I wrote a few weeks ago about my visit to London’s Guildhall to attend the ceremony by which my niece was made a Freeman of the City of London. The best-known privilege to which Freemen are entitled is that of driving their sheep across London Bridge for free instead of paying a toll, a sight that must have reminded Shakespeare of his own involvement in farming. Assuming this “ancient right” was just a joke nowadays, we bought her a sheep puppet for her to carry over the bridge if she wished. But while at the Guildhall I picked up a glossy leaflet explaining the age-old tradition and how it is being reinterpreted. “In medieval times, sheep farmers drove their sheep across London Bridge into the City of London to sell them at market. Freemen of the City were excused the bridge toll that had to be paid by other people who were not Londoners, and “aliens” was the work used to describe people of other nationalities”.

I wrote a few weeks ago about my visit to London’s Guildhall to attend the ceremony by which my niece was made a Freeman of the City of London. The best-known privilege to which Freemen are entitled is that of driving their sheep across London Bridge for free instead of paying a toll, a sight that must have reminded Shakespeare of his own involvement in farming. Assuming this “ancient right” was just a joke nowadays, we bought her a sheep puppet for her to carry over the bridge if she wished. But while at the Guildhall I picked up a glossy leaflet explaining the age-old tradition and how it is being reinterpreted. “In medieval times, sheep farmers drove their sheep across London Bridge into the City of London to sell them at market. Freemen of the City were excused the bridge toll that had to be paid by other people who were not Londoners, and “aliens” was the work used to describe people of other nationalities”.

The driving of sheep to the City markets stopped many years ago, but in recent years the tradition has been ceremonially re-introduced. The modern bridge over which they new cross dates back to only 1973, replacing a nineteenth-century bridge. The one that Shakespeare knew was the famous medieval bridge with buildings along its entire length.

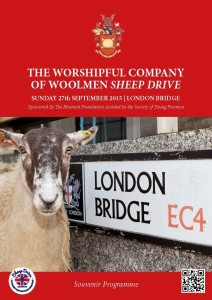

The Sheep Drive is now an organised fundraising event. In 2012 they got round the difficulties of using live animals by using stuffed sheep on wheels, but now a flock of sheep from Bedford, used to being herded, is brought in specially. As well as the sheep, it includes representatives of many of the livery companies in their regalia and large numbers of people dressed up in sheep-related costumes including Little Bo-Peep and the shepherds from the Nativity story. I wonder if anyone dresses up as the participants in the sheep-shearing feast from Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, or Phoebe, Corin and Silvius from As You Like It? If not, they should!

Shakespeare didn’t need any inspiration from Londoners to write shepherds into his plays. His father is best-known as a skilled glover, but early accounts suggested John Shakespeare was a wool-dealer and while alternations were taking place in the Birthplace, wool waste was found under the floor of the room known as “the Woolshop”. Michael Wood devotes several pages of his book In Search of Shakespeare to John Shakespeare’s business activities. Several decades ago a record was found dated 1569 showing that John was owed money by a man in Marlborough, Wiltshire, who had bought wool from him. Then two records showed that in 1572, John was charged with illegal wool dealing on a substantial scale. One deal took place near Stratford, but the other showed him dealing in wool at the Wool Staple in Westminster. “So we now know that the poet’s father was a brogger, a freelance wool dealer working illegally without the necessary licence from the London Wool Staple”. Wood imagines how John’s financial dealings might have started with skins for leather, later diversifying into wool. The Worshipful Company of Woolmen, which organises the Sheep Drive, like other livery companies aimed to prevent sharp practice and regulate trade. Shakespeare’s father seems to have been doing just the kind of deals they were trying to prevent.

In Medieval and Tudor England wool was a vital product. In the Cotswolds the wealth brought by wool to the area resulted in the building of the “wool churches”. One wealthy merchant engraved the following lines on the windows of his house “I praise God and ever shall – it is the sheep hath paid for all”. Taxes were raised for the government by the sale of wool, so they protected the industry. Elizabeth 1 made everyone wear on Sundays “a cap of wool knit and dressed in England”. The Worshipful Company of Woolmen set standard sizes for packages of wool to be sold just like the rules to protect consumers that regulated the size of loaves and their price.

Shakespeare certainly knew about the wool trade. In The Winter’s Tale the young shepherd tries to work out how much he would make by selling the fleeces shorn from his sheep: “Let me see – every ‘leven wether tods, every tod yields pound and odd shilling; fifteen hundred shorn, what comes the wool to? A tod was 28 lb, and it took the fleece of eleven sheep (wethers) to make a tod, worth twenty-one shillings. The answer to his calculation then is getting on for £200, a small fortune. Apparently Shakespeare gets these figures right. Even if his own father didn’t farm sheep there were many in the Stratford area who did. Adam Palmer was the neighbour of Mary Arden’s family in Wilmcote, and his 1584 inventory lists “wethers” among his many animals such as oxen, swine, horses, mares and poultry.

The next Great Annual Sheep Drive takes place on 25 September 2016. On payment of a £50 fee, Freemen can book a place to drive a sheep across London Bridge, after which they receive a personal certificate signed by the Lord Mayor to confirm they have exercised their rights. I’m very much hoping my niece will take advantage of this opportunity and will invite her Warwickshire relations to accompany her.