With the sudden death of Michael Bogdanov this week theatre directors and their importance in the staging of Shakespeare’s plays have been on my mind in the build up to Shakespeare’s birthday. Shakespeare was the first director of his own plays: he above all people must have known how he wanted roles to be played, and how scenes were to be staged. Given Hamlet’s advice to the players, “Let those that play your clowns speak no more than is set down for them”, we might assume he didn’t appreciate adlibs from his comics, but Shakespeare also gave actors space within the plays giving them choices to make about movement, gesture, emphasis, breathing.

From what I’ve heard about Michael Bogdanov he allowed his actors to be creative and even anarchic. The first scene I saw that was directed by him was in the John Barton production of Measure for Measure in 1970. While Barton took the serious scenes between Angelo, Isabella, and the Duke, he gave Bogdanov, his Assistant Director, the job of setting the scene in the prison. The character Pompey, who has previously worked in a brothel, is given the job of assisting the executioner Abhorson. This scene, in the prison, at night, was played as a riotously funny number, a major shift in mood from the serious discussion of power and corruption to the black comedy of a discussion about execution. Yet on the page there is hardly anything there at all. It was the first time I’d been aware of those spaces that actors can fill with life.

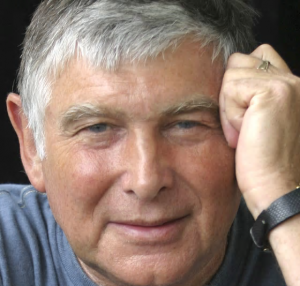

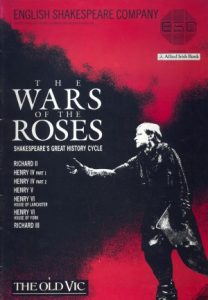

I became a fan of his work having seen three Shakespeares at the Young Vic followed by The Taming of the Shrew in 1978/9 at the RSC. At the RSC he worked with actor Michael Pennington on The Shadow of a Gunman, a partnership that led in 1986 to the pair forming the English Shakespeare Company. This was at least partly born out of frustration with the RSC for whom Bogdanov had only just directed a modern and controversial Romeo and Juliet (the one with an Alfa Romeo). The ESC’s greatest achievement, though not the only one, was a touring seven-play cycle of Shakespeare’s history plays The Wars of the Roses. You can hear him speaking himself in 1987, as his company began to define itself, in his Desert Island Discs interview. This week his publicist described his Shakespeare productions as “political, accessible, joyous and transformative”.

A WINTER’S TALE by Shakespeare, , Writer – William Shakespeare, Director –

Declan Donnellan, Designer –

Nick Ormerod

, Cheeck by Jowl, 2015, Credit: Johan Persson/

I was reminded of Bodganov’s approach when watching Cheek by Jowl’s live-streamed production of The Winter’s Tale. I admired so much of it: the modern, clear and uncluttered trajectory of the first half of the play, the physicality of the performances, the inventive set and lighting, and the energy of it. The production seemed less sure of itself in the second half, coming up with a number of parallels for Bohemia that reminded me only what an unpleasant and violent world we live in. Autolycus as the Jeremy Kyle type host of a chat show for unhappy people was at least funny, but Shakespeare’s conman uses nothing more violent than threats to extort bribes: here Autolycus changed into a border guard who viciously beat up a traveller for failing to supply documentation. Was this meant to make a point about the normalisation of violence? In just a couple of minutes I felt alienated from a production I had wanted to love, by a director, Declan Donnellan, I’ve always admired. It’s still a production very much worth watching, skilfully filmed from a live performance, and is available until 7 May 2017.

We’ve also been hearing more about the troubled Artistic Directorship of Shakespeare’s Globe in London. The outgoing Artistic Director, Emma Rice and her predecessor Dominic Dromgoole have both written open letters to whoever will be the new appointee, expressing their opinions of the job of being Artistic Director, and pointing out the shortcomings of the process at the Globe. Both insist that the Artistic Director must be allowed a free hand in the creative running of their theatres. The letters are written more in sorrow than in anger, talking with passion about the great opportunity of running this theatre, while warning the new Artistic Director about obstacles placed in their way by the Board. It will need to be a brave person who steps into Rice’s shoes, knowing what a difficult time she has had. But all credit to the Globe for publishing these critical letters on their website.

Bringing Shakespeare’s plays to the stage has probably never been easy: the man himself may have had frank discussions with his fellow-shareholders about what he wrote, and he probably argued that he needed a free hand too.