On Tuesday 4 April I addressed the pupils of King Edward VI School in Stratford-upon-Avon, Shakespeare’s School, at their morning assembly, part of our efforts to publicise the town’s two hundred-year old Shakespeare Club. The school has been in existence much longer than the Club, of course, but there are points of connection especially relating to the celebration of Shakespeare’s birthday. To the Headmaster of the School we owe the idea of the floral procession from the town to Shakespeare’s grave. The tradition began in 1893 with a single floral wreath, and quickly became a popular offering of humble springtime flowers open to anyone. It was only when this ritual became so popular the church could not accommodate everybody that the Shakespeare Club stepped in, setting a time and place for the start of the parade, requesting that all should bring flowers, and providing other entertainments during the day. Within a few years the Celebrations had become an international event.

There is another connection: at least one former pupil of the school, Charles Frederick Green, was one of the founders of the Club in 1824. Green, the son of a hatter, came from the same social class as Shakespeare, and was an avid admirer. His aim in helping to create and promote the Club was to “create an enthusiasm amongst the associates of [his] youth” for the memorials of Shakespeare in the town and the plays. In 2016, after the completion of a restoration project, the school has opened the room in which Shakespeare was a pupil and the Guild Hall where it is thought he saw his first plays. The pupils of the school are now involved in telling the story of Shakespeare’s education, and if Charles Frederick Green was alive today he would certainly be taking part.

Green writes about his enthusiasm for Shakespeare in the introduction to his book on the legend of Shakespeare’s Crab Tree, and gives the impression that he enjoyed his school days. Perhaps by the early 1800s there was less emphasis on rote learning, and less discipline, than there had been in Shakespeare’s time. Shakespeare always comments on how much schoolboys disliked school: from As You Like It, “the whining schoolboy, with his satchel/And shining morning face, creeping like snail/Unwillingly to school” to Romeo for whom “Love goes toward love, as schoolboys from their books,/ But love from love, toward school with heavy looks”.

The conversation of the Schoolmaster Holofernes and curate Sir Nathaniel in Love’s Labour’s Lost is dull and pedantic, though Shakespeare fills it with wordplay which his audience would have enjoyed. And in The Merry Wives of Windsor a boy called William is quizzed by his schoolmaster Sir Hugh Evans on his Latin. Here’s part of it, missing out the comic misunderstandings of Mistress Quickly.

Sir Hugh. William, how many numbers is in nouns?

William. Two.

Sir Hugh. What is “fair”, William?

William. Pulcher.

Sir Hugh. What is “lapis”, William?

William. A stone.

Sir Hugh. And what is “a stone”, William?

William. A pebble.

Sir Hugh. No, it is “lapis”: I pray you, remember in your prain.

William. Lapis.

Sir Hugh. That is a good William. What is he, William, that does lend articles?

William. Articles are borrowed of the pronoun, and be thus declined, Singulariter, nominative, hic, haec, hoc.

Sir Hugh. Nominativo, hig, hag, hog; pray you, mark: genitivo, hujus. Well, what is your accusative case?

William. Accusativo, hinc.

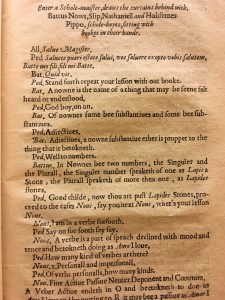

I hadn’t realised, until reading tweets from Jose A Perez Diez, how closely this parody of a Latin lesson is matched by one in John Marston’s play What You Will, probably written a year or so earlier than Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night (subtitled What You Will). Diez is working on the new critical edition of the complete works of Marston, due to be published by OUP in 2020. In this play, written for a company of boys, the schoolmaster appears before a class who greet him in Latin. One of them is then asked to “Stand forth repeat your lesson with out booke”. He says ““In nownes bee two numbers, the singuler and the plurall, the singuler number speaketh of one as Lapis a stone, the plural speaketh of more then one, as Lapides stones.”, and carries on to talk about figures of speech including nouns, adjectives and verbs, and their declensions. Much of this is apparently based on William Lily’s Short Introduction to Grammar, the standard Latin text book in use in schools.

Diez seems to be correct in noting that, judging by the evidence, many English dramatists hated learning Latin as schoolboys. If you want to get a flavour of what it was like to be a schoolboy in Shakespeare’s time, go along to Shakespeare’s Schoolroom where you will find out more.