I recently wrote about how Shakespeare leaves gaps within the text which actors are able to fill using their own imaginations. I’ve been reading a book that describes how theatres themselves contributed to the writing and performance of plays, an extension of the idea that the author’s text is only one element of a play.

I recently wrote about how Shakespeare leaves gaps within the text which actors are able to fill using their own imaginations. I’ve been reading a book that describes how theatres themselves contributed to the writing and performance of plays, an extension of the idea that the author’s text is only one element of a play.

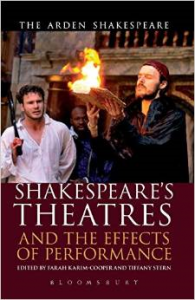

The 2013 book Shakespeare’s Theatres and the Effects of Performance, edited by Farah Karim-Cooper and Tiffany Stern and now available in paperback, looks at the theatres for which Shakespeare’s plays were written and how their features are represented in plays of the period. It owes much to the existence of the reconstructed Shakespeare’s Globe, which since its opening nearly 20 years ago has provided opportunities to examine the practicalities, as well as the symbolism, of the theatres themselves.

In the introduction the editors pose a number of questions for the essays to answer: “How did Elizabethan and Jacobean acting companies create their multi-faceted effects and how did this shape the plays written for them? What materials and technologies were available to early modern players, and how did these impact on staging? What role did the senses play in the reception of theatre and in what ways did texts acknowledge them? How was being the audience in the early modern theatre a multi-sensory experience, and where can that experience be traced in the plays that survive?”

Before the opening of Shakespeare’s Globe in the mid-1990s there were many debates about the shape and size of the original theatre, even the orientation of the stage. There was little hard evidence on which to build. In recent years archaeological digs in the built-up areas of central London have revealed fascinating details about the playhouses themselves. And the growth of interest in material culture has fuelled work on buildings and objects and their importance in cultural history. The work done in Shakespeare’s Globe has helped to emphasize the relationship between the plays in performance and the conditions for which they were written. In her chapter, Tiffany Stern observes “What is clear throughout Shakespeare’s writing is that, as is to be expected, he wrote for the places in which his plays were performed, sometimes wrapping their features into his fictional world, sometimes wrapping his fictions around their features.’ The book’s chapters are in three sections, the first on how the theatres themselves contributed to the experience; the second on the human body and how wounds, fights, executions, and disguises were represented, and the third examines the elusive experiencing of the five senses: the smells, acoustics, touch and taste, and spectacle bound up with the playhouses.

The connections between the plays and the buildings make these essays compelling. Without Shakespeare’s manuscripts, how are we to interpret the simple stage directions in the First Folio for the first scene of The Tempest? “A tempestuous noise of thunder and lightning heard. Enter a Ship-master, and a Boatswain”. Later in the scene there are directions for noises and at one point “Enter mariners wet”. Did these appear in Shakespeare’s manuscript, were they added to describe what had happened in performance, or were they an attempt to explain to readers the text that followed? I particularly enjoyed Gwilym Jones’ chapter Storm Effects in Shakespeare which looks at this question, comparing this scene with the storm in Julius Caesar, written for the outdoor theatres where fireworks were used more often than in the indoor Blackfriars for which Shakespeare imagined The Tempest. Nathalie Rivere de Carles’ chapter on curtains on the early modern stage closely scrutinises the multiplicity of uses, including symbolic ones, of these humble and usually-overlooked pieces of cloth.

In the second section Lucy Munro tackles the intriguing issues around the representation of blood and dismembered body parts. Her detailed survey answers questions about what was used, and how. It was, and still is, difficult to make scenes requiring false body parts convincing. Many of us will have seen modern productions that struggle: Imogen’s discovery of the decapitated body of Cloten, which she thinks to be her husband Posthumus, should be a moment of high emotion, but can easily turn to comedy. So can the appearance of dismembered heads in Shakespeare’s history plays, though the scene in Titus Andronicus in which Lavinia enters after her hands have been cut off is always shocking.

There is much more to enjoy in this book, and while it’s accepted that theatrical conditions affected writing, it’s frustrating not to know if playwrights were able to advance theatre design and technology. Not much is known about how the theatres developed between the building of the first permanent stage in 1576 and the closing of the theatres in 1642, nor how the plays were adapted for performance at court or at touring venues. Shakespeare must have been frustrated with the limitations of the theatre, that could not present the scenes as he imagined them.

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Maybe he hoped that in the future they would be fully represented on stage. They have certainly given countless artists and designers for stage and screen much to inspire them in the four centuries since he died.