At least a couple of events relating Shakespeare and Italy are due to happen this year, one imminently in the UK and one, over the summer, in Italy itself.

I’ve already written about the summer school due to take place in the Italian city of Urbino from 12-26 July 2014 , but full booking details have now been released including timetabling and accommodation details.

James Stredder has just written about it for the newly-revamped British Shakespeare Association Education Network blog. His post is entitled A Summer school in Italy to inspire teachers, students and Shakespeare enthusiasts.

Here is part of the description of what’s happening during the course, which has an amazing line-up : it “will feature three leading Shakespearian directors and performers, Bill Alexander, Michael Pennington and Martin Best. The careers of each include many years of work with the Royal Shakespeare Company. Bill Alexander and Michael Pennington will lead work on ‘The Merchant of Venice’ and ‘Romeo and Juliet’, respectively, and Martin Best will perform his lecture-recital, ‘Shakespeare’s Music Hall’ – and teach a seminar on the Sonnets.”

The post itself explains what participants can expect to get from the school:

The Summer School brings together practitioners whose working lives have been devoted to performance, especially to realisation of the works of Shakespeare, in the theatre and in the concert hall. Their teaching sessions will focus on lively and creative approaches to Shakespearean texts (with the option for students of participating actively or of observing the ways in which performance evolves), but they will also set out to discover what part Italy and ‘the Italian context’ play in the appreciation and understanding of Shakespeare.

It should be a very special fortnight.

James’s post contains the idea that Italy held, and still holds, a special place in the minds of people from England. As far as we know, like most of his audiences, Shakespeare never travelled to Italy, but used it as a glamorous location for plays containing danger, violence, treachery and romance. In Cymbeline the innocent British man Posthumus is persuaded by the cunning, lying Italian Iachimo that Imogen has been unfaithful to him. She suggests “That drug-damn’d Italy hath out-craftied him”.

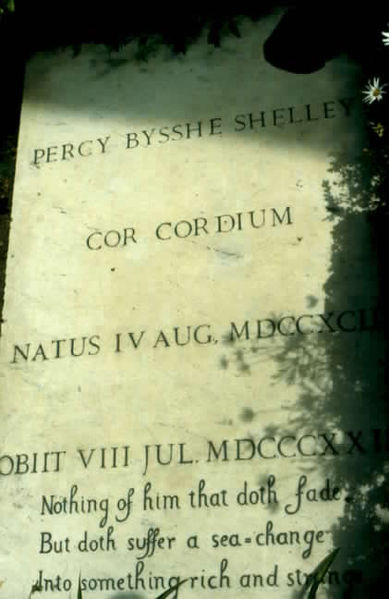

The country retained its risky reputation when in the early nineteenth century several young Romantic poets were attracted by the possibility of living more unconventionally than in England. Byron and Shelley spent several years in Italy and Keats travelled there in the hope of easing his tuberculosis. He died in Rome, both he and Shelley being buried in the same graveyard. Inevitably they admired Shakespeare’s writings about the country: several lines from The Tempest are carved on Shelley’s gravestone.

After Shakespeare’s time wealthy Brits became great travellers to the continent and particularly to Italy on the Grand Tour, an essential part of their education. Their search was for the foundations of European art and culture and tourists commissioned works of art with which to impress their visitors back home. In his anthology of almost a hundred accounts The Fatal Gift of Beauty: The Italies of British Travellers, M Pfister claims that these tourists, like Shakespeare, misrepresented the country:

The Italy perceived by the British travellers is – at the least – “half-created” by them. Or, to put it in less romantic and more fashionable terms: it is a construction, and “Italy made in England”.

This idea is being investigated in the one-day interdisciplinary conference being held at the University of Warwick this Saturday 22 February Italy Made in England: Contemporary British Perspectives on Italian Culture. Sadly for anyone who hasn’t reserved their place booking is now closed, but places are still available for the free screening of the documentary Girlfriend in a Coma at 4pm on Friday.

Quoting from the website: “Our proposal is to bring together scholars and specialists from a wide range of disciplines to answer the following critical questions:…How it Italy perceived within global culture, and indeed, how many and what kinds of Italies circulate today? This will span from the Renaissance image of Italy as a pinnacle of culture to the modern-day “sick man of Europe”.

In his Shakespeare, Politics and Italy blog, based around his book of the same title, Michael J Redmond agrees that the English perception of Italy tells us almost more about us than them.

Just like most of his contemporaries… Shakespeare was a voracious consumer of Italian books and English books about Italy. In many ways, the importance of Italy in every aspect of early modern English culture reflects the provincialism of that island, watching the intellectual ferment of the Renaissance from afar.

Italy’s a country that retains its fascination for those of us in the cold, damp islands of Britain.

I was quite surprised, astounded really, that Shakespeare was so familiar with legal procedures in Venice. Antonio signed a “unilaterale”, which Shakespeare translated as a ‘single bond’, meaning his signature and contract only, before a public clerk or notary, was sufficient and proper to encumber a debt. This did not occur in English law, only in the Roman Code. As a further commitment, he had to state and sign that he acknowleded the contract, so it could not later be denied as false. This did not occur in England either. Testimonial evidence about the contract did not apply, only the adversaries, another procedure unique to Venetian law. The Doge presided over the court, unlike a judge in England at the time. Foreigners were protected by Venetian law, due to the commerce it encouraged. Any Jew was such a foreigner, thus Shylock was protected and could appeal to the Doge in the middle of the night, and this occurs in Merchant of Venice. In brief, every procedure and instrumentality seems to have been preserved in amber in the play. Did the man who wrote the Shakespeare canon go to Italy? I don’t know. Does anybody have any suggestions? Was the lighting in the Boar’s Head Inn that good?

While Italy became idealized in the Renaissance period as the seat and source of high civilization, I do not believe that the trend should be encouraged to claim that English visitors were liars and dolts, and Shakespeare was one of those who couldn’t get Italy right. The facts and this play seem to line up extremely closely.

Thanks for your interesting comment. I’m no expert, but my copy of the play, published by the New Penguin Shakespeare and edited by Moelwyn Merchant, states “The whole legal structure of the play is, of course, fallacious. No system of law permits a man to place his own person in jeopardy, for a bond like Antonio’s is “against public policy” and “contrary to good morals”. A number of sources for the idea of the bond are mentioned, at least one being set in Italy, the point being that everyone would have known that the business of the bond was fictional.