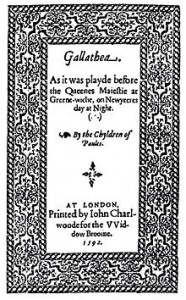

A new production of John Lyly’s play Galatea has just been announced. Performances of his plays are now a real rarity, but at his peak, in the 1580s, Lyly was the most fashionable dramatist in England. His plays were not aimed at the newly-opened popular open-air theatres such as The Theatre, but were intended for a more courtly audience at the indoor Blackfriars Theatre or at the Court itself.

There’s lots of information about Lyly on the SHALT website, including a video overview of Lyly’s place in the theatre, a performed extract from Sapho and Phao, and two interviews, with Andy Kesson and Lucy Munro.

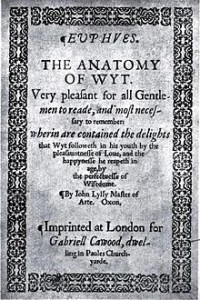

Lyly was about ten years older than Shakespeare, and his writing style greatly influenced him. His plays are mostly in prose, full of elaborate, sophisticated wordplay, and the style’s effect on Shakespeare can be best seen in the early comedy Love’s Labour’s Lost. Here Lyly’s love of using Greek myths as stories comes out in the staging in Shakespeare’s play of the Nine Worthies. The idea of the witty love contest, used by Shakespeare in The Taming of the Shrew and Much Ado About Nothing, can also be traced back to Lyly. In Love’s Labour’s Lost his influence can particularly be seen in the figure of Don Armado, and the pedantic discussions of Holofernes and Sir Nathaniel. Shakespeare both imitates it and takes the mickey. At the end of the scene between Holofernes and Sir Nathaniel, Constable Dull, representing the common man, claims not to have understood a word of their conversation. It’s easy to see why his plays haven’t stood the test of time, but it is great news that audiences will have the opportunity to see one performed.

Lyly’s plays were intended to be played by boy companies, and Lucy Munro points out that Shakespearean comedy begins to take over at just the time when the boy players ceased. Shakespeare took advantage of interest in their style while also inventing something of his own, in particular the cross-dressing of his heroines as boys in plays like As You Like It and Twelfth Night. Sexual confusion is also a feature of Lyly’s plays, in particular in Galatea. Here the unlikely story begins with the situation that the god Neptune has unleashed a devastating flood in retaliation for an offence against him, and since then has demanded the sacrifice of a fair virgin in exchange for peace. To avoid their daughters being sacrificed, two fathers disguise them as boys. Set loose in a forest, each girl (Galatea and Phillida) falls for the other who they think to be a boy. After a series of complications one of the girls is turned into a boy in order to bring about a happy end. For some reason the setting is in Lincolnshire. This may make sense when I see the play, but I can’t help thinking Shakespeare was right to set his comedies, at least nominally, in more exotic locations.

The parallels with Shakespeare are obvious: young people disguising themselves to avoid danger, falling in love with the wrong people, and needing supernatural intervention to make all well. And the idea that in order to make boys more plausible as girls you dress them as boys, was enthusiastically taken up by Shakespeare. This has a particular sexual dynamic in the modern theatre where women play their roles, but the new production of Galatea will feature a cast made up entirely of boys.

The new production is by Edward’s Boys, the schoolboy troupe from Shakespeare’s own school, directed by Perry Mills. Performance dates are:

13 March Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford

14 March Queen Mary’s Grammar School, Walsall

15-16 March Levi Fox Hall, King Edward VI School, Stratford-upon-Avon

25 April Playbox, The Dream Factory, Warwick

27 April Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, Shakespeare’s Globe, London

More information is available here.

The performance in London is particularly exciting because it will be the first performance in the Globe’s new indoor theatre of a play performed by a boy’s company, in the sort of conditions Lyly’s plays were written for. It is the culmination of a study day John Lyly and the Children’s Companies’ Repertoire. It promises to be a fascinating day including “public workshops and talks from actors, directors and leading Lyly scholars that will include Andy Kesson, Lucy Munro, Peter Saccio, Leah Scragg and James Wallace.”

Full information is available on the Globe’s website.

Ah, I don’t know Sylvia, I think there are a huge number of reasons Lyly doesn’t get performed as often nowadays, and not sure it’s anything to do with the plays themselves! When I last saw the Boys do a Lyly, I was stunned by how clear the language and plot were – I reckon they still stand up, especially in the hands of so wonderful a group of actors.

http://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/bardathon/2009/03/01/endymion-extracts-king-edward-vi-school-the-capital-centre/ .

Thanks for your comment, Pete. Having never seen a play by Lyly, or even read one in full, I’m hoping to be impressed. I’ve also heard from Perry, and I gather the boys are finding the language of the play very enjoyable and accessible. Can’t wait to see the play in March!