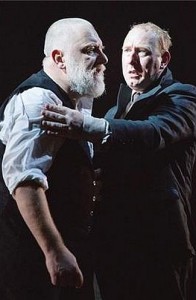

I’m finally getting to see Simon Russell Beale playing King Lear at the National Theatre this week. I’m not sure how much I’m going to agree with some of the interpretation, but with Beale you know, however difficult the play or unpleasant the character (I believe he doesn’t give us a likeable Lear), he will find the humanity and vulnerability in the part.

Lear’s trajectory takes him from the height of power and influence to the most wretched of states. King Lear is full of displaced people, from Lear himself, Gloucester, and most visibly, Edgar who uses the poverty of a beggar as a disguise. Lear, driven to madness, comes face to face with the plight of the poor and homeless when finding Edgar on the stormy heath.

Poor naked wretches, wheresoe’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your loop’d and window’d raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this! Take physic, pomp;

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou mayst shake the superflux to them

And show the heavens more just.

During Shakespeare’s own lifetime the condition of the poor was an important issue. An Act of Parliament passed in 1572 when Shakespeare was a child showed the general fear of unrest posed by people on the move. As a last resort vagrants, including masterless men and tinkers, could be executed, and begging was closely regulated. Even then though it was recognised that some poor people were legitimately moving around, such as harvest workers and those whose masters had died. The act recognised the need for compulsory contributions to help relieve poverty, but also allowed for the setting up of houses of correction and the appointment of local overseers of the poor. Levi Fox’s book The Borough Town of Stratford-upon-Avon describes how in Stratford the local corporation undertook periodic assessments of need, distributing coal money to the deserving poor and when necessary purchasing corn to sell on to them at low prices. Attempts were also made to find work for the unemployed.

In the 1590s a series of bad harvests caused the price of corn to rise dramatically. In London there were bread riots and uprisings driven by hunger in some parts of the country including Oxfordshire.

This led to new legislation in 1598 and 1601, replacing the brutal earlier laws with a more humane approach. In his book Poverty and Vagrancy in Tudor England, John Pound assesses the changes: “All the legislation reflects the action of a government cautiously groping its way towards a method that would at once remove the threat of insurrection and provide adequate care for all categories of poor”. Even so the first audiences of King Lear in the early years of the Jacobean period would have had a very different attitude to the destitute from ours today.

A couple of years ago Simon Russell Beale played another character who loses everything, Timon. When all his money is gone and debts are called in, his friends also desert him and he is driven to the brink of madness. He finds that he is “open, bare, for every storm that blows”. His servants remain sympathetic:

As we do turn our backs

From our companion thrown into his grave,

So his familiars to his buried fortunes

Slink all away, leave their false vows with him,

Like empty purses pick’d; and his poor self,

A dedicated beggar to the air,

With his disease of all-shunned poverty,

Walks like contempt, alone.

Though in a sense both Timon and Lear bring their own misfortune on themselves, what happens to them is a reminder that anybody can find themselves in need. In Timon of Athens Simon Russell Beale found himself rummaging through black plastic rubbish bags for food, a reference that could hardly have been clearer. Will this production of King Lear.also strike home at a time when caring for the needy, a fundamental part of a civilised society, is so obviously not working?

I recently heard that in the financial year 2013-2014 the Trussell Trust’s foodbanks had given three days emergency food to 913,318 people in crisis. Even more shocking was the news that in prosperous Stratford in 2013 well over 1000 people had received food from the local foodbank. I applaud the work of the Trussell Trust and other voluntary organisations, but am dismayed to find that we now live in a world where such organisations are necessary to ensure the most basic of human needs is met.