gaze is surrounded by objects telling the viewer that he is a professional soldier, from the armour he wears to the plumed helmet and metal gauntlets, all beautifully decorated.

My favourite portrait in the exhibition, though, is that of George Gower (c1540-1596). It’s a self-portrait by the leading English portraitist of the day, dating from 1579.

A gentleman by birth, he was appointed Serjeant-Painter to Queen Elizabeth in 1581 and painted the Armada portrait of her. In the portrait he shows himself with brush and palette, the tools of his trade. What I found most endearing about the portrait, though, was his inscription and the image of a set of scales, balancing his coat of arms on one side and a compass, representing his skill on the other side. The point of both is that his skill outweighs the privileged status guaranteed by the accident of birth. This symbol is one that would have been appreciated by all those who succeeded in bettering themselves in the flourishing economic and cultural world of Elizabethan England, not least Shakespeare himself. There’s a review of the exhibition here, in Katherine Tyrrell’s Making a Mark blog.

I went straight from this exhibition to a performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Noel Coward Theatre, Shakespeare’s play in which ordinary people become the centre of attention. David Walliams (Bottom) and his friends are probably more the members of an amateur dramatics society than the collection of weavers, tailors, carpenters, tinkers and joiners that make up the “Hard-handed men that work in Athens here,/Which never laboured in their minds till now”, but as always, the performance of Pyramus and Thisbe is the highlight of the show, with Walliams revelling in the role of Pyramus. The “crew of patches, rude mechanicals /That work for bread upon Athenian stalls”, usually as invisible as the working classes in the portraits on show at the NPG, deserve their moment in the spotlight.