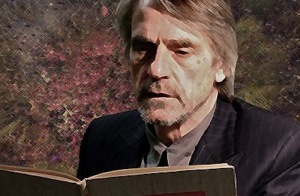

Listening to Jeremy Irons’ reading of T S Eliot’s Four Quartets on Radio 4 last weekend reminded me of the power of Eliot’s poetry. The Poetry Foundation’s website includes some information about the reading, and here is an article about Irons’ love for Eliot published to coincide with his reading of the Four Quartets at Hay Literary Festival in 2013. If you want to listen to Jeremy Irons almost hypnotic reading, this is the link, but you have only until Saturday 24 January.

I then realised that Irons and Eileen Atkins had also read and recorded Eliot’s The Waste Land. This is now available to listen to here. I remember being introduced to this poem while still at school, but reading it this year as we mark the start of the First World War the references to the post-war world are especially strong. I remember appreciating its sense of loss and the emptiness of modern life, but being a bit irritated by its inclusion of so many quotations from other poems that it needed pages of notes. In the introduction to the reading Jackie Kay explains how this, the first modernist poem, takes everything that has gone before, breaks it down and brings it back together. It’s only by looking back that Eliot is able to take a massive leap forward into the modern world.

Shakespeare, inevitably, is one of the poets that Eliot quotes in The Waste Land, as well as many others. You can’t miss that puzzling reference to Ophelia’s mad scene at the end of the session in the pub “Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night”, or the lines adapted from Antony and Cleopatra at the start of A Game of Chess:

The Chair she sat in, like a burnished throne,

Glowed on the marble,

before going on to describe a world so different from Cleopatra’s Egypt, “I think we are in Rats’ alley/ Where the dead men lost their bones”. He carries on this image of death later on, with a reference to The Tempest in The Fire Sermon:

On a winter evening round behind the gashouse

Musing upon the king my brother’s wreck

And on the king my father’s death before him.

White bodies naked on the low damp ground.

One of Eliot’s clearest references to Shakespeare is in his earlier poem The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock:

No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be;

Am an attendant lord, one that will do

To swell a progress, start a scene or two,

Advise the prince; no doubt, an easy tool,

Deferential, glad to be of use.

Eliot did not think Hamlet a success. In his essay on the play published in the 1922 collection The Sacred Wood: Essays on Poetry and Criticism, he wrote: “We must simply admit that here Shakespeare tackled a problem which proved too much for him. Why he attempted it at all is an insoluble puzzle; under compulsion of what experience he attempted to express the inexpressibly horrible, we cannot ever know. ”

Eliot instead praised the much less-highly regarded play Coriolanus. This article, considering the success of Ralph Fiennes film of the play, explains more and contains this quotation from Eliot:

“Coriolanus may be not as “interesting” as Hamlet, but it is, with Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare’s most assured artistic success. And probably more people have thought Hamlet a work of art because they found it interesting, than have found it interesting because it is a work of art. It is the Mona Lisa of literature.”

Eliot lived through both World Wars as an adult, dying only in 1965. It’s not surprising that he was drawn to Coriolanus, a play with much to say about flawed leadership, war, and its consequences. In his unfinished 1931 poem Coriolan Eliot follows a list of the glamorous trappings of Roman war, the flags, the trumpets, the eagles, with another list, of the hardware used to such devastating effect in World War I. Heartless bureaucracy is condemned by Eliot’s use of the repeated word, “mother”, spoken by Shakespeare’s Coriolanus when his resolve to destroy Rome cracks under his own mother’s emotional pleas for mercy.

A commission is appointed

For Public works, chiefly the question of rebuilding the fortifications.

A commission is appointed

To confer with a Volscian commission

About perpetual peace: the fletchers and javelin-makers and smiths

Have appointed a joint committee to protest against the reduction of orders.

Meanwhile the guards shake dice on the marches

And the frogs (O Mantuan) croak in the marshes.

Fireflies flare against the faint sheet lightning

What shall I cry?

Mother mother

Brilliant Sylvia.

Hi Sylvia,

Our Shakespeare Lovers group read “Coriolanus” a year ago – Jan. – Mar. 2013, here in the Washington, DC area.I loved the “tragedy” of the character – and we often talked of T.S. Eliot citing this play as one of his favorites. “Mother, Mother” he cried, when he finally submitted to her will. Except, it also tragically cost him his life. I put together some thoughts for you:

“There is a delicate scene – replete with the imagery of a “guilder butterfly,” where Coriolanus’s son’s rage is described by his wife’s friend, Valeria. Valeria had spent one afternoon, for a straight half an hour, watching the little boy chasing-and-releasing a golden butterfly. And then, most likely because of a fall, the next time he catches the butterfly he tears it to pieces – “how he mammocked it!”

Volumnia, Coriolanus’ mother, is proud to hear of this story of her grandson. The same Volumnia who created her warrior son, Coriolanus. The same Volumnia who would “rejoice” more at the sight of a man in the battlefield than that of one in her bed. Who loves evoking the images of blood and gore – preferring the image of Hector’s forehead split open and spilling blood, to that of Hecuba’s breasts suckling the baby Hector.

And suddenly, this same Volumnia, wants “peace” from her son? The son that she raised to proudly prefer “swords” to a “schoolmaster?”

The same son, who like his own son, has been raised to hate losing, or falling down? A son who sees the world only in terms of winners and losers, simply does not have the emotional range to be able to embrace the concept of peacemaking.

And then, there’s a moment of genius. His mother, failing to convince him, finally decides to kneel down before him, together with his wife and son and Valeria, their family friend. They all kneel before Coriolanus. And that’s when it happens…

Suddenly, they are speaking his language. Suddenly, someone is up and someone is down. It is simple. It is also “unnatural” in the reversal of order – having your own mother be on her knees and beg you for mercy.

But it works, and Coriolanus obliges. When Volumnia was pleading with him verbally, it did not work. The kneeling did the trick. Someone was up, someone was down. That was translatable in Coriolanus’s world… except that the “peace” he accepts to promote is unpalatable to his new comrades, and the tragedy that ensues is him getting killed for it in the end.

Tragic for the “mother,” too – for creating a man who could not step out of the win-lose narratives she has raised him on, and in the end, even though he submitted to her desires for “peace” – getting killed for it. Coriolanus never really changed. It wasn’t peace that he embraced, rather, the sight of his mother kneeling before him. And therein lies the tragedy for the man, and for his mother.”

Have so enjoyed reading your comments. It always interests me that, as you say, her words fail, but the gesture of submission by his dominant mother causes Coriolanus to crack. It says so much about their relationship up to that point.

It’s a great play – keep enjoying your Shakespeare!

Glad you like it and you put it in one sentence, very well… I’ll continue to tell members of your Blog too… ! Afsaneh