This week Sir Antony Sher takes on the role of one of Shakespeare’s most famous characters, Sir John Falstaff, in the first of the Henry IV plays, for the RSC. It’s a role that has attracted many of the greatest actors of their day, in particular in the last seventy years or so, and it’s now seen as the key role within this pair of plays that say much about the state of England itself.

In the middle of the twentieth century Falstaff became the focus of attention in a series of productions and films of the Henry IV plays. One of the greatest was Ralph Richardson, who took the role for the Old Vic Theatre Company at London’s New Theatre in the autumn of 1945. It came during the second year of a three-year run at the New, dominated by an alliance between Laurence Olivier and Ralph Richardson, two of the most important actors of their time. While Richardson took Falstaff, Olivier played the heroic role of Hotspur in part 1 and the elderly, rambly Justice Shallow of part 2. The Shakespeare Institute in Stratford is celebrating these productions with an exhibition in their library that includes Olivier’s acting script for Hotspur, in which he made a few sketches of himself in the role. It’s a real treat to see this great item which will be on view until the end of March 2014. There’s a blog post with all the details here.

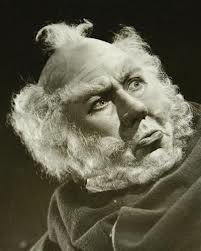

The Times suggested that Olivier had the “curious power of being at the centre of every picture”, but the greatest success of the productions was Richardson’s Falstaff. According to the Evening Standard, Richardson “made of Falstaff so much more than a mere buffoon, coward, liar and glutton that our hearts went out to him”, and went on “surely it is great acting when a man can win us to the cause of hypocrisy and align us against virtue”.

Years later, Peter Hall wrote a piece in the Guardian of 31 January 1996 on this production which he saw as a fifteen-year old. “The moment that gave me goose-bumps was the way Richardson did the Honour Speech. Although what he was saying was immoral he was desperately human. It was not a spectacular moment, just one of simple human realism: a bit soiled, a bit dirty and questionable – like life itself”.

A few years later, in Stratford, the Festival of Britain in 1951 was celebrated by a history cycle consisting of Richard II, both parts of Henry IV, and Henry V. The theatre was led by Anthony Quayle, who took the central part of Falstaff. Michael Redgrave played Richard II, Hotspur and the Chorus in Henry V, Harry Andrews played Bolingbroke in Richard II who becomes Henry IV, and rising star Richard Burton played Hal in both parts of Henry IV and Henry V. Quayle’s direction was a triumph, forcing critics to look afresh at some of Shakespeare’s best-known plays. Robert Speaight wrote “It is now possible to say that Shakespeare is better performed at Stratford than anywhere else in the world”.

According to The Times on 9 May, Anthony Quayle “deliberately presents a Falstaff who is scarcely likeable…There is always a shifty and calculating look in his eye”, though the News Chronicle on the same day was inclined to be indulgent: Quayle “has a mischievous twinkle in his roving old eye, a wicked old smile playing over his round mouth”. William Dobell’s painting of Quayle as Falstaff shows an unlikeable, disreputable, but vigorous man, unlike the cheerful, portly gent portrayed in the nineteenth-century painting at the top of the post.

Quayle himself felt that Falstaff was “a monster. he’s a desperate character and infinitely lovable”. And Richard David, in Shakespeare in the Theatre, suggests “As Falstaff, Anthony Quayle commanded the two absolutely essential qualities: a wholly winning gusto, and real, unpardonable wickedness”. Over two decades later Quayle played the part again in the BBC/Time Life versions of the plays. Seeing this, it’s tantalising to imagine how his younger self might have played it.

The third impressive interpretation of the role was Orson Welles, who was obsessed by the role for many years. He played it on stage in his own adapted versions before filming Chimes at Midnight which focuses on Falstaff and his relationship with Prince Hal. Filmed in 1964 it was released between 1965 and 1967. Welles had always downplayed the comedy in the role, and said the core of the film was “the betrayal of friendship”. For him, Falstaff was “the greatest conception of a good man, the most completely good man, in all of drama”.

Writing of the Richardson/Olivier production, in the immediate aftermath of the Second world war, the Sunday Graphic called the Henry IV plays “a great and terrific outpouring of the English spirit”. After seeing the Quayle productions, Kenneth Tynan wrote ” for me the two parts of Henry IV are the twin summits of Shakespeare’s achievement… great public plays in which a whole nation is under scrutiny and on trial”. And Orson Welles wrote of Chimes at Midnight: “the film was not intended as a lament for Falstaff, but for the death of Merrie England. Merrie England as a conception, a myth which has been very real to the English-speaking world… It is more than Falstaff who is dying. It’s the old England dying and betrayed”. Quite something for the new productions of Henry IV to live up to.

Just finished watching a DVD of the BBC’s The Hallow Crown with Simon Russell Beales as Falstaff- I think it was one of the most interesting portrayals of a Shakespearean character I have ever seen – a Falstaff that was frequently charming, but often odious – occasionally irritating and very human, but larger than life. I never thought I would say this, but in the “i know thee not old man” scene, Beale as Falstaff came across as quite moving – even in his attempts to “save face” near the end. His final expression spoke volumes.

And not surprisingly, the production values were fantastic – especially the color correction and grading (for example, a dull yellow tint at the scene of King Henry IV deceased in bed, and an impressive blue tint in palace interiors that really made the rooms look majestic, but cold) And last but not least, a gold tint in Henry V’s coronation scenes – not obvious effects, but enough to effectively heighten the mood

Thanks for this comment especially your notes about the effects of colour in this adaptation!