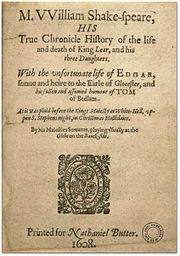

William Jaggard is well known as the printer of Shakespeare’s First Folio, along with his son Isaac. He was a member of the Stationers’ Company in London, but has got a name for unethical practices, at least in regard to Shakespeare. In 1599 he published The Passionate Pilgrim as a collection “by W Shakespeare” that turned out to be mostly not by Shakespeare, and in 1619 he co-produced the so-called Pavier quartos. These were reprints of existing quartos to which he gave earlier dates to get round the prohibition on printing plays belonging to the King’s Men. Plays treated in this way included A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Henry V and King Lear.

It’s perhaps surprising, then, that when it came to choosing a printer for the First Folio Jaggard was chosen. But he had printed a lot of large and expensive volumes such as the 1610 edition of Sir Thomas Elyot’s Castel of Health and the 1607 edition of Topsell’s History of Foure-footed beasts. It may also have been a factor that by the 1620s the business was mostly run by Isaac, William dying in 1623.

But he is not the only William Jaggard to play a part in the Shakespeare story. Captain William Jaggard came to live in Stratford in 1909, opening the Shakespeare Press, a bookshop and printing business, at 4 Sheep Street (unless the numbering has changed this is now the Vintner Restaurant). He had taken an active interest in Shakespeare and Stratford for many years, and when he moved to Stratford he had recently failed to become City Librarian of Liverpool.

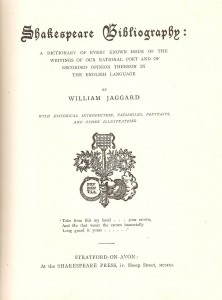

Jaggard’s great Shakespeare project was the compilation and printing of a Shakespeare Bibliography a massive volume published after over twenty years of effort in 1911. It is subtitled “A Dictionary of every known issue of the writings of our National Poet and of recorded opinion thereon in the English Language”.

The book has over 700 closely-printed pages, and in its flowery introduction Jaggard talks about the number of people whose work is recorded in the book. “Of the unnumberable myriads, over twenty-thousand workers held by his magic spell stand enunerated in this census”. He describes the action of lesser writers, who “gyrate, as a moth, round the flashing, dazzling arc of light known as William Shakespeare”.

Jaggard had already catalogued several collections of books, so it’s not surprising that he lists many of the earlier attempts to create bibliographies of books by and about Shakespeare. The catalogues of the Shakespeare Memorial Library, Birmingham, and the James Lenox Library in New York, are both mentioned, for instance. He notes that in 1889 Frederick Hawley, the Librarian at the Shakespeare Memorial Library in Stratford, aimed to create a “Catalogue of all the known editions of Shakespeare’s plays in every language”, but died before it could be completed.

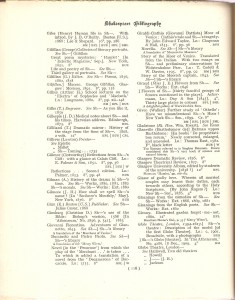

Jaggard’s book is not just a bibliography, that is a list of books, but aims to be almost a Shakespeare encyclopaedia. It includes illustrations, and some of the entries describe the relevance of the items included to Shakespeare. With entries crammed together it’s a difficult book to use, made more complicated because of the sheer number of additional cross-references he includes. But it’s these cross-references that make it useful. The book is in alphabetical order by author, but in the same sequence are subjects like music, with all the names of the relevant authors listed. When it comes to texts of Shakespeare’s plays, nearly 100 pages are taken up by editions of the Complete Works, and another 200 pages by editions of individual plays. These are in date order, and the names of all the editors are cross-referenced. Attempting to sort out the hundreds if not thousands of similar volumes without the ability to photograph and compare them must have been mind-bogglingly complicated.

Jaggard also included the locations of the books to which he referred. As well as the usual suspects (British Museum, and the specialised Shakespeare collections), are some less obvious ones like Melbourne Public Library in Australia and the State Library of Zurich, Switzerland. In 1911, of course, the Folger Shakespeare Library did not exist.

Jaggard triumphantly claims that “after twenty-two years’ effort, chiefly in time ill-spared from rest and recreation, I have at last reconciled aim with achievement, faith with fulfilment”. He must have known, though, that his aim of completeness was doomed to failure since even in 1911 the tide of new publications was relentless. The book is an extraordinary testament to Jaggard’s determination.

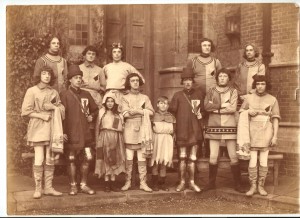

Captain Jaggard was a well-known figure, becoming involved in many local organisations. Among my late father’s extensive collection of Shakespeareana I recently found a photograph of a group of local walk-on actors, known as “supers”, for a visiting production of Everyman put on at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in the early 1920s. It features three members of the Jaggard family: Captain William Jaggard is in the back row, second from right, and in the front row first left is Aubrey who took over the running of his father’s business, and, second from right in the front row, Gerald Jaggard.

The book contains an inscription to the first William Jaggard: “to whom the world owes more than it deems for the safe preservation of an unparalleled literary heritage, the labour of a lifetime is gratefully dedicated”. Jaggard had investigated his family history, and liked to say that he was descended from the publisher of the First Folio, but it’s noticeable that he doesn’t make this claim in the Shakespeare Bibliography. Was he just being modest, or was he perhaps aware that his family history research might not be watertight? Either way, both William Jaggards deserve the gratitude of modern Shakespeareans.

That is such a wonderful photo of the “Supers” it is straight out of Black Adder!