I wrote a week or so ago about Emma Smith’s new book The Making of Shakespeare’s First Folio, published by Bodleian Library Publishing, and the stories relating to the Bodleian Library’s own copy. One of the books I inherited from my father is another book about the Folio, R Crompton Rhodes’ Shakespeare’s First Folio, published in 1923 as a tercentenary tribute. My copy is inscribed with the name of my grandfather, W F Tompkins, Stratford-upon-Avon, July 1923. He had not long started working as the Guide at Shakespeare’s Birthplace after over 20 years at Holy Trinity Church, where one of his responsibilities was, again, guiding visitors. At the Birthplace, one of the SBT’s treasures was a copy of the First Folio, so I guess he was keen to learn all he could. The two books would seem to cover the same ground, but it’s been interesting to see how much the approach to this enigmatic volume has changed in the past 90 years or so.

I wrote a week or so ago about Emma Smith’s new book The Making of Shakespeare’s First Folio, published by Bodleian Library Publishing, and the stories relating to the Bodleian Library’s own copy. One of the books I inherited from my father is another book about the Folio, R Crompton Rhodes’ Shakespeare’s First Folio, published in 1923 as a tercentenary tribute. My copy is inscribed with the name of my grandfather, W F Tompkins, Stratford-upon-Avon, July 1923. He had not long started working as the Guide at Shakespeare’s Birthplace after over 20 years at Holy Trinity Church, where one of his responsibilities was, again, guiding visitors. At the Birthplace, one of the SBT’s treasures was a copy of the First Folio, so I guess he was keen to learn all he could. The two books would seem to cover the same ground, but it’s been interesting to see how much the approach to this enigmatic volume has changed in the past 90 years or so.

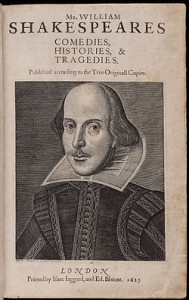

Rhodes approaches his subject with detective-like zeal, assessing evidence from a wide range of sources and coming up with a series of solutions. Studies of the First Folio were few, and copies of the original book were mostly still in private hands where they could not be accessed. In 1902 Sidney Lee had published a “reproduction in facsimile of the First Folio edition, 1623, from the Chatsworth copy in the possession of the Duke of Devonshire”, the same year he also published a Census of original copies. Emma Smith today knows that anyone with an internet connection can access several copies of the Folio online. Whereas Rhodes feels he must quote the whole of Heminges and Condell’s preface (well worth a read, incidentally), Smith can quote the highlights and leave her readers to look the rest up for themselves.

Rhodes transcribes other rare sources of information such as entries from the Stationer’s Registers and evidence from other writings of the period, valuable context for anyone interested in the period. In his judgements he exhibit a decisive confidence sometimes seen in the presenters of history documentaries on TV, but rarely employed by modern scholars. Writing about the authorship of Pericles, for instance, he states “Pericles was not Shakespeare’s”, giving a few reasons, and justifying its omission from the Folio. Smith, by contrast, reflects modern critical thinking by explaining the complexities of collaborative writing in the early modern theatre. She describes Pericles as a play “where Shakespeare’s part-authorship is not in doubt”. Where Rhodes presents us with evidence followed by definite conclusions, Smith poses questions. “Can we feel confident that Heminge and Condell actively excluded rather than mistakenly omitted Pericles and The Two Noble Kinsmen and perhaps other plays too, and if so what was their operative principle of selection?”. We obviously don’t know the answers, but being open to debate is no longer a sign of weakness.

I’m fond of Rhodes’ book, not least for the amount of raw information which he has gathered together and transcribed. Much of it must have been new for almost everyone coming to study Shakespeare’s plays. I enjoy his forthright opinions, and it’s fun to find he does occasionally admit defeat. Trying to work out whether the printers were working from Shakespeare’s own manuscripts or the theatre’s prompt books, is one such case. “The problem is, at least to me, insoluble”. Since Rhodes’ day many people have devoted years of their time to studying the differing texts of the Folio, and I’m sure there are still differences of opinion. Emma Smith is able to take advantage of this mass of modern academic research and, taking us by the hand guides us through conflicting evidence, letting us see how difficult it is to be as decisive now as Rhodes was. She’s not trying to find definitive answers, but, to quote the blurb, “telling the human, artistic, economic and technical stories of the birth of the First Folio”.

One of the most enjoyable sections of Emma Smith’s book is the section on an area that Rhodes did not look at in detail: the actual printing process. Perhaps he thought of printing as a merely mechanical process, while he was trying to work out more intellectual questions: the complex relationships between the acting companies and the printers, the issues of who owned which copies and the right to print them. For us, used to printing at the press of a button, hand-printing and the work of a print shop are both completely foreign and fascinating. And without knowing how printing and book publishing worked it’s almost impossible to understand how many of the idiosyncrasies of the First Folio came about. Smith explains carefully and clearly the whole business of setting, proofing, printing and binding. She calls the publication of the Folio in November 1623 “the end of a protracted process, and of a period of considerable effort by its many makers. It is the product of a number of very specific social, cultural and commercial contexts, and of numerous individuals with different skills and different agendas.”

Many of the mysteries that perplexed Rhodes are still not completely solved, but Emma Smith’s admirable book provides us with many of the answers and guides us through the complex web of events and relationships that together created Shakespeare’s First Folio.

I was amazed, as you say, at the ‘number of very specific social, cultural and commercial contexts, and of numerous individuals with different skills and different agendas’ involved – in my case when I published a modern eBook of poetry and illustrations. So I think the art and the skill remains, whatever the form of the ‘book’ – in print or pixels!