Alan Howard, who died on 14 February 2015, came from a family of actors and writers, and following in the family tradition, became the most theatrical of actors. Many have concentrated on the partnership he developed with RSC director Terry Hands from 1975 to 1981. But before that Howard had worked with RSC directors Trevor Nunn and John Barton, and in 1970 he was chosen to play Oberon and Theseus in the production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream under the directorship of Peter Brook.

It was not at all obvious that Brook’s production would be successful. His rehearsal methods were experimental: “Always, an ever-finer form is waiting to be found through patient and sensitive trial and error… A concept is the result and comes at the end”. David Selbourne’s book The Making of A Midsummer Night’s Dream documented rehearsals, but the joyous energy of the stage performance seems to make few appearances in rehearsals.

For Brook, writing in 2013, “The life of a play begins and ends in the moment of performance. This is where author, actors and directors express all they have to say. If the event has a future, this can only lie in the memories of those who were present and who retained a trace in their hearts”. From this, you would think he kept no physical records of his work, but this seems not to be the case. In 2014 the Victoria and Albert Museum acquired Peter Brook’s personal archives, including his 1970 Dream, which had become the most influential and famous Shakespeare production of the second half of the twentieth century.

Evidence for how the production worked is to be found in the RSC archives at the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive. They are very full for the Dream: programmes from the different theatres it visited on its long tours, reviews, including many from abroad, many sets of photographs of both rehearsals and performances, several different prompt books from 1970-1972, technical scripts, production records, and sheet music. From these it’s possible to see how “Brook’s Dream”, evolved over its three-year history. Published books include a version of the prompt book and Selbourne’s rehearsal diary.

Other sources of information include accounts by actors: Sally Beauman, in her history of the Royal Shakespeare Company, quotes John Kane (Puck). Instead of making a play fit a concept, Brook “wanted the play to do things to them. You must act as a medium for the words…The words must be able to colour you”. Richard Moore has recently written about the production in Living to Please: A British Actor’s Life, available as an ebook.

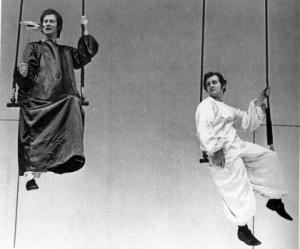

Moore played Starveling in the International Tour in 1972. Moore found Brook trying. He was “a parent that one could never please”. He provides details of the tour not found elsewhere, describing the endless technical rehearsals, and the dangers involved in such a physical show. He explains how in one venue Howard, on his trapeze, narrowly missed being dropped 18 feet to the stage floor He notes a charming detail: at the end of the curtain calls Howard closed each performance with “Goodnight. See you again. Sweet dreams” delivered in the language of whichever country they were in. The tour was gruelling, and took its toll both physically and psychologically. “How Alan coped, I’ll never know. He’d been playing Theseus/Oberon since the opening night in Stratford and was still giving wonderful performances and leading the company by example”. Since Howard’s death was announced I’ve read many tributes from actors and backstage workers, all affectionately praising him.

Howard never wrote memoirs, and in Coriolanus in Europe, another book about an Alan Howard tour, David Daniell reports a conversation with Howard that explains how he approached a role: “I don’t write about it. I act it”.

In the past two years John Wyver has managed the RSC’s Live from Stratford-upon-Avon broadcasts, so it’s interesting to find him writing in the Illuminations blog post referred to below, “Whisper it softly, but could it be that by transferring theatre to the screen we risk killing (with kindness) the very thing we love so much?”. To film or not to film (and how to film) has been a hot subject for years, but it’s hard to argue against relays to cinemas when they successfully take Shakespeare to people who would never see a live performance.

Decades ago, Alan Howard led massive tours around the world that massively enhanced the prestige of the RSC: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Henry V, Coriolanus. The 1972-3 tour of Dream performed 307 times in 31 cities to an estimated 450,000 people. These are impressive figures, but the effort was enormous compared with a live relay.

This extract from an educational programme, on YouTube, includes several clips.

Jan Pick’s website contains many links to articles and images of the Brook Dream.

No matter how ephemeral theatre is, directors, actors, designers and composers want to access the past. Audiences certainly want to remain connected to their memories. John Wyver trekked to the Aldwych in 1971 as a sixteen-year-old and still remembers: “I do want to bear witness” he says “that it was my cultural epiphany”.

In 2007 I attended the last performance at the RST before it was rebuilt. At the end the audience wandered around the stalls, looked up at the balcony, remembering, perhaps, their own epiphanies. When the theatre re-opened, the project “Ghosts in the walls”, projected images of past performances onto the old walls.

Ay, thou poor ghost, while memory holds a seat

In this distracted globe. Remember thee?

It isn’t merely sentimental to honour the past. If Shakespeare’s plays are capable of endless exploration and reinterpretation, then those who perform his plays, and the productions they appear in, are also worth recording and remembering. It would be tragic if Alan Howard, a giant of an actor, was not memorialised in the building he made his own.

This is a most beautiful article.

I saw a lot of Alan Howard’s acting !! The most thrilling was his “Coriolanus” (RSC-production with Terry Hands).

For me he was the best .

Gisela Lech

Thank you Gisela for your comments. I agree his Coriolanus was a fantastic achievement.

I saw one performance of AMNDream at Aldwych, then from the summer of 1975 saw just about everything Alan Howard did. Of course I loved all the history plays (and Trilogy Days were such memorable events in themselves) but few people have mentioned ‘Good’ or ‘Scenes from a Marriage’ – both intensely moving and both giving the lie to those who thought Alan was only a ‘barnstorming’ actor. I have yet to find another actor who so clearly communicates the sense of every line of Shakespeare and who lives the parts so naturally.

Thank you for your comment Lois. Alan Howard was capable of great sensitivity, often forgotten when concentrating on those histories and Coriolanus.

I was so saddened to hear of the passing of such an enigmatic performer. My first experience was his Richard III; the first time Shakespeare had made sense to me. The haunting playfulness he brought to the role was a revelation to a young under-graduate. A giant of a performance, yet at the stage door afterwards, I saw him leave wearing a flat-cap, glasses and a mac and carrying a plastic shopping bag…a stunning contrast. An unassuming individual who loved the art without asking for anything in return.