On Tuesday 8 September 2015 the new season of meetings of Stratford’s Shakespeare Club will begin. Following the AGM to be held at 7.15 the subject of the evening’s talk will be Shakespeare and Jewellery. It will be given by David Roberts, Executive Dean of Arts, Design and Media at Birmingham City University. Birmingham has been a centre of jewellery making for centuries with its own Jewellery Quarter. Dr Roberts will be examining Shakespeare’s references to jewellery and precious metals, and will also look at the developments in the industry during his lifetime.

Shakespeare often mentions rings and chains, and rings play a crucial part in some of his plays such as Twelfth Night and The Merchant of Venice. I’m sure it’s going to be a fascinating start to the season.

Maybe Dr Roberts will mention the gold seal ring rumoured to have been Shakespeare’s that was found in Stratford in 1810. While there’s no actual proof that it belonged to Shakespeare, the story has never been disproved, and the ring now receives serious attention. There is, however, another piece of jewellery which just might have belonged to Shakespeare.

This is a little brooch, and its history is some ways mirrors that of the ring. Like it, it was found by a poor workman, this time in 1828. Like it, the brooch was examined by antiquarians in Stratford and proclaimed to be genuine. The full story is told in leaflets that were published in 1883 and 1884, entitled The History of Shakespeare’s Brooch and A Lecture on Some Portraits of Shakespeare, and Shakespeare’s Brooch. Both were reprinted from newspapers.

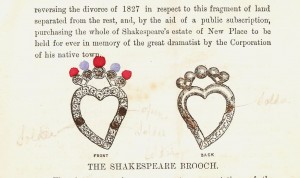

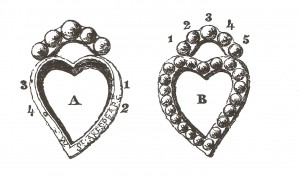

The man who found the brooch, Joseph Smith from Sheep Street, in 1864 made a statement on oath: “in the year one thousand eight hundred and twenty-eight I found the Brooch now shown to me, and having the name “W Shakespeare” engraved at the back thereof, upon a heap of rubbish brought out of, and laid in front of, New place, in Stratford-on-Avon aforesaid, during alterations being made in those premises. The said Brooch is made of silver, set with imitation stones, in the form of a harp (heart), with a wreath on top”.

Captain Saunders offered Smith £7, which he refused, having been told it was worth more, and already having it on show in his house. Saunders, convinced of the brooch’s authenticity, wrote a piece for the Mirror of Literature on 26 September 1829 including his own illustrations: “This brooch is considered by the most competent judges and antiquarians in and near Stratford, to have been the personal property of Shakespeare”. Robert Bell Wheler, Stratford’s other leading antiquarian, also tried unsuccessfully to acquire it. In the 1830s, as a result of his poverty, Smith lost possession of the brooch and it was shown at the Stratford Arms in Henley Street, another attraction for those visiting the Birthplace. While there, the brooch was broken and roughly soldered together which accounts for some of the differences between Saunders’ images and later ones. In 1864 the brooch was examined by a specialist of the South Kensington Museum, and by one of the most eminent firms of jewellers in Birmingham and London, who suggested the way the stones were cut was in the pre-Restoration fashion. “The brooch has every appearance of an antiquity bringing it at least as early as the time of Shakespeare”. The lettering was examined and claimed to be compatible with being of Shakespeare’s period, in particular the interlacing of the W and the way the H, A and K of the name are joined, a detail Saunders missed. If Saunders had been gullible, so were many other people. By 1883 John Rabone of Birmingham had acquired the brooch, and wrote both the pamphlets. The lecture contains additional information.

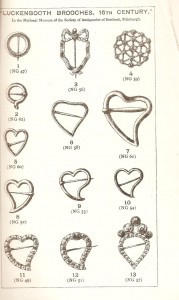

The Birmingham Natural History Society visited the Museum of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, in Edinburgh where they came across a display of “Luckenbooth brooches, 16th century”, mostly French, imported when relations between France and Scotland were close. Many, it was noted, are similar to Shakespeare’s brooch. Online information about Luckenbooth brooches is not very great. There is a page here, and to the National Museum of Scotland

Unhappily for those trying to make the case for the brooch, Luckenbooth brooches became popular love-tokens in Scotland just around the time this one was found, making it likelier to be dismissed. Rabone’s carefully-researched lecture, concluding that “it seemed beyond doubt that it was once Shakespeare’s, and was to be treasured with his signet ring as one of the very few of his personal belongings which have been preserved to us”, fell on deaf ears.

The brooch was also found at a time when relics, real or fake, were a source of local income, so the chances of it being fully authentic are remote indeed.

I first came across these pamphlets years ago among my father’s books, but heard no more until I recently searched the SBT’s website for items relevant to Shakespeare Club history. There was an entry for the brooch, with a photo, a relatively recent acquisition. The brooch is currently part of the Tudor Courtship display at Anne Hathaway’s Cottage. The caption, reading Heart-shaped brooch, made in the style of the 1500s: once thought to have belonged to William Shakespeare, but now believed to be a Luckenbooth brooch, conceals a complex story that could deserve further investigation.

One final thought: on the brooch, Shakespeare’s name is spelled as we would expect, but though Shakespeare himself used this spelling for The Rape of Lucrece, and it is used on the First Folio, this spelling has not always been used. In particular, at the time of the brooch’s discovery Shakspeare was the usual spelling. Might this lend weight to the idea that the brooch is earlier in date?