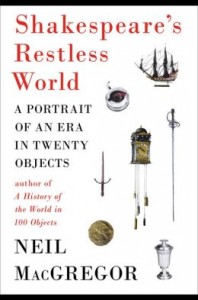

Most books on the subject of the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods include chapters on seafaring and exploration, religious change, war, medicine and government, supported by illustrations of maps, religious paintings, contemporary buildings, portraits and printed works. The head of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor takes a different approach in his book Shakespeare’s Restless World, which has just been published in the USA. UK residents had the chance in 2012 to hear MacGregor’s radio broadcasts, and to visit the BM’s Shakespeare exhibition, and it’s good to have a reason to revisit the book after the gap of a year.

Most books on the subject of the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods include chapters on seafaring and exploration, religious change, war, medicine and government, supported by illustrations of maps, religious paintings, contemporary buildings, portraits and printed works. The head of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor takes a different approach in his book Shakespeare’s Restless World, which has just been published in the USA. UK residents had the chance in 2012 to hear MacGregor’s radio broadcasts, and to visit the BM’s Shakespeare exhibition, and it’s good to have a reason to revisit the book after the gap of a year.

MacGregor follows the format of his hugely successful History of the World in 100 Objects. Each self-contained chapter effortlessly roams between the objects, the history of the period, Shakespeare’s works and our own world. The book is beautifully-illustrated, with images not just of the objects themselves but of other resources and of Shakespeare in performance.

The objects have been chosen carefully, and all are astonishing in their own way. Most are unfamiliar. Some, like the clock, the model of the ship and the Venetian goblet, are beautiful in their own right, made with tremendous skill. Others, like Dr Dee’s stone, are curiosities, or fantastic survivors like Henry V’s original funeral achievements. Some are gruesome, like the relic containing the eye of an executed Catholic priest, or commonplace, like the woollen cap that would have been worn every day by thousands of Elizabethan Londoners.

My favourite chapter is the one about the Pedlar’s Trunk, entitled Disguise and Deception. The object immediately reminds us of the trickster Autolycus in The Winter’s Tale, but on closer inspection the trunk turns out to be not what it seems. It was used as a cover by an itinerant Catholic priest, who would have been in constant danger of discovery:

…the linen, silk and damask in this particular pedlar’s trunk are not bits of material waiting to be transformed into smart clothes for a young Elizabethan woman. They have already been made into the illegal vestments of a clandestine Roman Catholic priest

The restless world portrayed in these pages is a long way from “Merrie England”. It’s a world of political and religious upheaval, where violence, uncertainty and fear were common.

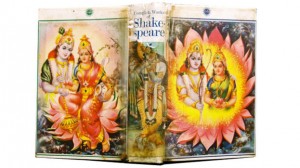

MacGregor also aims to make connections between Shakespeare’s world and our own, and to investigate the question of why Shakespeare has such a hold on not just the UK but the world. The book begins and ends with chapters that focus on these questions. Drake’s Circumnavigation Medal marked his round-the-world journey which began the story of the British Empire that reached its height in the nineteenth century when Shakespeare was our national hero and his works evidence of UK superiority. The final chapter, on the Robben Island Shakespeare, illustrates how truly international his influence has become.

As the quotation after which the book is named reminds us, Shakespeare’s plays are about experience, emotion and the search for meaning in life. In Measure for Measure, Claudio is condemned to die, and fears not dying, but death:

To be imprison’d in the viewless winds,

And blown with restless violence round about

The pendent world; or to be worse than worst

Of those that lawless and incertain thought

Imagine howling: ’tis too horrible!

The weariest and most loathed worldly life

That age, ache, penury and imprisonment

Can lay on nature is a paradise

To what we fear of death.

Claudio’s speech is only the second half of the discussion about life and death, though. It’s been started by the disguised Duke, who has visited him in prison and advised him to “be absolute for death”. But Claudio, a young man with everything to live for, fails to be convinced.

The book is subtitled “A portrait of an era in twenty objects”, and it tells many compelling stories about the period in which Shakespeare lived, and connects his plays with them. It is valid to ask how much physical objects can ever represent the concepts which Shakespeare wrote about, and some of the book’s reviews have been a little sniffy about making these links, but anyone interested in Shakespeare’s work and world will be surprised and intrigued by it. The book confirms the amazing way in which Shakespeare still shares with us his own restless search for meaning in life and death.