The February 2014 meeting of the Stratford Shakespeare Club featured Dr Erin Sullivan, Lecturer and Fellow of the Shakespeare Institute, speaking on Beyond Melancholy – Sadness and Selfhood in Renaissance England. Even her title was a reminder of how much has changed in the description of health since Shakespeare’s time. The word “sad”, she told us, originally meant “gorged, full of food, replete”, and “selfhood” was probably not used at all.

Much of her talk was about the idea of melancholy as one of the four humours which were believed to determine the health of the human body. This theory, dating from ancient times, dominated Western medicine until only about 200 years ago, yet it has been almost completely forgotten.

The word “humour” was also used in Shakespeare’s period in relation to character (very obviously in Ben Jonson’s plays Every Man in his Humour and Every Man out of his Humour). Shakespeare uses the word many times: in sonnet 91 he writes “Every humour hath his adjunct pleasure,/ Wherein it finds a joy above the rest”. The word only developed its modern association with being funny in the late 17th century.

The word “humour” was also used in Shakespeare’s period in relation to character (very obviously in Ben Jonson’s plays Every Man in his Humour and Every Man out of his Humour). Shakespeare uses the word many times: in sonnet 91 he writes “Every humour hath his adjunct pleasure,/ Wherein it finds a joy above the rest”. The word only developed its modern association with being funny in the late 17th century.

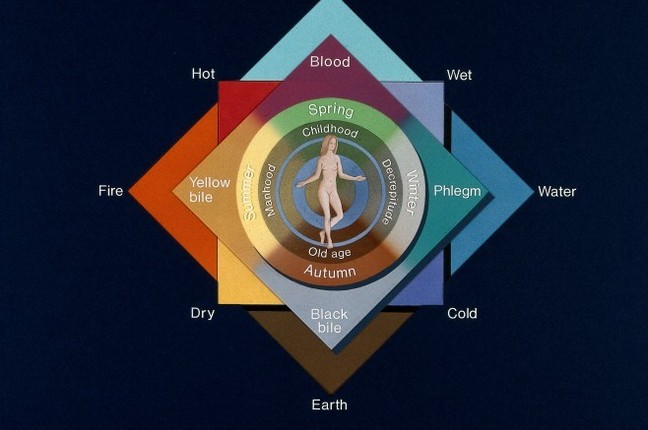

The four humours were blood, yellow bile, black bile (or melancholy) and phlegm. Each was linked with one of the four elements of earth, air, fire and water and two of the qualities hot, cold, wet and dry. A year or two ago the US National Library of Medicine created an exhibition on the subject, with an informative website. This page in particular gives more explanation, and some lovely images from the Folger Shakespeare Library.

This diagram admirably shows these connections and more: humours were associated with both the seasons and phases of life. The element “air” is missing from the diagram but should be at the very top. To be healthy the body had to be in balance, and illness was caused by having too much of one of the humours. Melancholy was linked with the element earth and the qualities of dryness and cold. It was also associated with autumn, and with old age. It was the most powerful of the humours, and could cause physical illnesses such as digestive problems, fits and lethargy. It’s easy for us today to think of melancholy as simply the mental illness known as depression, but the ancient theory of the humours is more sophisticated. The necessity of treating the whole person rather than just the obvious symptoms of a reported illness is an idea that is becoming more dominant again.

This diagram admirably shows these connections and more: humours were associated with both the seasons and phases of life. The element “air” is missing from the diagram but should be at the very top. To be healthy the body had to be in balance, and illness was caused by having too much of one of the humours. Melancholy was linked with the element earth and the qualities of dryness and cold. It was also associated with autumn, and with old age. It was the most powerful of the humours, and could cause physical illnesses such as digestive problems, fits and lethargy. It’s easy for us today to think of melancholy as simply the mental illness known as depression, but the ancient theory of the humours is more sophisticated. The necessity of treating the whole person rather than just the obvious symptoms of a reported illness is an idea that is becoming more dominant again.

I’ve been getting rather behind with the Shakespeare Institute’s MOOC on Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and have only just tackled week 3 in which Erin Sullivan talks about Hamlet’s melancholy and madness. If you’re not enrolled on the course it’s still possible to read her online article Melancholy, medicine and the Arts which was published in The Lancet Vol 372 issue 9642, in 2008.

Hamlet is Shakespeare’s most famous melancholic, memorably coming face to face with the reality of mortality when holding Yorick’s skull. Earlier, he analyses his own mental state:

I have of late, but wherefore I know not, lost all my mirth, forgone all custom of exercises: and indeed it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame the earth, seems to me a sterile promontory…. What a piece of work is a man … and yet to me, what is this quintessence of dust?”

Melancholy is also linked to introspection, thoughtfulness, and genius. No wonder it became so fashionable. Shakespeare’s characters Jaques in As You Like It and Don Armado in Love’s Labour’s Lost seem to affect it, rather than having it. Jaques doesn’t want to be thought of as having an ordinary kind of melancholy: “it is a melancholy of mine own”, he says, “in which my often rumination wraps me in a most humourless sadness”. Antonio in The Merchant of Venice, though, is a genuine sufferer, opening the play with the line “In sooth I know not why I am so sad”.

Erin Sullivan also mentioned that she had examined the casebooks of a number of doctors in Shakespeare’s period, including that of his son-in-law John Hall, and found that only about 5% of cases describe melancholy as opposed to grief or other kinds of sadness which had an obvious cause.

She also talked about the effect of the changes brought about by religion, in particular uncertainties of the time. Sadness could be caused by “godly sorrow”, the result of sin, and the idea that we can never grieve or repent enough. Despair, an extreme form of sadness, could be a result of the Calvinist idea that only the elect will be saved.

Towards the end of her talk she suggested that maybe in Shakespeare’s period misery was the dominant human condition. Did people expect to their lives to be dominated by suffering? Today we feel entitled to be happy. After all the Declaration of Independence in 1776 enshrined the right to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness”, though the Universal Declaration of Human Rights more moderately states “Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person”.

Shakespeare’s audiences may have expected their own lives to be full of suffering but they wanted to see on stage characters experiencing the extremes of sadness and joy. A potentially happy marriage or two usually ends the comedies, but anyone believing in the theory of the humours would have expected the extreme emotions of Romeo and Juliet to end in disaster.