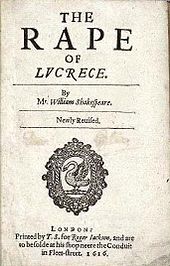

Exactly 420 years ago, on 9 May 1594, Shakespeare’s long poem The Rape of Lucrece was registered before being published later that year. In the dedication to the poem he had written the year before, Venus and Adonis, Shakespeare sounds somewhat apologetic at its lightweight tone: the poem focuses on the Goddess of Love’s steamy obsession with a beautiful youth. It’s known that it was a favourite of students. In the anonymous Parnassus plays, written and performed by the students of St John’s College Cambridge, the foolish Gullio says he will “worship sweet Master Shakespeare, and to honour him will lay his Venus and Adonis under my pillow” Perhaps the young Earl of Southampton, to whom it was dedicated, was not entirely happy with being associated with such a frivolous work. Maybe that is why Shakespeare vows ” to take advantage of all idle hours, till I have honoured you with some graver labour.”

This graver labour was The Rape of Lucrece, and although still sycophantic, Shakespeare in his dedication sounds more confident that he has hit the right tone. “The warrant I have of your honourable disposition, not the worth of my untutored lines, makes it assured of acceptance.”

Both poems were popular, going through several quarto editions. Both deal with uncontrollable physical desire. In both a powerful figure desires a subservient one, who subsequently dies. But the tone of the second poem is dark. A mature woman, married to an important man, is ravished and as a result takes her own life. This poem is one of Shakespeare’s least-read works nowadays, but it was highly regarded in its time. What was it about the poem that made it so admired?.

The story had inspired works of art such as Titian’s famous painting before Shakespeare’s time, and it stuck deep in Shakespeare’s imagination. Tarquin’s rape of Lucrece is almost re-played in his play Cymbeline, in the disturbingly voyeuristic scene where Iachimo hides in a trunk brought into Imogen’s chamber, and emerges to watch her as she sleeps. The story of the ravished Philomel, transformed into the nightingale in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, is referred to in both The Rape of Lucrece and in Titus Andronicus where another rape takes place. Macbeth refers to “Tarquin’s ravishing strides”. As so often Shakespeare uses closely-observed images from the natural world, here to liken Lucrece to a deer after she has taken the awful decision to kill herself:

As the poor frighted deer, that stands at gaze,

Wildly determining which way to fly,

Or one encompass’d with a winding maze,

That cannot tread the way out readily;

So with herself is she in mutiny,

To live or die which of the twain were better,

When life is shamed, and death reproach’s debtor.

The question of why the poem proved so popular may relate to passages like this but also to sections of the poem where Shakespeare moves away from the narrative to consider wider issues. Lucrece, having made her decision to commit suicide to preserve both her and her husband’s reputation, bemoans the unfairness of life. Here she blames time, and what he calls opportunity but which we might call chance, accident, or coincidence, which has made it possible for the rape to take place. Not Tarquin, but time, is held responsible for her situation. The subject of how our lives are shaped by forces beyond our control was indeed more likely to appeal to the serious reader. And the debate about personal responsibility versus fate is one which he went on to dramatise particularly in tragedies like King Lear and Macbeth.

Here is part of this section:

‘Mis-shapen Time, copesmate of ugly Night,

Swift subtle post, carrier of grisly care,

Eater of youth, false slave to false delight,

Base watch of woes, sin’s pack-horse, virtue’s snare;

Thou nursest all and murder’st all that are:

O, hear me then, injurious, shifting Time!

Be guilty of my death, since of my crime.

‘Why hath thy servant, Opportunity,

Betray’d the hours thou gavest me to repose,

Cancell’d my fortunes, and enchained me

To endless date of never-ending woes?

Time’s office is to fine the hate of foes;

To eat up errors by opinion bred,

Not spend the dowry of a lawful bed.

‘Time’s glory is to calm contending kings,

To unmask falsehood and bring truth to light,

To stamp the seal of time in aged things,

To wake the morn and sentinel the night,

To wrong the wronger till he render right,

To ruinate proud buildings with thy hours,

And smear with dust their glittering golden towers.

There is also the passage: “The aged man that coffers-up his gold/ Is plagu’d with cramps and gouts and painful fits;/ And scarce hath eyes his treasure to behold,/ But like still-pining Tantalus he sits, And useless barns the harvest of his wits;/ Having no other pleasure of his gain/ But torment that it cannot cure his pain.”

It is difficult to reconcile the author of this with the biographical record of the Stratford gentleman known as a miser and litigant for small sums.

At the time of the poem being registered Shakespeare had only just reached the age of 30, so even if he was writing autobiographically he was hardly aged.

There appears to be a completely different personality speaking from the page than that of a prudential grain-broker and money-lender who eventually, by relentless penury and usury, became the Stratford figure whose final recorded act was suing the local apothecary for a few pounds. I am afraid that the attempt to slice at a thread will not demolish the remaining fabric of reasoning. There is a complete disjunction of life and putative work.