2014 is quite rightly going to be dominated by the centenary of the outbreak of the first World War, but it’s also an important year for Shakespeare-lovers celebrating his 450th birthday. My ex-colleague Dr Susan Brock and I are currently co-writing a chapter on Celebrating Shakespeare in Stratford-upon-Avon for a book on Shakespeare celebrations worldwide.

We’ve been going back to contemporary reporting of the celebrations from the early 1800s. The organisation of the Birthday celebrations was one of the aims of the The Shakespearean Club when it was founded in 1824, in fact it’s often stated that the Club began them. It’s not quite as clear-cut as that: there were quite elaborate celebrations in 1816, the bicentenary of Shakespeare’s death. A commemorative medal was struck and on the day the town’s bells rang, cannon fired, there was a public breakfast, a dinner and ball and fireworks. It was regretted that they could not achieve a dramatic presentation, and promised something better.

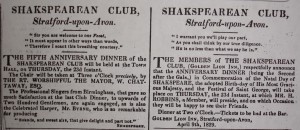

Much of the evidence that remains for the early years of the Club consists of printed materials and what was reported in the press: advertisements, accounts of dinners with lists of toasts, speeches and poems, and songs sung. It’s easy to get the impression that members had little real interest in Shakespeare. This is made worse by the well-documented rivalry between the original club and a second Shakespearean Club that appeared a couple of years later. Did this show admiration for Shakespeare, or for having fun? The advertisement for 1829 shows how intense the competition was, with almost identical offerings in the shape of dinners being provided by the landlords of public houses.

In 1830 local historian Captain James Saunders had had enough. He wrote “Cautionary Lines … to the belligerent Shakespeare Clubs engaged in preparing for the Celebration” and Mr Bisset urged “their glory should be to unite and be free to spread the Shakespearean flame”. The rivalry between the Clubs to outdo each other provided a focus to the detriment of the celebrations themselves.

Both clubs carried on, but by 1832 the original club was dominant again with 200 attending the dinner representing “nearly every respectable inhabitant of the town and neighbourhood”, and aimed to institute a library “bequeathing a permanent …collection of well-chosen books, to the inhabitants”. In 1833 the Warwickshire Advertiser devoted only 12 lines to the rivals who “enjoyed in the true spirit of hilarity”.

There are also hints that the Shakespeare Club was developing bigger ambitions. People from as far as London attended, and a more serious note is heard: “The worthy Mayor, Thomas Mills, Esq., [is] one who remembers the sacrilegious down-cutting and up-rooting of Shakespeare’s mulberry tree …and his younger fellow townsmen will need no exhortation from us to support him”. The mulberry tree had been cut down 77 years earlier, and the Club saw itself as a group of local people rightfully protecting their fellow townsman.

At the dinner in 1834 a Mr Serle, a visitor, exhorted members of the Club: “let all the memorials of Shakespeare contained in your church be repaired and preserved”. It was a fine aim in itself, but “Thus too would the Shakespearean Club acquire a still higher title to esteem, by exhibiting a religious care of the remains of him who. born in their town, and brought up among their forefathers, became the wonder of the world”.

Dr Connolly’s impassioned speech on the same day went further:

The ruin of Shakespeare’s house, that house in which he lived and died, the sacreligous destruction of his Mulberry tree, the loss of almost every personal relic of him; the defacement of his tomb, at the investigation of a selfish and conceited commentator; are all melancholy proofs that for a long time after his death there was either an indifference to his immortal memory, or the want of a Shakespearean Club to concentrate individual regard and give it an honourable utility. You cannot raise his mansion from the dust, nor restore the original colours of his monument, you cannot make the mulberry tree put forth its green leaves and crimson fruit once more, but his works, his unrivalled works remain… they flourish with a perpetual spring, and of their precious fruits men will gather to the end of time.

Stung into action, by 1835 the Shakespearean Monumental Committee had been set up to raise funds, led by Dr Connolly of the Club who suggested:

In case of a sufficient amount being subscribed the Committee would gladly extend their care to the preservation of the house in which Shakespeare’s father resided, in Henley Street, the presumed birthplace of Shakespeare, and to the house remaining at Shottery… and even to the purchase of the site of New Place… a spot which, being yet unencroached upon, they are most desirous of guarding from new erections and consecrating to the memory of him whose name has rendered it in the estimation, holy ground.

The first international contribution that I have yet found, was the First Annual Jubilee Oration, delivered in 1836 at the Chapel Lane Theatre by the American Tragedian, George Jones. During his two-hour oration he declared “Warwickshire in the 19th century has been rescued from the charge of an unnatural indifference”. He donated an American flag to the Club to be flown alongside the British flag at the birthday celebrations.

In 1837 the restored chancel in the church reopened on the Birthday. There was further talk about the need to preserve the Birthplace: “as long as it remains private property, we have no security against its total demolition”. The Stratford Club liked to see itself as the centre of both international and national interest, as in 1840 other clubs “cannot but feel that all these are the offspring of the Parent Club”. But even as it tried to broaden its influence it was in decline. There was a shift to London: towards the end of the decade the Birthplace was purchased for the nation with the assistance of committees fundraising in both Stratford and London. The creation of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in 1847 signalled the end of the Club’s status as the natural protector of the Shakespeare relics in the town. But it was the first such organisation, which inspired the creation of those that now dominate the town’s Shakespeare heritage.

The Shakespeare Club still exists with monthly lecture meetings being held at 7.45 at the Shakespeare Institute. These are the next few meetings:

14 January: Erica Whyman: Future plans for the RSC

11 February: Dr Erin Sullivan: Beyond Melancholy: Sadness and Selfhood in Renaissance England

11 March: Professor Jonothan Neelands: Learning Shakespeare by Heart not Off by Heart

8 April: Dr Nick Walton and Amanda Jenkins: Muse of Fire: A Shakespeare Entertainment